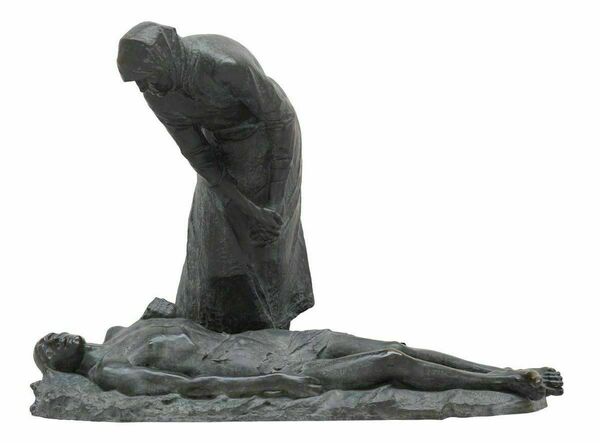

Born April 12, 1831, Constantin Meunier spent his career in art as a painter and sculptor. He spent much of his early career up through the 1870s painting religious themes in works such as Lamentation (1870) (fig. 1),[1] but later that decade, after having been asked by Camille Lemonnier of Le Tour du Monde, turned to making illustrations of factories, mines, and their workers.[2] Catherine Labio called this event “a turning point in Meunier’s career.”[3] From that point forward, labor became the central topic of Meunier’s art, including the sculptures of laborers for which he is most famous, and the painting Landscape with Factory (1886) (fig. 2).

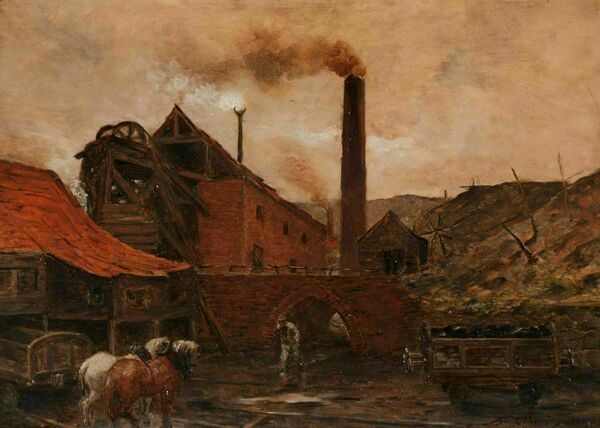

To give a preliminary visual analysis of the work, Landscape with Factory, an oil painting on panel, is exactly what its title suggests; it features a desolate Belgian Black Country setting with dead trees on a darkened hillside and a decrepit factory with billowing smokestacks, opposite to the hillside. At the piece’s foreground stand two horses, a hunched-over laborer emerging from a shadowed arch, and a coal cart. The sky is a hazy brown from the ever-flowing smoke. Upon first glance, the piece carries a lonely and dour feeling.

Not all of Meunier’s depictions of labor are like this. In fact, he is best known for his idealized portrayals of labor; however, while many of Constantin Meunier’s works focusing on this subject of labor tend to show an idealized view of the subject, in Landscape with Factory, Meunier departed from his usual depictions of labor to give a much more somber view of the labor scene in an economically struggling 1880s Belgium.

To prove this point and better understand Landscape with Factory, it is necessary to have background knowledge of Belgian history in this time period. Nineteenth-century Belgium was essentially divided into two regions: the “agricultural Flemish-speaking regions” and the French-Speaking industrial regions, known as Black Country.[4] As Belgium industrialized (focusing primarily in the industries of coal and iron), the nation became rather wealthy, but this wealth did not extend to the working class.[5] When Belgium faced an economic depression in the 1880s, workers began to riot and strike in 1886.[6] These riots happened at right around the time that Meunier painted Landscape with Factory.

