Para inglês ver, for the English to see, is a Portuguese phrase that describes Brazil's agelong priority of keeping up its appearances to the rest of the world. Originally coined in terms of Brazil's avoidance of complying to Britain's slave trade regulations, this phrase is equally applicable in Brazil today with a prime example being favelas. On the outskirts of many major cities and literally rising above Rio de Janeiro into the surrounding hills, the favelas are nearly impossible to ignore. Yet throughout its recent history, Brazil has tried to cover them up. In 1992, when holding a UN summit, the government of Rio stationed military forces outside of the favelas to prevent important visitors from wandering in. More recent examples involve the global attention Brazil received when hosting the World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. In preparation for these events, Peacekeeping Police Units were stationed in favelas to get a handle on the violence. Meanwhile, favelas too close to the site of the games and the Olympic Village were either torn down and relocated or given superficial improvements to their appearance. The main drive from the international airport into Rio is surrounded by the Alemão favela, so the city built a colorful wall filled with murals, known as the 'Wall of Shame,' to prevent visitors from having a favela as their first impression of Brazil (Nisbett 39). However, despite all of these efforts to keep up appearances to the rest of the world that issues such as poverty and violence are not prevalent in Brazil, tourists still sought out the favelas. This is a trend now seen throughout the world where tourists are including slums as priority destinations, in addition to the standard religious and historical sites, when visiting new cities. As the world's population urbanizes and slums grow, the slum tourism industry continues to increase and become more relevant. In this paper, I am going to provide context into the concept of slum tourism and present its benefits and drawbacks through examples of favelas in Brazil and slums in other countries throughout the world. I will demonstrate the importance of slum tourism finding balance in its representation of poverty, concluding that when done correctly, slum tourism has the power to change the negative stereotypes associated with slums and increase individual awareness in combatting the issues that pervade them.

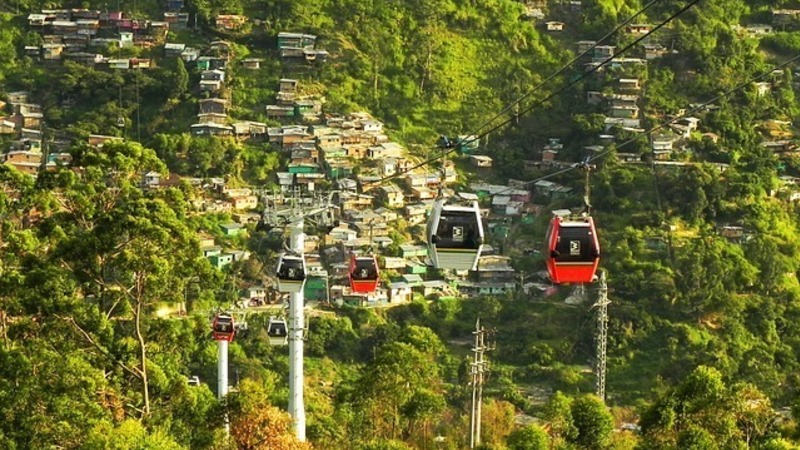

Contrary to popular belief, slum tourism is not a new idea nor a recent development by any means. The origins of this term date back to 19th century Victorian Europe when wealthy people, in Britain specifically, would go "slumming." They would venture to the East End of London, to the poorest areas, curious to view the people who lived there. This was often under pretenses of charity or philanthropy, however many "slummers" rode through on carriages accompanied by police escorts without any intention of interacting with the slums (Nuwer). These people included anyone from the upper-class such as politicians, clergymen, scientists, and even journalists. Since this era into modern times, this type of tourism has changed from being concentrated in very specific parts of the world to being more widespread and even marketed. The primary form of slum tourism takes place through "private tour companies, charities, and non-governmental organizations… as an activity in which tourists from the Global North visit impoverished urban centers in the Global South" (Nisbett 38). This form of slum tourism does not have an exact origin but can be traced back to the 1990s when people visited the townships and impoverished, segregated areas of major cities such as Johannesburg in South Africa to see first hand the effects of apartheid. This tourism was solicited by residents of the townships in an attempt to bring greater awareness to the human rights violations taking place (Nuwer). Similarly, in 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro, attracted the attention of many of its attendees to get a glimpse into favela life. Politicians, activists, and journalists alike were curious to learn about the favelas despite government attempts to keep them out by posting military outfits outside the favela entrances. These are only two of the most famous initial examples of slum tourism which has since become commonplace throughout the world beyond Brazil, South Africa, and India to major cities such as "Medellin, Colombia; Jakarta, Indonesia; Windhoek, Namibia; Kingston, Jamaica; Cairo, Egypt; Bangkok, Thailand; and Mexico City" (Nuwer). Slum tourism has become a global phenomenon increasing its relevance and the importance of its inclusion in international dialogue.

