If a modern traveler were to voyage to the ancient shores of Rome as described by Vergil’s Aeneid and to the galaxy far, far away from Star Wars, they would traverse landscapes of stark contrast. Nevertheless, amid these differences, the same traveler would find that the mentors of both works—Anchises and Yoda—are united by a shared philosophy: Stoicism. Stoicism is an ancient philosophy that “aims to provide an account of what really is good and what really brings happiness to a human being, so that [humans] can guide [their] lives accordingly” (Durand et al. 4). The school of thought advocates for the cultivation of virtue, resilience in the face of adversity, and control of one's emotions. Since both Anchises and Yoda embody these Stoic tenets, a compelling question emerges: to what extent does the revelation of Stoic ideals by these mentors affect the character development of ancient and modern heroes, as exemplified by Aeneas in the Aeneid and Luke Skywalker in Star Wars? This paper aims to demonstrate that Stoic ideals transform the heroes’ character development by introducing them to a commitment to duty, endurance amidst hardships, acceptance of fate, control of emotions, and cosmic perspective.

To start, Section 1 analyzes Aeneas’ character prior to his meeting in the Underworld with Anchises, his father and Stoic mentor. Section 2 examines Luke’s character before he completes his training on Dagobah from Yoda, a Jedi Master and Stoic mentor. Section 3 discusses the Stoic tenets that Anchises teaches Aeneas and explains how they are later manifested in Aeneas’ character. Section 4 examines the Stoic ideals that Yoda teaches Luke and elaborates on how they later affect Luke’s character. Lastly, the paper’s conclusion explains how heroic stories have allowed Stoicism to be reborn and explored by modern audiences.

Section 1: Aeneas’ Non-Stoic Characterization before Encountering Anchises

The Aeneid, an epic poem written by Virgil in the first century BCE, narrates the story of Aeneas as he escapes from the burning city of Troy and faces numerous challenges on his heroic adventure to establish Rome. In the moments preceding his encounter with his father, which are described in Book 1–5 of the Aeneid, Aeneas does not demonstrate Stoic tenets.

To begin, during the fall of Troy, which is narrated in Book 2, Aeneas does not exemplify the Stoic principle of emotional control. As his city is being burned by the Greeks, Aeneas’ emotions overcome his ability to make rational decisions; he admits, “Rage and fury / Sent my mind reeling, and my only thought / Was how glorious it is to die in combat” (Virgil 2.372–374). According to Stoic philosophy, to live a fulfilling life, one must have control over their passions and demonstrate only their virtuous emotions in response to hardships (Durand et al. 4.7). Since Aeneas acts according to his anger and insists on utilizing warfare in response to an affliction, he cannot be defined as a Stoic hero at the beginning of the Aeneid.

In the same moment in which Troy is falling, Aeneas discovers that his divine mission is to establish a new city. As the Greeks begin their attack, Hector, a deceased prince of Troy, appears to Aeneas in a dream and declares, “Troy commends to you the gods of the city. / Accept them as companions of your destiny / And seek for them the great walls you will found / After you have wandered across the sea” (Virgil 2.347–350). From this moment on, Aeneas is made aware of his duty. Although he may have to endure difficult times, the gods will support him on his journey. Nevertheless, his strong emotions often prevent him from fulfilling his destiny.

Later, in Book 4, Aeneas’ commitment to his duty and trust in fate are again called into question when he decides to help construct buildings for Dido in Carthage. When Mercury is asked by Jupiter to remind Aeneas of his mission, Mercury notices “Aeneas / At work, towers and houses rising around him” (Virgil 4.293–294). Stoics are known for being full-heartedly committed to whatever responsibility they have; in fact, they must accept “the working out of the—rational and predictable—will of Zeus” (Durand et al. 2.8). Since Aeneas is helping Dido rather than traveling towards Italy in this instance, the hero cannot be recognized as a Stoic. Thus, emotions—in this case, his love for Dido—once again prevent him from fulfilling his mission and fate.

Finally, in Book 5 of the Aeneid, Aeneas continues to display a non-Stoic attitude when Iris convinces the Trojan women to set fire to all but four of Aeneas’ ships in Sicily. During the aftermath of this catastrophe, “Aeneas, stunned by this bitter blow, / Turned his immense troubles over and over / In his great heart. Should he settle in Sicily / And ignore Fate or seek Italy’s shores?” (Virgil 5.795–798). When Stoics endure hardships, they always demonstrate resilience (Durand et al. 4.2). However, in the face of adversity, Aeneas appears anxious and considers aborting his mission altogether.

