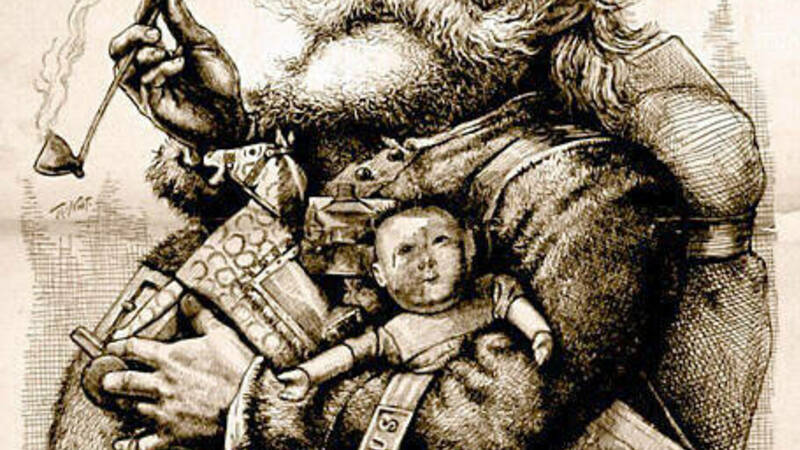

On Christmas morning, a child springs out of bed, dashes down the stairs, and stares with delight at the gifts that lie underneath the Christmas tree. With a cry of joy, the child wakes his parents and exclaims, "Look what Santa brought me!" Many embrace this image as a tender moment of childhood, but others disapprove. What, they ask, is the value of letting children believe in Santa Claus? After all, it fails to credit and foster gratitude toward the true givers, and it can even threaten to impose a materialistic outlook of the holiday, focusing too much on the presents. Most significantly, the figure of Santa Claus ingrains in children an irrational fantasy that skews their perspective of reality, leaving them unprepared for the complex, sometimes harsh truths of the real world. While these points are made with valid intentions (naïveté is certainly not a characteristic that society should cultivate), it is important to consider the reasoning behind fantasies. The ubiquity of the Santa Claus figure around the world (Papai Noel in Peru and Brazil, Father Christmas in England, and Joulupukki in Finalnd, to name a few) signifies that it is not simply a nonsensical story meant to distract children; it must go beyond the superficial in order to have remained part of so many traditions for so long. In fact, the deeper, more essential qualities that Santa Claus symbolizes—joy, hope, wonder, and generosity—are meant to inspire children through a fantastical tale. Carmen C. Richardson emphasizes this point by writing, "Fantasy for the young need not be an escape from reality; it may become, instead, a searching after the 'real'" (549). In other words, fantasy is valuable, even essential, because it gradually exposes young audiences to truth as they mature. An array of stories throughout history, literature, and film reveals the substantial veracity of imaginative tales and their positive impact on individuals. Fantasy exists in order to cultivate the fundamentals of virtue and truth, enabling children to later face the greater conflicts and complexities of life. These guiding fantasies must be distinguished from lies that seek to hide reality in order to preserve a certain state of mind, for such deceit does not stimulate security but destruction.

On September 21, 1897, the New York Sun published an editorial with a note from 8-year-old Virginia O'Hanlon, who openly presents the question, "Is there a Santa Claus?" ("Yes, Virginia" 1). The editor's reply in this newspaper article succinctly illustrates the value of fantasy, particularly that of Santa Claus. Virginia's note is formatted in such a simple, honest way (the inquisitor even makes the humble request, "Please tell me the truth") that it is hardly plausible that the editor would answer with blatant falsehood. Therefore, the powerful phrase "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus," must contain a kernel of truth (1). To penetrate this truth, it is important to know what exactly "Santa Claus" means. As the editor implies, the character should not be strictly defined as an old man who comes down the chimney with gifts. He asserts, "You might get your papa to hire men to watch in all the chimneys on Christmas Eve to catch Santa Claus, but even if you did not see Santa Claus coming down, what would that prove?" (1) Rather, the essence of this figure stems from the virtue he promotes, for "he exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist" (1). What matters is that children develop these virtuous qualities, and belief in Santa Claus can stimulate just that. The Sun editor goes on to emphasize that childlike wonder is a light that society needs, for people have been dominated by "the skepticism of a skeptical age" (1). The desire to understand and control every aspect of life has infected many hearts, which, without the simplicity of faith and hope, will find persevering through the conflicts of life more difficult. Rather than striving to cultivate an illogical or unscientific mindset, the editor uses bold phrases—such as "You might as well not believe in fairies" (1)—to venture beyond the superficial meaning of fantasy and emphasize its ability to shape character and spirit. It is inevitable that Virginia will grow out of the literal meaning of this fairy tale, but because of the tale, as well as the editor's encouraging words, she will more likely preserve the faith and hope that it taught her.