Since slum tourism directly involves people from all over the world, either as the tourists or as the attraction, the controversy surrounding this industry calls for global attention. Slumming is no longer as prevalent in first world countries as much of the destitute poverty associated with the industry has been eradicated there, despite the existence of other more systemic issues remaining. However, although the origins of slumming come from Europe, "as new housing policies and social welfare reduced slum conditions in the Global North in the second half of the twentieth century, slums started to grow in the Global South as a result of increasing rural to urban migration" (Frenzel 57). Today, the majority of the world's population lives in urban settings so it is no longer possible for slums to be a concern solely for the countries in which they are emerging. In fact, the world's rapidly increasing "urban growth takes place almost exclusively in slums, while global mobility patterns mean that migration into the cities moves across national boundaries" inherently involving more countries (Frenzel 57). As such, slums are now part of a greater global agenda. Thus, the issues that pervade slums and the industries that involve them, like slum tourism, have become part of an international discussion. Slum tourism has become so popular that there is no longer a question of whether or not its existence is ethical, because its existence is inevitable. Instead there is a call to examine models of slum tourism more carefully and find sustainable ways to make this industry have a positive impact.

Slum tourism has evolved over time from informal trips to impoverished areas to an entire market involving competition between local and commercial tourism companies. The studies done of these various industries are often on a case to case basis of just one urban setting at a time. However, through each case study, greater understandings can be drawn from the connections found in the similarities and differences in the slum tourism and the way in which it manifests itself in that particular location. One such method is the various narratives through which the tours decide to present the slum depending on the particular expectations of the tourists and the preconceived stigmatizations. The tour companies, in a sense, are selling poverty and so the package through which they choose to represent it has a large impact on the experience and understanding of the tourist. For example, "the poverty of Mumbai's Dharavi slum…is transformed by the tour into the experience of entrepreneurial spirit, ingenuity and diligence. In tours in Cape Town, poverty is translated to historical injustice as well as ethnic and cultural uniqueness, while in Rio's favela tours poverty translates into community and solidarity" (Frenzel & Koens 5). Each of these representations of the slum through the tours are intended to counteract a negative predisposition that one might have towards these areas from their representation in the media or even just from general stereotypes of poverty. Although it is important to counteract these stereotypes and offer a deeper, more complete insight into the lives of people who live in the slums besides the single story of poverty, it can be even more dangerous to only present the positive aspects of these communities.

The controversy surrounding slum tourism is based in a multitude of concerns. These concerns include the ethics of profiting off of and commercializing poverty. It can be argued that slum tourism is voyeuristic in nature and some even refer to it as "poverty porn." When outsiders enter into the slums it is important to show respect for those who live there. However, taking pictures for personal benefit without asking permission is dehumanizing to residents and glamorizes the poverty. Additionally, it is difficult to regulate the tourism industry and although laws have been introduced in some countries, none have been put into motion yet. This makes it nearly impossible to prevent commercial tour companies from exploiting the slums for profit. Interviews of local guides in the Santa Marta favela in Brazil express frustration that "'outsiders' earn money 'exploiting the favela' [as] tourism should promote local development. Community members who work with favela tourism expressed the view that they were more competent, professionally prepared and, therefore, had more legitimacy to work as tourist guides. The local guides… are poorly renumerated and have to work as second-rank 'assistant guides'" (Freire-Medeiros 154). This is a major downside to slum tourism in its current state as it questions whether or not the industry is really invested in long term economic growth for the community. An additional example is the Reality Tour company that works in the Dharavi slum in Mumbai, India. This company is credited with giving back to the community, earning little to no profit itself. However there are also greater issues within the tours it provides, such as its portrayal of Dharavi's residents and the use of guides who are not local to the slum itself. Although difficult to control, this is one aspect of slum tourism that could easily become a benefit if done ethically. On the other hand, some say that the debate over the ethics of slum tourism has become irrelevant to a certain extent because "regardless of whether the tours are arranged as exploitative moneymakers or avenues to raise awareness and give back to the community, the fact is that they are not going away" (Nuwer). In the same regard, asking the question of whether or not to go into the slums is unrealistic because "until we get rid of slums, slum tourism is going to continue gaining popularity and be here for the future" (Nuwer). As a result, the primary focus of the discussion of slum tourism should be how to ensure that it is done in the most positive and beneficial way, sparking greater interest in the issues that allow urban poverty to persist and hopefully, in this discussion, revealing ways to combat them.