Thus, in the first half of the Aeneid, Aeneas cannot be considered a Stoic. However, this trajectory will be altered by his encounter with his father in Book 6.

Section 2: Luke’s Non-Stoic Characterization before Encountering Yoda

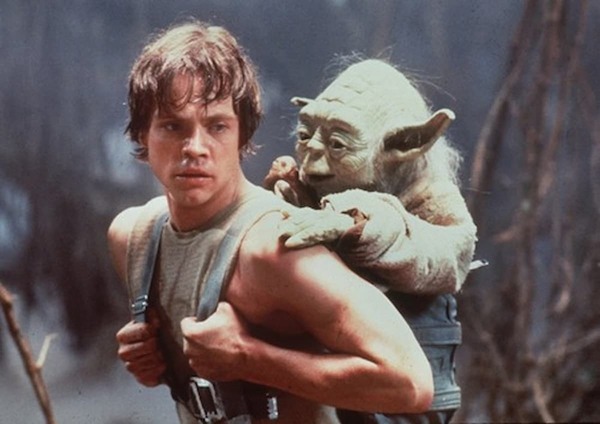

The first trilogy of George Lucas’ Star Wars (Episodes IV–VI) follows Luke Skywalker as he embarks on a mission to defend the Rebels, trains as a Jedi, and confronts Darth Vader to bring balance to the Force. In the instances preceding the meeting with his teacher, Yoda, Luke does not display Stoic principles.

At the beginning of the trilogy’s first movie, Luke does not exemplify the Stoic tenet of emotional control. When Obi-Wan Kenobi invites him to join the Rebellion, Luke immediately refuses, stating, “I can't get involved! I've got work to do! It's not that I like the Empire. I hate it! But there's nothing I can do about it right now. It's such a long way from here” (Episode IV 36:16–36:29). Shortly afterwards, when he discovers that a group of stormtroopers have killed his relatives, Luke changes his mind: “I want to come with you to Alderaan. There's nothing here for me now. I want to learn the ways of the Force and become a Jedi like my father” (Episode IV 42:15–42:25). Despite this change of heart, however, Luke does not demonstrate Stoic ideals in this instance, as he is influenced by a passionate desire to avenge his relatives. According to the Stoics, “To suffer a passion is to be in conflict with nature—to experience ‘fluttering’ rather than the ‘good flow’ of the happy person” (Durand et al. 4.7). Since Luke precisely acts according to passion, he cannot be considered a Stoic here.

In the second half of A New Hope, Luke discovers his fate of becoming a great Jedi. He is given a lightsaber as a weapon to use in order to follow the light side of the Force and fulfill his new mission. This proposal of a new destiny introduces the possibility of Luke’s conversion to a Stoic lifestyle. Although Luke initially begins training to fulfill this destiny (Episode IV 1:00:55–1:02:25), towards the end of the movie, when attempting to destroy the Death Star, he forgets about the lightsaber and reverts to his past tool, the X-wing’s targeting system. Through this choice, Luke demonstrates his persistent immaturity, which is accompanied by his lack of trust in the Force. Luke is not even affected by Obi-Wan Kenobi’s request: “Use the Force, Luke.” (Episode IV 1:55:40–1:55:44). Since “Jedi are … called upon to keep the peace within themselves by aligning their wills to the Force” (Hummel 20), at the end of this movie, Luke is still far from being a Stoic and a Jedi in this instance.

Finally, during the second movie of the first trilogy, when facing difficulties on Dagobah, Luke is not a Stoic because he fails to be resilient. When Yoda asks Luke to lift his X-wing out of the lake, Luke questions his own ability to do so. After failing to move his ship, Luke frustratedly states, “I can’t. It’s too big” (Episode V 1:10:27–1:10:30). Since Luke attempts to move the X-wing only once and immediately gives up, he fails to demonstrate endurance in the face of hardship. Moreover, in this instance, Luke is ignoring the fact that the life of a Jedi is not supposed to be easy; Jedi, like Stoic heroes, are called to face many challenges throughout their respective journeys (Hummel 20).

Therefore, in the many scenes preceding his encounters with Yoda, Luke fails to be a Jedi and a Stoic hero. A change will not happen until he hears and takes to heart Yoda’s wisdom.

Section 3: Aeneas’ Stoic Characterization after Encountering Anchises

In Book 6 of Vergil’s Aeneid, while visiting the Underworld, Aeneas encounters his father, and the latter decides to teach the former about Stoic ideals. As a result of this engagement, Aeneas becomes a Stoic.

