Could scientists 3D print a human? What about a finger? As the ability to additively manufacture and 3D print components became easier and cheaper with the 2000s, designers looked to additive manufacturing as a potential way to approach new design problems. One designer, Neri Oxaman, details her work with additive manufacturing within a biological framework in her 2015 TED Talk, “Design at the Intersection of Technology and Biology.” In the talk, Neri Oxman’s use of comparison between current design and her work establishes a base for her argument that her technology is more sustainable than current design. Oxman then utilizes different rhetorical devices to create a presentation that focuses on appeals to the audience’s values and involvement in design, which aid in creating a persuasive argument for the implementation of her technology.

Neri Oxman employs a harsh juxtaposition between manmade and natural language to appeal to the world’s rising belief that design should shift to more sustainable, environmentally friendly methods. In 2015, the same year as the TED Talk, the United Nations launched their sustainable development agenda to address the growing movement towards creating a more sustainable future. Part of the plan of action is the 2030 Agenda, which calls for creating “sustainable cities and communities” alongside “responsible production and consumption” (“Support Sustainable Development”). In the linguistic mode of the talk, Oxman “focuses on [her] language use and specific word choice” to appeal to the growing call for sustainable design (Carroll 55). Oxman highlights the difference between parts and continuous material, noting that a steel dome is “made of thousands of steel parts,” while the silk dome is made “of a single silk thread” (Oxman 00:01-00:26). The comparison between “thousands” and “single” emphasizes the difference in the large quantities of the world’s common assemblies to her new work. “Steel parts” and “silk thread” also illuminates that while her technology is still developed by man, it is entirely made of a component that has already existed in nature and was not manufactured by man. The manufacturing of “thousands” of man made steel parts can create environmentally harmful byproducts when being produced, while the cultivating the “silk thread” from a caterpillar creates no negative effect. Oxman continues that the steel dome is “synthetic,” and “the other [dome] organic” (Oxman 00:01-00:26). Directly pitting “synthetic” with “organic” suggests that Oxman’s work is produced in a more sustainable method than current design. “Organic” gives the impression that Oxman’s design can be decomposed in a safe manner, while “synthetic” brings connotations of materials that will either fail to decay, or will harm the environment. Through her careful language choice, Oxman creates an image of her work that emphasizes a new sustainable way of design in order to produce materials that do not generate negative environmental effects through their production or decomposition.

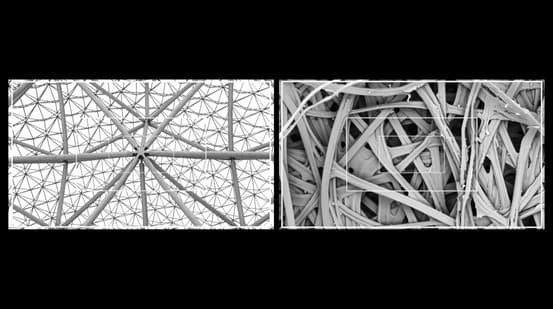

Oxman builds off of the juxtaposition to illuminate the similarities in overall function between her work and current design through the use of visual aids. The start of Oxman’s presentation immediately shows two different domes, side by side (See fig. 1), as she uses the visual aids to “position the spectator as an active participant in the making of meaning” (Benson 197). She places a manufactured dome on the left side of the visual, and her silk designed dome on the right side. As the viewer progresses from the left to right, they are invited to interpret the connection between the two domes. Oxman’s visual of her designed dome having a similar shape, structure, and background lighting pushes the audience to “make meaning” of the direct comparison between the two domes. The similarities in the visuals allows the audience to imply that the new design has an analogous function to the one of the currently accepted dome. Oxman continues by using a technique of reframing the photographs in order to “provide close-ups of [things] barely noticeable in the original photograph, thus inviting viewers to question why this is so” (Lancioni 398). She drastically zooms in on the two domes to show their structures (See fig. 2). The clear similarity in color and web-like appearance pushes the audience to draw the conclusion that the function and structure of the newly designed dome follows the current approach, but takes a new approach. Oxman then looks to influence the connotation the audience has with her new design by placing visuals of models wearing her work on modeling runways (See fig. 3). The visual of the technology in a modeling show encourages the audience to associate runway fashion qualities of luxury, high quality, and innovation with Oxman’s work. Oxman’s use of visual aids helps her subtly promote the message that her new technology has a proven function and is a higher quality product in comparison to current design.

After using visual aids to cement the logistical appeal of her design, Oxman seeks to appeal to the emotional response of the audience through the use of religious values within a biblical allusion. According to a Pew Research Center demographic analysis in 2015, Christians made up about 31% of the world’s population, the largest religious group in the world (Hackett and McClendon). Knowing that her talk will reach a large global audience due to TED’s prominence, Oxman “tailor[s] it to a particular audience” through the use of a biblical story (Herrick 19). Oxman recalls a biblical story where there was a fruit tree, but “there was to be no differentiation between trunk, branches, leaves and fruit. The whole tree was a fruit” (Oxman 5:40-6:42). She uses the story to emphasize that the tree is made of a single part, similar to the production of her own work. Immediately after introducing the story, Oxman claims that her team “looked for that biblical material,” and “found it” (Oxman 6:42-7:15). The description of finding biblical material creates an implicit comment on the material of Oxman’s design. Oxman attempts to “alter the symbolic framework [her audience employs] to organize their thinking” so that a religious audience immediately associates their predisposed, positive, biblical qualities with her work (Herrick 19). Oxman’s awareness of the audience and her talk’s outreach allows her to effectively persuade a portion of the audience by connecting her work to their deeper, unwavering personal values.