A more systemic issue of slum tourism, as touched upon earlier, is the irony in the attempts of tour agencies to combat negative stereotypes of slums. The goal of these companies is often to correct the way in which slums are stigmatized by the media and the upper class. In principle, this goal is admirable and invaluable in its ability to show outsiders why slums are worth investing into. However, there are many examples of commercial tour companies attempting to "sell" the slum by only showing more developed areas and places of commerce to paint a picture of financial self-sufficiency. The fact that poverty exists is obvious but by portraying only the positive counterparts to the negative stereotypes, the suffering and hardship faced by the residents in reality is delegitimized. Tourists get a view of the slum as "a place of energy and productivity," and the residents as "industrious and resourceful. A sense of community [is] seen through smiling children and the lack of hostility. So the tour company and foreign visitors jointly construct this vision of economic success and social harmony" (Nisbett 43). These attributes exist, but they cannot be used as the single lens through which a slum is understood. In Dharavi specifically, the Reality Tours and Travel company "counteracts the notion [that] the inhabitants would be passive, lazy and inert," by focusing on "the economic activities…. Dharavi is thus presented as a place of enormous economic productivity with more than 10,000 small scale industries generating an annual turnover of 665 Million USD" (Meschkank 56). These statistics are not untrue but when taken out of the context of the living and working conditions of Dharavi's residents, they can cause misinterpretation of the slum's poverty and make it seem less severe. Similarly, Rio's favelas are represented as "places of 'authentic' culture, for example samba music and dance" which has led to the creation of the "'trademark favela', a global imaginary of the favela reproduced increasingly in films, video games, night clubs and parties around the world" (Frenzel & Koens 3). A prime example of this is the investment placed into the Santa Marta favela to become a tourist hotspot representing the best parts of the culture of the favelas. The government prioritized this favela's pacifying, placing the first Peacemaking Police Units (UPP) in Santa Marta upon the program's start in 2008, in addition to creating trams for easier public access and even a famous statue commemorating the filming of Michael Jackson's iconic 1996 music video in one of the streets. The community garnered the nickname of the "Disneyland favela" by a rapper and community leader named Fiell. His said that his reasoning for using this term was because "the bourgeoisie media always referred to Santa Marta as the 'model favela', it has been on the spotlight with the UPP. The gringos now tour the favela as if they were touring Disneyland. We residents know better, we know that we still face the same difficulties and daily oppressions"' (Freire-Medeiros 150). This idealization of Santa Marta, creates a false, albeit positive, generalization of favelas. It feeds into the exotic attraction of the culture and the uplifting ideal of community that blinds tourists from seeing the intrinsic issues favelados face. In favelas, townships, and slums alike, the construction of idealized images by tour companies is successful in combatting the negative stereotypes with which they are often associated but also undermines the problems that need attention.

By reinforcing the assumptions of tourists in their perception of happiness among slum dwellers, slum tourism can delegitimize poverty. It creates a false image of slums by only focusing on combatting the negative stereotypes instead of showing a balance of the positive attributes and the injustices at hand. This is an issue because the "normalization, romanticization, and depoliticization of poverty legitimizes social inequality and diverts attention away from the state and its responsibility for poverty reduction" (Nisbett 44). Tourists leave the tours feeling transformed with completely new perspectives of the slums but without the intention to do anything active to transform the reality of slum dwellers. They know slums are impoverished but now this poverty can be overlooked by positive attributes such as strong sense of community and a hard work ethic. So although the existence of slum tourism is inevitable and not worth debate, it is necessary to evaluate its role and to understand that it is "not a sufficient answer to a growing global problem" of poverty in its current state (44). There are ways to change this such as "tour operators could assist visitors in becoming engaged citizens [and]… help tourists to understand poverty by situating it within a politics of place, and in the context of neoliberalism" (44). Tour companies and operators have immense power in their ability to influence people's understanding of poverty and have small scale impact on individual's awareness. They can "bring tourists to the inner city… with the aim of altering perceptions, to transfer resources and to improve the neighborhoods visited while valuing their existing social fabric" (Frenzel 54). This balance of demonstrating the value of the slums while also drawing attention to the problems that need to be solved is the best way that slum tourism can have a positive impact.

