Wes Anderson's 2014 eccentric hit, The Grand Budapest Hotel, is a very unique piece of cinema. It is told as a story within a story within a story, and at first the film's oddities do not seem to have any meaning beyond sheer whimsy. However, as the movie progresses, it becomes clear it is struggling with deeper issues regarding history and how we in the present remember it. In light of these later themes, the rhetorical strategies used in the opening of the movie become much clearer. Even in the first few minutes, it portrays a back-and-forth between idealized and clearheaded views of the past. In the opening scenes of The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson uses visual rhetoric to convey the theme of memorializing a treasured past, counterbalanced with a technique of passing the audience's lens backwards in time so as to reach a more objective point of view.

As can be seen towards the end of the film, one of The Grand Budapest Hotel's major themes involves preserving or looking back on a treasured past. Zero mentions how Mr. Gustav preserved a dying "world" for a short time, even though it had largely disappeared before he entered it. Zero himself preserved the memory of his wife and Gustav in the hotel, the Author preserved Zero's story, and so on and so forth, each step looking back farther and farther and thus making the events more and more idealized. It is not clear whether Anderson thinks the preserved history has much value, having been re-processed and reexamined so many times, but what is clear is that one of the film's major themes is how people view the past, contrasted with the actual nature of these past events. Anderson strikes a balance between the two perspectives, sometimes implying a character's rosy recollections about the past, at other times shifting the audience's lens to a more objective viewpoint. Aside from the conclusion, the back-and-forth of these two themes is most obvious in the introduction of the film.

At the very beginning of The Grand Budapest Hotel, the past being memorialized is the life of the Author, and the lens of the audience passes from the woman with a book to him. At the very end of the opening credits, while the majority of the screen is still black, a short introductory heading appears giving basic exposition on the settings which follow. More importantly, the font and capitalization style both suggest old newspapers or inscriptions. This immediately gives a sense that the scenes which follow are retelling an old, memorialized story, which is in fact what occurs. The first true scene of the movie is a still shot where the faded words, "Old Lutz Cemetery," are immediately obvious on screen, which implies the same sense of major events in the past being memorialized and retold. This is further hinted at (albeit even more indirectly) by the snowy, wintry setting–old, dead, or dormant things are still preserved for a time by the frost. The only movement in the frame at this point is a woman walking into the cemetery; she is the audience's lens for the first few seconds of the film. The camera cuts to a tracking shot of this woman walking through the cemetery with gravestones all around her, which conveys a sense of the history through which she is passing. The ultimate focus of that history becomes clear in the next shot, with a tall memorial to the Author, standing alone. He was clearly an important man, as the gravestone stands in a completely separate part of the yard. Moreover, when the camera cuts to a closer view of the statue, it becomes clear that the man is much admired. There are numerous keys hanging from the gravestone, left there by his enthusiasts, as well as an inscription reading, "Our National Treasure." The way this scene is constructed clearly points to the Author being a valued figure from the past of this nation, but it also suggests the shift in perspective that is soon to follow. When the woman approaches the Author's grave, the camera stops tracking her and instead cuts to the memorial, forcing the woman to walk into frame for the first time since the beginning of the scene. Furthermore, the gravestone is significantly taller than she is, so she is constantly looking up at the bust of the Author's face. However, the most significant indicator of this lens shift is when the woman places a key on the memorial–in doing so, she hands off the audience's viewpoint to the Author himself, who is the subject of the next scene.

When focusing on the Author in his later life, Anderson uses visual rhetoric to reveal the past is not as rosy as the previous scene imagined, while also setting up another glowing past that the Author perceives. As the camera cuts to the live Author for the first time, several things are immediately noticeable which indicate that the Author is filming himself speak. The frame contracts slightly, gaining the smoother edge of physical film rather than digital recordings, a whirring noise comes on in the background, and a rectangular section of the background is much more brightly illuminated than its surroundings. All of this suggests an older camera running on physical film, neatly confirmed when "1985" appears unobtrusively at the bottom of the screen. Why do these changes matter? The perspective shift and camera are important for two reasons. Firstly, it indicates the audience is no longer looking back at the past, with all of the wishful thinking that entails, but instead observing past events as they actually occurred. The viewers' lens is now a camera in 1985, instead of a woman looking back at 1985 from the present day. Moreover, the audience can see what the Author's camera is recording and what it isn't, so the difference is clear between what he wants to preserve for the future on the one hand and reality on the other. Most noticeably, the section of the background which the camera is illuminating contains a bookshelf with several trophies, and the corresponding part of the Author's desk is clean and neatly organized. All of this lines up with how the Author is seen in the present day–he is respected as a great figure in Zubrowka's history, a "National Treasure." However, what is outside the camera's illumination paints a somewhat different picture. The outer bookshelves are much more cluttered, and the sections of the desk outside the illuminated area are absolute disasters, cluttered with piles of papers and books. Furthermore, the Author appears snappish at times, as when he yells at the boy, and somewhat stressed, as he accidentally repeats to the camera an apology which the said boy whispers in his ear. So over all, the real Author does not seem as distinguished and proper–not as ideal–as how he is remembered.