To start, immediately upon recognizing his son, Anchises states, “You have come at last! I knew your devotion / Would see you through the long, hard road” (Virgil 6.813–814). Here, Anchises reveals the prominent Stoic principle of endurance to his son (Durand et al. 4.2). These fatherly words invite Aeneas to change his attitude. Furthermore, immediately afterwards, Anchises shows Aeneas the many souls that will give birth to the most valorous Romans, and he sets their existence within a cosmic perspective (Virgil 6.859–890). The belief that all souls belong to a higher cosmic universe is prevalent in the Stoics’ worldview: “The Stoics hold that the cosmos goes through a cycle of endless recurrence with periods of conflagration, a state in which all is fire, and periods of cosmic order, with the world as we experience it” (Durand et al. 2.5). Lastly, before Aeneas departs from the Underworld, Anchises explicitly declares his son’s fate: “Your mission, Roman, is to rule the world. / These will be your arts: to establish peace, / To spare the humbled, and to conquer the proud” (Virgil 6.1016–1018). In this instance, Anchises imparts to his son a vision of a future life filled with a destiny waiting to be fulfilled, which emphasizes the Stoic ideal of fate. Overall, during his visit to the Underworld, Aeneas learns many Stoic tenets from his father.

After his visit, a noticeable character change occurs within Aeneas. To begin, this hero displays a new understanding of the Stoic concept of fate and endurance. After a prophecy declares that he should marry Lavinia, Aeneas accepts his fate, regardless of the suffering he may face from Turnus (Virgil 7.323–330). This decision marks a contrast with Aeneas’ previous inability to accept his fate and struggles. Due to his newfound courage, Aeneas can now be considered a Stoic.

Later in the poem, after Pallas is killed by Turnus, Aeneas demonstrates the Stoic ideal of emotional control. Immediately after he is notified about Pallas’ death, Aeneas chooses to remain steadfast in his mission of defeating the Italians and confronting Turnus: “He mowed down everything before him / With his sword, burning a broad path / Through the enemy, seeking you, Turnus, / Flush with slaughter” (Virgil 10.619–622). Instead of becoming distracted by the death of a comrade, Aeneas is unaffected by the tragedy and keeps his focus on completing his mission, just as a Stoic hero would do.

At the poem’s conclusion, however, Aeneas’ possession of Stoic tenets becomes somewhat questionable. During his confrontation with Turnus, Aeneas has a decision to make: should he spare or kill Turnus? After pondering the question, Aeneas “Buried his sword in Turnus’ chest. The man’s limbs / Went limp and cold, and with a moan / His soul fled resentfully down to the shades” (Virgil 12.1155–1157). In this instance, Aeneas’ possession of Stoic ideals is disputable. On the one hand, Aeneas demonstrates his obedience to his mission and the gods by killing Turnus, as the murder enables him to establish Rome. On the other hand, Aeneas shows a lack of emotional control by acting out of revenge and murdering his enemy.

Despite this final moment of uncertainty, Aeneas’ trajectory clearly leans towards a progressive embodiment of Stoic ideals following his encounter with Anchises. The controversy of the ending cannot deny Aeneas’ construction as a hero destined to establish Rome and fulfill the gods’ plan.

Section 4: Luke’s Stoic Characterization after Encountering Yoda

In The Empire Strikes Back, Luke meets Yoda on Dagobah and receives a lesson on Stoic principles. Following this encounter, Luke starts exemplifying these same tenets.

The first piece of advice that Yoda offers to Luke is that “Wars not make one great” (Episode V 47:58–48:01). Yoda believes that to live a fulfilling life, one must exemplify peace, not violence. The Stoics themselves do not mention violence when explaining how to live a good life (Durand et al. 4.2). Next, Yoda explains that a Jedi must have a deep commitment to their duty, a serious mind, and a desire to finish what they start (Episode V 55:30–57:38). These ideas perfectly correlate with the Stoic principle of focusing on what is in one’s control and devoting oneself to their duty (Hummel 23). Moreover, while training Luke, Yoda states, “Anger … fear … aggression. The dark side of the Force are they. Easily they flow, quick to join you in a fight” (Episode V 1:01:28–1:01:35). Here, Yoda is explaining the Stoic principle of emotional control: “Remaining calm in the face of adversity and controlling one’s emotions no matter the provocation are qualities often referred to as ‘stoic’” (Hummel 22). Overall, Luke hears and learns many Stoic tenets as a result of his training with Yoda.