Knowing that the fantasy of Santa Claus carries such deep effects, parents should treat it with responsibility. It is true that the image of the old man with a sack full of gifts runs the risk of placing too great a value on material gain; parents can avoid this problem, however, by teaching lessons through the tradition. (For instance, children must behave, give gifts of their own to others, and get to bed on time in order to receive presents.) Of course, what causes hesitance at this fantasy is that it cannot last forever; eventually children must separate the literal from the symbolic. While parents cannot and should not prevent this realization, they can greatly reduce or even remove the pain that accompanies it. If they cultivate a healthy understanding of the fantasy that highlights virtue, it will be easier for children to naturally discern the deeper meaning of Santa Claus on their own, eventually making the more fantastical details unnecessary to them. While the traditional belief in Santa Claus is by no means a requirement to help children grow interiorly, neither is it a useless illusion, and it stands as an example of constructive fantasy.

Not only the tradition of Santa Claus, but fantasy as a whole can greatly benefit children as they grow. Richardson praises the genre because it "requires readers to look beyond the apparent, to strip a situation to its core, and to find the essentials" (549). Stories of fantasy can teach readers profound lessons in an interesting, understandable way and in the context of a safe environment. It is possible to learn the full extent of bravery by going off to war and fighting for justice, but a reader can grasp the fundamentals, the "essentials" of the same concept through a novel about wondrous challenges and quests, all in the security of his home. In her article, Richardson enumerates several concrete lessons that readers can take away from fantasy. By reading The Hobbit, one learns from the unassuming Bilbo Baggins how anyone can become heroic, or "the heroism inherent in being human." In The Wind and the Willows, the quaint yet lovable friends teach "loyalty, respect, and compassion" (Richardson 550). And the dramatic scenes of danger and sacrifice in The Chronicles of Narnia reminds one of the value of struggle and the enduring power of good over evil (Richardson 551). Just as a sugar coating makes a medicinal pill easier to take, the otherworldly elements that coat the lessons of fantasy make these lessons more attractive, comprehensive, and acceptable to readers. In this way, fantasy presents truth in small, digestible pieces that develop with an individual's mind and heart. Rather than hiding them from the problems of the world, fantasy equips readers with the tools of character necessary to improve society and their own lives.

At times, fantasy cannot only assist interior growth; it can preserve and protect it. Roberto Begnini's film Life is Beautiful uses intriguing characters and plot to reveal the powerful impact of imagination. The film tells the story of Guido Orefice (played by Begnini himself), an Italian Jew of the 1930s who lives with a childlike, carefree attitude. The first half of the movie consists of slapstick comedy that depicts Guido's lighthearted romance with a woman named Dora (Nicoletta Braschi) and his married life with her and their son Giosuè (Giorgio Cantarini). A darker tone ensues, however, when the family is taken to a German concentration camp. In order to preserve his son's innocence, Guido explains to him that the strange new environment of the camp is the setting for a game, which at times involves doing strenuous jobs to earn points, hiding, or refraining from speaking. In creating this game, Guido intends not to do harm but to keep alive a sense of hope in his son's (and therefore in his own) heart. In fact, the entire movie is a testament to the value of the game, for its conclusion reveals the narrator to be Giosuè as a grown man. Maurizio Viano writes, "Life is Beautiful is the grateful recollection of a son who commemorates his father's sacrifice in a spirit that would have pleased him" (57). Because of Guido's sacrifice, when the camp is freed, Giosuè is able to run out into his mother's arms, crying "Abbiamo vinto!" ("We won!"), joyously untouched by the monstrosity of the Nazis. Because of its largely comedic nature, Life is Beautiful has been criticized for misrepresenting and even trivializing the events of the Holocaust. However, the purpose of the movie, like the game itself, is to impart wisdom through fantasy. In the opening scene, Viano describes, "Fog makes vision difficult, and a voice-over reminds us that the film we are about to see is a fairy tale (and therefore demands the suspension of the rules of realism)" (57). The film does not seek to document the Holocaust but to illustrate in a Holocaust setting the role of imagination in maintaining hope, and this is a truth that can help audiences develop wisdom and peace in their own lives.