Oxman expands on her emotional appeal by establishing a personal bond between the audience and her work. She utilizes displaying human emotion and using collective pronouns in order to construct a personal bias for the audience’s view of her technology. Oxman introduces her team with a photo board of their headshots, and a picture of their hands next to them. Suddenly, the students begin to laugh and smile, while their hands begin working on different tasks next to each other (Oxman 2:29-3:27). The emotion that is displayed in the video allows Oxman to effectively “persuade through the character” of her team by showing the audience that they are not a distant group of scientists, but resemble the people sitting besides them (Selzer 287). The audience having a more grounded connection to the team enables Oxman to directly include the audience in her work, telling them that “[w]e live in a very special time in history, a rare time” (Oxman 2:29-3:27). The use of the collective “we” immediately places the audience within a context of Oxman’s work. They are not just observers of a creation, they are active participants in the change her work is bringing. Oxman also focuses on describing the time period as “special” and “rare” to give the audience a unique sense of relation to the project; they are the first ones throughout their genealogy who can experience Oxman’s work. Oxman’s ability to give the audience an interpersonal relation to her work puts them at a disposition to be more accepting of new views and potentially have a subtle bias towards the work they are connected to. Oxman’s progression from a logical comparison of her work and current design to an emotional appeal towards her audience’s values signals a focus on the connection between her technology and the audience.

A critical analysis of Oxman’s talk suggests that she uses a deliberative styled approach in her claims in order to achieve a single goal of having her work adopted by society. Selzer characterizes deliberative rhetoric as being “organized around the kinds of decisions a civic or social organization must make (about a future course of action)” (Selzer 284). Oxman describes her collection of wearable technology as “the future of our race on our planet and beyond,” which will help society “move away from the age of the machine” (Oxman 11:39-12:37). Oxman gives the audience a blueprint for the future of technology with her work, and proposes that the audience must choose to adopt the new technology over the current systems in place. The use of deliberative rhetoric establishes a forceful tone, suggesting that Oxman’s main goal is to push her technology for its own success.

While Oxman’s use of deliberative rhetoric may underline an ultimate goal to have her work adopted by the current world, her focus on incorporating epideictic rhetoric creates a more persuasive argument for adopting her work. By focusing on the community the audience is a part of, Oxman articulates an overall goal of improving society through reevaluating design beliefs, something that is more inclusive of the audience’s interests. Selzer claims that “in epideictic discourse, the audience is asked to reconsider beliefs and values” (Selzer 284). Oxman challenges the audience’s views on design by asking multiple questions, such as “[w]hat would design be like if objects were made of a single part?” (Oxman 5:40-6:42). Oxman specifically questions the current assemblies that are made up of thousands of parts, and are integrated into daily life. While her technology fits the criteria of being a single part, Oxman aims to question how the current world could view design in new lenses in order to improve. After asking the audience to reconsider the current state, she then asks, “[w]ould we return to a better state of creation?” (Oxman 5:40-6:42). Oxman asking if adopting new beliefs would not only change the current system of design, but “return” to a “better state” suggests that the present design process is flawed, but she does not immediately follow that her work is the solution. Oxman’s deliberative rhetoric tells the audience that they must accept her work, but the epideictic rhetoric gives the audience agency. The audience feels as though they are tasked in assessing how their community adopts design standards because Oxman makes them feel as though they have a choice in what the standards are. Owing to Oxman's strategic framing of her argument, the audience has the agency in deciding to adopt Oxman’s design and is able to enthusiastically drive the direction of the future.

Neri Oxman’s use of rhetorical strategies helps her create a persuasive argument for the audience to reconsider the design values that are currently being deployed. Oxman pushes her own technology, but also raises the question of how the world can adapt to more sustainable design through additive manufacturing. Can whole buildings be 3D printed with organic materials? Can a building be composed of a single component? By reconsidering how to design, the world can investigate new sustainable approaches to old and arising problems alike. With additive manufacturing, the future of human design may lead not only to new technological breakthroughs, but also a more symbiotic relationship between the Earth and its inhabitants.

Works Cited

Benson, Thomas J. “Respecting the Reader.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 72, no. 2, 1986, pp. 197-204.

Carroll, Laura Bolin. “Backpacks vs. Briefcases: Steps Towards Rhetorical Analysis.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writings, Vol. 1., edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, Parlor Press, 2010, pp. 55.

Hackett, Conrad, and David McClendon. “Christians Remain World's Largest Religious Group, but They Are Declining in Europe.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 31 May 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/05/christians-remain-worlds-largest-religious-group-but-they-are-declining-in-europe/.

Herrick, James A. “An Overview of Rhetoric.” The History of Theory of Rhetoric, 2nd ed., Allyn and Bacon, 2001, pp. 19.

Lancioni, Judith. “The rhetoric of the frame revisioning archival photographs in The Civil War.” Western Journal of Communication, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 397-414.

Oxman, Neri. “Design at the Intersection of Technology and Biology.” TED, October, 2015, https://www.ted.com/talks/neri_oxman_design_at_the_intersection_of_technology_and_biology/transcript.

Selzer, Jack. “Rhetorical Analysis: Understanding How Texts Persuade Readers.” What Writing Does and How it Does It, edited by Charles Bazerman, Paul Prior, Routledge, 2003, pp. 284, 287.

“Support Sustainable Development and Climate Action.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/our-work/support-sustainable-development-and-climate-action. Accessed 6 March 2023.