The Vietnam War Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., stands out from the structures surrounding it, but not because it stands out. This monument is not very monumental at all. While the World War II Memorial lies in the center of the Mall, with complex fountains and wreathed pillars representing the fifty states, the Vietnam War Memorial is a singular, long, black wall built into the ground, bearing the names of the war's dead. There is no victory being celebrated, no commemoration of defended freedom, but a simple display of respect to those who gave their lives for a country's broken call.

The Vietnam War was hugely controversial, with much of America in opposition to it. American men were fighting and dying to "stop the spread of communism," but to many Americans, we were losing thousands upon thousands of American lives to protect a country we had no business protecting (Ankony). The war was also rampant with drug abuse, a problem that greatly affected it veterans. There were no systems in place to help Vietnam Veterans like there were after World War II, and many returned to a place with an antiwar counterculture that would even go as far as to harass veterans. These vets often ended up homeless in dire conditions (Ankony). Why would we, as a nation, build a memorial for this? The answer is simple. American soldiers gave their lives for their country. No matter what the context was surrounding the war, some brave men gave the ultimate sacrifice and deserve to be remembered for it. Maya Lin, as an undergraduate student, understood this perfectly when she submitted her "nihilistic slab of stone," as it was called by James Webb, a decorated Vietnam veteran and politician (Wills),[1] to a blind design contest in 1981. After it was announced that her design had won the contest, it immediately received strong opposition from many, including James Webb. Despite this opposition from high places, Lin held firm with her design.

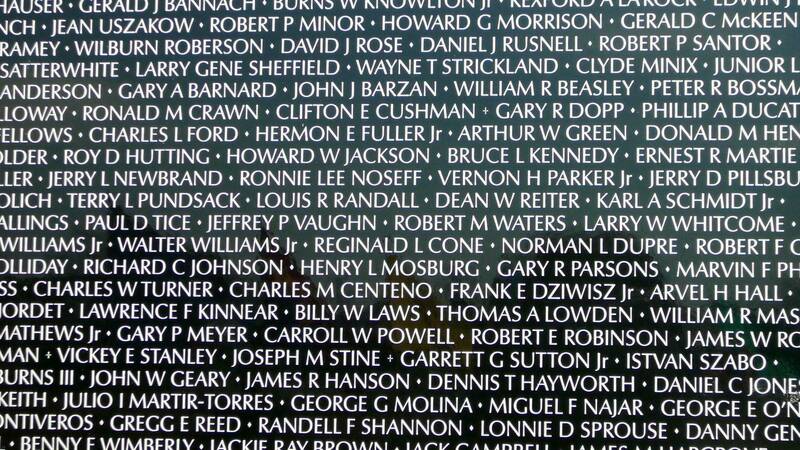

The structure of Lin's design shows America's general dislike of the Vietnam War, inherently and through contrast with other memorials. The wall was not constructed on a hill for all to see, nor was it built even as a freestanding wall. Lin designed it to be built into the ground, like a common retaining wall one would see in a suburban backyard, making it very insignificant compared to the Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, and World War II Memorial that surround it. All three of these monuments are in the center of the Mall while the Vietnam Memorial is off to the north side, out of a tourist's typical DC picture. The contrast between the Vietnam and WWII Memorials is the most telling. The WWII Memorial has an elaborate structure that seems to glorify the war. It celebrates our victory over Fascism, the Japanese imperialistic expansion, and the Holocaust, making anyone who walks around it feel proud to be an American; the Vietnam Memorial, on the other hand, has a quite different effect. When one walks down that black wall, reading the names of those who sacrificed themselves for a battle against another ideology that we did not win in Vietnam, one feels a wave of sadness sap the excitement out of a day at the monuments. The simplicity of the structure gives it its power, power that can be seen at the memorial everyday through the tears shed by veterans taking in their fallen brother's name. Its lack of ornament gives it a solemn feel that facilitates reflection on those we have lost and the monumental sacrifice they made. It does not glorify war, but pressures one to ponder why we were even in Vietnam and why those men had to die.

It's hard to drive through downtown Washington, D.C., without passing an old man with a scraggly beard and camo jacket holding a brown cardboard sign with something like "Homeless. Vietnam Vet. Please Help. God Bless" written on it in black Sharpie. After World War II, new systems like the G.I. Bill, which provided veterans with money for education, home loans, health care, and unemployment benefits, were put in place to help the veterans, and hiring vets was highly encouraged; but apparently we forgot about this after the Vietnam War. There was not very much change in these veteran benefit programs to account for the differences between the two wars in what the vets experienced while in combat and in the society they were coming back home to. Maya Lin's memorial design recognizes this in its color scheme. The wall is black the whole way down, representing the war and how it was a dark time for those involved, but the names of the ones who were lost are white. This shows how they are the ones meant to be remembered. It shows the veterans that the war they fought was not being memorialized; rather their fallen comrades and themselves by extension. The white names create a feeling of solidarity among those who were lost in that they are being remembered together as the light in a time of darkness, and because every name is the same color, that light is to include all veterans whether they are senators or men begging on a street corner.

While the majority of details on the memorial give an anti-war perspective, there is one subtle detail that cannot be ignored. The memorial is in the shape of a wide "V." This wide "V" is positioned so that one leg points at the Lincoln Memorial and the other at the Washington Monument. This addresses the complexity that is war. Even though there is the certainty that white names will always be casualties of war, when it comes down to it, war is often a necessary evil to protect the values that George Washington and Abraham Lincoln fought to put in place: our freedom and equality. As the World War II Memorial shows, victories against oppression and genocide coupled with the upholding of freedom and equality can justify war. The Vietnam War Memorial silently shouts this at us, as if to say the original intentions of the war justified it, but as the war progressed, the accumulation of white names pulled it out of the main section of the Mall and into the ground.

The Vietnam War Memorial makes many arguments as to what constitutes a truly great memorial. Maya Lin went through with her design, despite opposition, because she knew that it was something special. The memorial being built into the ground and off to the side of the National Mall's main drag shows America's opposition to troops in Vietnam. The white names on a black surface testify that the soldiers were the ones to be memorialized, not the war itself or anything the war could have gained for us as a nation. Finally, its wide "V" shape pointing at the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial remind us that if freedom and equality are in jeopardy, fighting can be necessary. The Vietnam War Memorial shows us that even on a National level, we can recognize our mistakes and attempt to heal the wounds.

[1] Webb was Marine Lieutenant and platoon leader who was awarded the Navy Cross, Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, and two Purple Hearts for his heroism in Vietnam. He then graduated from Georgetown Law School and got into Politics, becoming the Secretary of the Navy and later a Senator of Virginia (Drew 1).

Works Cited

Ankony, Robert C. "Perspectives." Vietnam Magazine August 2002: 58-61. 23 Oct. 2013. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.Drew, Elizabeth. "The Jim Webb Story." The New York Review of Books 26 June 2008. Web. 07 Dec. 2014.

"VA History." U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 17 Nov. 2014. Web. 07 Dec. 2014.

Wills, Denise. "The Vietnam Memorial's History." The Washingtonian 1 Nov. 2007. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.