After meeting Yoda, a significant character change occurs within Luke. To start, the hero demonstrates the Stoic principle of commitment to duty when he decides to return to Dagobah and finish his Jedi training (Episode VI 39:33–39:59). Instead of trusting his own Jedi abilities, Luke realizes that learning the full power of the Force will allow him to confront his father in a more effective manner. Luke’s decision to return to Dagobah highlights a shared principle between the Jedi and Stoics: “Remain mindful of what is in one’s control and so use the Force as a means for good” (Hummel 23).

Additionally, Luke remains steadfast in a belief he holds about his father: “there is good in him. I've felt it. He won't turn me over to the Emperor. I can save him. I can turn him back to the good side. I have to try” (Episode VI 1:21:03–1:21:13). Here, Luke demonstrates the Stoic tenet of fate. He believes that regardless of who Darth Vader currently is, his father will eventually return to the good side of the Force. Stoics also believe that every human faces an inescapable fate that determines what will become of them (Durand et al. 2.8). By demonstrating a Stoic principle, Luke adds a modern and relatable message to the story: good can be found in everyone.

Furthermore, the Stoic tenant of emotional control is demonstrated by Luke when he has the opportunity to kill Darth Vader. When the Emperor insists that Luke should kill his father, Luke states, “Never! I'll never turn to the dark side. You've failed, Your Highness. I am a Jedi, like my father before me” (Episode VI 1:54:20–1:54:27). In this instance, Luke demonstrates the utmost control over his feelings and chooses to utilize peace. This choice makes him both a Stoic and an exemplary Jedi, as “a Jedi’s strength of mind has greater value than the ability to execute a Force push” (Hummel 23).

Based on the decisions and actions that Luke takes after encountering Yoda, the hero’s Stoic transformation is more evident than Aeneas’ transformation. This conclusion is surprising because Stoicism is an ancient philosophy. Nevertheless, this conclusion states another truth: Stoicism is very relevant to our modern world—an aspect that requires greater attention.

Conclusion

Vergil’s Aeneid and the first Star Wars trilogy were produced over two thousand years apart; nevertheless, both stories involve similar mentors that share Stoic tenets. Therefore, one may question why Stoicism is a recurring feature seen in contemporary heroes. By examining facets of modern society, it becomes clear that Stoic tenets are needed by mankind more than ever before.

When Stoicism was founded in the early third century BCE, the world was much different than it is today. Although it may be hard to imagine, the ancient Greeks did not have access to the internet, could not utilize Google to find new recipes, and were unable to send messages with the latest iPhone. Although the innovations made by companies such as Apple and Microsoft have contributed to the overall well-being of society in countless ways, modern technology has simultaneously hindered an individual’s ability to live as a Stoic. For example, social media companies create apps and services that are intentionally addictive, and as a result, modern audiences are easily convinced to ignore their personal duties and fate.

In this current cultural climate, it is not surprising to find heroes like Luke Skywalker who perfectly embody Stoicism. Such heroes challenge humanity to put aside their distractions and be present in the moment in order to discover which destiny they are called to fulfill.

At the time in which Vergil wrote the Aeneid, ancient Romans surely benefited from learning about Aeneas’ life and Stoic ideals. Amidst the frequent wars, atrocities, and struggles witnessed in the modern world, the enduring spirit of Stoic heroism emerges as a beacon of hope for the challenges that today’s society is facing. It is surely not a coincidence that George Lucas called the very first movie of the Star Wars trilogy A New Hope. Overall, Stoic heroes and heroines have made and still make the world a better place.

Works Cited

Duran, Marion, et al. “Stoicism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Spring 2023 Edition, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Hummel, Matt. “”You are Asking Me to Be Rational’: Stoic Philosophy and the Jedi Order.” The Ultimate Star Wars and Philosophy: You Must Unlearn What You Have Learned, edited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015, pp. 20-30.

Manfredi, Biagio. “Anchises and Sibyl Deifobe leading Aeneas’ Soul to Hell.” The New York Times, 10 June 2016. Accessed 4 Jan. 2024.

Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope. Directed by George Lucas, Twentieth-Century Fox, 1977.

Star Wars: Episode V - The Empire Strikes Back. Directed by George Lucas, Twentieth-Century Fox, 1980.

Star Wars: Episode VI - Return of the Jedi. Directed by George Lucas, Twentieth-Century Fox, 1983.

Still of Luke Skywalker and Yoda from the film Star Wars: Episode V - The Empire Strikes Back.

“I Wasn’t Expecting the Puppet in The Empire Strkes Back.” WIRED, 20 Sep. 2015. Accessed 4 Jan 2024.

Virgil. Aeneid. Translated by Stanley Lombardo, Hackett Publishing Company, 2005.