Tourism does have the ability to create positive change, at least on a small scale, although it may not be able to combat fundamental issues such as poverty on its own. Tourists are changing the narrative by entering the slums and seeking out these places that for so long were ignored and isolated as a result of being written off as destitute and dangerous. By reinforcing the ideas that the slums and their residents are places of value, tourism has the potential to bring light to the culture of these areas beyond the stereotypes and shift the perspectives of the tourists to see them as places worth investing into and helping, not places to repress or tear down (Shepard). When done correctly, the tours can give visibility into the structure and self-sufficiency of slums while giving tourists the ability to contextualize the known issues that pervade them. One such method of tourism is called community-based tours. These tours have three important characteristics: using local guides, walking to increase interaction, and benefitting the community by supporting local social projects. Local guides are important because they can best offer personal insight into the history of the favela or slum and the various issues it faces. They are better able to show a balance of the positives and negatives of life in the slum instead of romanticizing them by only showing exotic cultural aspects or sensationalizing them by only highlighting the crime and violence. Walking is beneficial because tours by car can be perceived as if the tourists are on a safari gazing down at animals which dehumanizes the residents and prevents the tourists from having meaningful interactions. By walking, tourists gain a deeper insight and appreciation for the daily lives of residents, becoming more like equals instead of the barrier that the car creates. The ultimate benefit to the community is the profit that tours make being invested into local organizations and community projects ("Favela Tourism as Resistance"). If tours provide jobs to locals and include stops that interact with microbusinesses, they can contribute to the local economy. Overall, slum tourism has the ability to combat the negative stereotypes of slums and increase awareness about the issues that plague them while also showing outsiders the value and beauty of the unique culture that exists in these communities. This balance is most important because otherwise tourists' positive perceptions of the slums undermine the struggles faced by slum residents in their daily lives.

Works Cited

"Favela Tourism as Resistance." RioOnWatch, 1 May 2017, www.rioonwatch.org/?p=35171.

Freire-Medeiros, Bianca, et al. "International Tourists in a 'Pacified' Favela: Profiles and Attitudes. The Case of Santa Marta, Rio De Janeiro." DIE ERDE: Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin, vol. 144, no. 2, 2013, pp. 147–159, www.die-erde.org/index.php/die-erde/article/view/60/48.

Frenzel, Fabian. "On the Question of Using the Concept 'Slum Tourism' for Urban Tourism in Stigmatised Neighbourhoods in Inner City Johannesburg." Urban Forum, vol. 29, no. 1, 2018, pp. 51–62, link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12132-017-9314-3.

Frenzel, F, and Koens, K. "Slum Tourism: Developments in a Young Field of Interdisciplinary Tourism Research." Vol. 14, no. 2, 2012, pp. 195–212, eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/1030/1/Slum%20Tourism.pdf.

Meschkank, Julia. "Investigations into Slum Tourism in Mumbai: Poverty Tourism and the Tensions between Different Constructions of Reality." GeoJournal, vol. 76, no. 1, 2011, pp. 47–62, link-springer-com.proxy.library.nd.edu/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10708-010-9401-7.pdf.

Nisbett, Melissa. "Empowering the Empowered? Slum Tourism and the Depoliticization of Poverty." Geoforum, vol. 85, 2017, pp. 37–45, ac-els-cdn.com.proxy.library.nd.edu/S0016718517301847/1-s2.0-S0016718517301847-main.pdf?_tid=2cb4ae62-2d96-4a2d-b621-87d24a688b23&acdnat=1544392960_3f43e2f44bf0d090da45d1d917e91c58.

Nuwer, Rachel. "Who Does Slum Tourism Benefit?" NOVA Next, 15 April 2015, PBS, www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/slum-tourism/.

Shepard, Wade. "Slum Tourism: How it Began, the Impact it Has, and Why it Became So Popular." Forbes Media, 16 July 2016, www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2016/07/16/slum-tourism-how-it-began-the-impact-it-has-and-why-its-become-so-popular/#7f2bfec0297d.

Discussion Questions

- This article uses a specific example—the favelas in Brazil—to discuss a broader issue—slum tourism. How do the particular and universal interact in this essay? Are there any drawbacks to assuming the particular can speak for the universal? What are the benefits?

- The author points out that slum tourism is often accused of "poverty porn." What kind of work does a term like that do? Where does it position the audience and how does it demand that they react?

- Where would you say the author's voice is strongest? Where do we as readers move from a mitigated view of the research to the author's perspective and ideas? What do you think about locating this move here?