Although the Author does not live up to how history views him, The Grand Budapest Hotel strongly implies he has a similarly rosy view of his own past. At the end of the scene with the Author in his office, he begins to tell the story of his experiences at the Grand Budapest. Immediately, the camera cuts to a wintry landscape, with several other significant changes. Primary among these is the change in aspect ratio from 9:16 to 3:4. This strongly implies one looking back in time, as the 3:4 ratio is commonly associated with old films, while 9:16 is more commonly employed in modern movies. The scene is also very snowy, again implying a preserved or memorialized past. Moreover, the entire landscape seems more "pinkish" than one might expect–the Author is looking back at his past with a literal rosy tint. When the camera pans to the "town," with the hotel prominently displayed at the top of a hill, it becomes clear that the entire shot thus far has been of a mechanized diorama. This, combined with the aforementioned visual rhetorics, gives the entire scene a feeling of quaintness. The Author is looking back at this point in time as simpler, calmer, better than his present life. However, that perspective does not stay in place when the audience's lens shifts again.

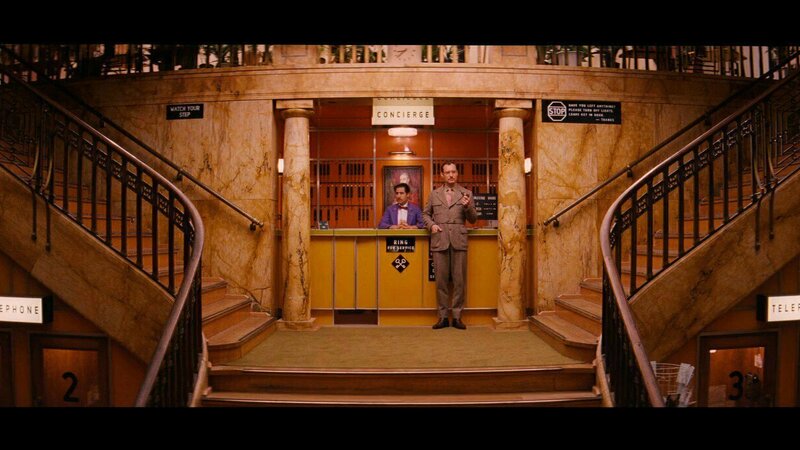

Towards the end of the introduction, in the scenes depicting the younger Author and his stay at the Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson again uses visual rhetoric to undermine the "rosy view" of the past in one case while also setting up another, more mysterious view of an earlier time. These transitions occur through a change in the viewers' perspective, this time between the older Author and his younger self. When the camera zooms in on the hotel model in the diorama, Anderson employs a graphic match and cuts to a live shot of the same hotel. Again, this shift is accompanied by several rhetorical changes. First and foremost, the Author's narration becomes audibly younger-sounding, directly indicating that our perspective has changed. It is also implied more subtly in that the season changes from winter in the diorama to fall in the real world. The clock has been wound back somewhat, and the world we are viewing is in a time of change and fading, but it is not dead (i.e. wholly in the past) yet. Moreover, the real hotel is much shabbier than its diorama counterpart, so the audience can see immediately that the Author's perspective later in life was not entirely accurate. Once the Author enters the hotel, the visual rhetoric employed again indicates a sense of age, but no longer suggests fond remembrance. In the hotel, everything takes on a yellow tinge like old, faded film. It implies an environment preserved like a fly trapped in amber, rather than memorialized. This is fitting for the audience's current lens (the young Author has no reason to fondly remember the hotel's glory days), but it more importantly allows Anderson to get to the core of the plot by introducing an element of mystery– Zero Moustafa. Zero is given this mysterious air in part by the soundtrack, but also by subtler techniques, such as dark glasses which obscure his eyes and camera angles which rarely show his full visage. The newspaper clippings displayed during Mr. Jean's conversation with the Author clearly indicate that Zero has a long history, but in this case the history is mysterious, not rosy. However, when the context is considered this is not, ultimately, a break in the pattern. By making Zero's history mysterious, Anderson makes the audience care about his story much more than through the fond recollections of the previous lenses. And since Zero's story makes up the core of the film's plot, it is in the conclusion of said story that Anderson most clearly communicates his messaging about a fondly-remembered past. After all, at the end of his tale Zero fully describes the layers of past recollections that make up his story (i.e. Mr. Gustav's disappearing world), as well as his thoughts on preserving said past. So by breaking the general pattern in one instance in the introduction, Anderson is able to later communicate the same idea much more strongly.

In conclusion, The Grand Budapest Hotel uses visual rhetoric in its opening minutes to suggest two major themes found later in the film: the value of memorializing or recalling a treasured past, and in contrast the necessity of cutting through to events as they actually occurred. Anderson does not seem to favor either theme, but the general parlay between the two which he outlines (through Zero) in the conclusion is also present in the introduction. At first, the history being memorialized is the life of the Author, seen as a "National Treasure" in the present day. However, when the viewers' lens is passed to the Author himself, it becomes clear his life was not as idealized as later generations would recall. Furthermore, the Author appears to have fond memories of his own relating to the Grand Budapest Hotel; these recollections, too, do not accurately reflect the reality depicted through the eyes of his younger self. The young Author encounters memories of the past as well, in the form of Zero Moustafa, but here Anderson breaks pattern slightly. The history which Zero embodies is treated with more mystery than fondness– it does not fit as well into the overall theme, but it ultimately allows Anderson to address the contrast between events lived and events remembered at the conclusion of the plot. Here, speaking through Zero, he clearly outlines the dilemma for the audience to consider: in the end, was it worth it? Is the brightly-viewed memory of the distant past of any value, considering how poorly it ends up reflecting reality? While The Grand Budapest Hotel never fully answers that question, it gives its viewers hope that the answer might be yes.