Knowing the power and value of fantasy, it is important to discern when a tale provides elements of truth and when it hides or degrades the truth. For instance, when a child asks his parents what death is, it would be naïve and unjust for the parents to reply that no such thing exists in the real world, that pain and an end to this life are merely fairy tales. Such a dishonest explanation would stunt the child's journey towards truth and virtue, for upon discovering the reality of suffering and death, he would feel shocked and betrayed. Confusing the wise fantasy with the "noble lie" is a danger that can damage not only parent-child relationships but also the well-being of society.

Josef Conrad's Heart of Darkness illustrates the destructive nature of lies, an entity entirely separate from beneficial fantasies. This late nineteenth century British novella follows explorer Charles Marlow, who travels into the Congo to transport ivory. Throughout his journey, he hears of a mysterious and fascinating man named Kurtz, who has supposedly brought order among the natives in the wilderness. Upon arriving to the camp, however, Marlow finds that Kurtz himself has fallen into beastly corruption, committing murder, adultery, and oppression upon the natives. On his deathbed, the emaciated man utters his final words: "The horror! The horror!" (Conrad 72) This disturbing phrase speaks to his despondent realization that man is capable of the blackest crimes. When Marlow returns to Europe to pay his respects to Kurtz's "Intended," or fiancée, he lies by telling her that the man's last words were in fact her name. He intends to protect the young woman from the harsh reality, but unlike a fantasy that points one to truth, Marlow's lie only furthers a harmful delusion that will not deepen the woman's wisdom. Marlow has recognized the repugnant hypocrisy of Brussels, the corrupt city that has grown rich through oppressive imperialism. He biblically describes it as "a whited sepulchre" (Conrad 9), but as Garrett Stewart indicates, he "washes [the city] whiter with the bleach of deceit in the course of his lying interview with the Intended" (328). Although the truth would likely be painful for Kurtz's fiancée to hear, it would lead her to a greater understanding of human nature more effectively than the naïve lie does. Because her character is so briefly and vaguely displayed in the story, is unclear exactly how the Intended would react to the truth, but it is clear that encouraging deception confines her to a miserable state of "futile pathos" (Stewart 330). Furthermore, Marlow's lie harms himself as well. Earlier in the novella, he expresses his abhorrence for lying, going so far as to equate it with death (Stewart 319). Through his dishonesty to the Intended, he kills his conscience and individuality by falling into the norm of hypocrisy that pervades society (in this case, Brussels). Just as Kurtz submits to the savagery of the jungle, Marlow likewise submits to the corrupt society that surrounds him. Unlike the fantasies conveyed in "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus" and Life is Beautiful, "Heart of Darkness" presents the story of a destructive lie, for it conceals an enlightening (albeit painful) reality and breeds corruption and deceit.

In a world that faces the disasters of violence, greed, and anger, fantasy is arguably the most needed genre of our times. It enables audiences (especially young ones) to connect with fascinating worlds, characters, and stories, helping them to grasp the most profound and necessary truths of life. With this knowledge, they will intuitively know how to apply the core values they learn to less fantastical (yet fundamentally similar) challenges in their own lives and communities. Every person deserves to seek truth, and fantasy assists in this journey, unlike the "protective" lies that seek to hide reality rather than gently lead one towards it. Hopefully, society will never fail to promote fantasy so that "a thousand years from now…nay, ten times ten thousand years from now," not only Santa Claus but all masterpieces of the imagination "will continue to make glad the heart of childhood" and so make the world a better place ("Yes, Virginia" 2).

Works Cited

Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. Ed. Robert Kimbrough. New York: Norton,1963. Print.

"Editorial of the New York Sun." Editorial. New York Sun [New York] 21 Sept. 1897: 6. Www.nysun.com. New York Sun, 12 Dec. 2012. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.

Richardson, Carmen C. "The Reality of Fantasy." Language Arts 53.5 (1976): 549+. JSTOR. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.

Stewart, Garrett. "Lying as Dying in Heart of Darkness." PMLA 95.3 (1980): 319-31. JSTOR. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.

Viano, Maurizio. ""Life Is Beautiful": Reception, Allegory, and Holocaust Laughter." Jewish Social Studies 5.3 (1999): 47-66. JSTOR. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.