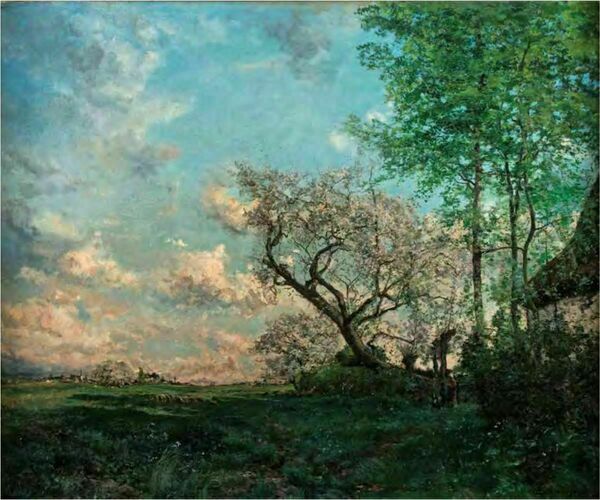

In the years leading up to the economic hardships of Belgium in the 1880s, Belgian landscape painting focused on showing idealized natural scenes, as seen in Fourmois’s La Hulpe (1865) (fig. 3) and Boulenger’s Back on the Farm (1869) (fig. 4). These utopian portrayals of nature served as a “nostalgic ‘return to nature,’” in a time when the Belgian countryside was becoming Black Country, but once the 1880s hit, Belgian landscape underwent a thematic shift, explicitly into the theme of industrialization.[7] The clear skies and green fields were replaced by large, brooding factories and their plumes and plumes of smoke.

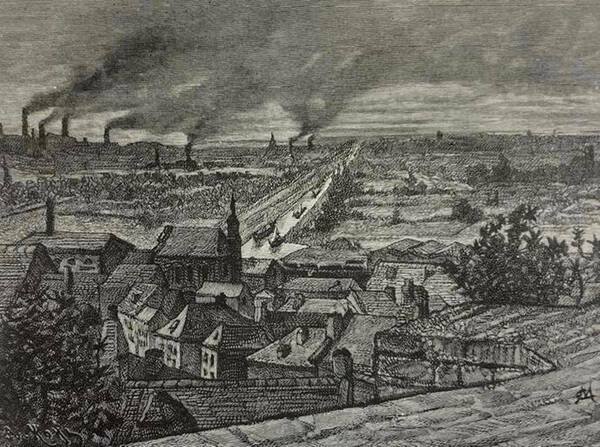

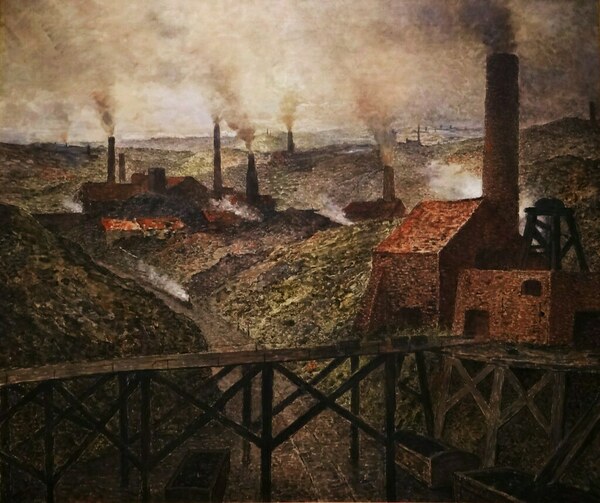

Meunier himself did not go through this exact transition from naturalistic landscapes to industrial landscapes, but when he began depicting industrial landscapes, he did so effectively. In his The Environs of Mons, View Taken from the Château (n.d.) (fig. 5), Industrial View of the Borinage (1882) (fig. 6), and The Red Roofs of Pâturages (1885) (fig. 7), Meunier expertly showed the factories’ pollution of the skies. The smoke in these works flows seamlessly into the skies, so that the end of the smoke and the beginning of the clouds cannot be perceived. While the ominous smoke and skies provide a window into the dangers of industrialization, the foreground and natural scenery within these works is still somewhat vibrant and comforting.

Landscape with Factory is different from many of Meunier’s other industrial landscape paintings. The sky also features the seamlessly transitioning smoke, but the color of the sky suggests a level of pollution a degree above that in the other mentioned works. The smog-like haze permeates the entire painting, making everything a bit blurred.

Additionally, it is worth noting the desolation of the natural scenery, surrounding the man-made factory and shed. In the entire work, there does not appear to be a single living plant, other than perhaps the occasional brown-green streak on the hillside on the right. Othewise, the ground is a dark brown, moist mud. While it does not seem to be raining in the painting, it looks as though it just has; the laborer trudges towards a puddle at his feet. The most ominous element of the depleted nature is the pointy, leafless trees on the hill. The bare branches cannot bring any fresh oxygen into this setting. One can imagine what it must be like to breath this air.

One last element of the scenery in Landscape with Factory sets it apart from many of his other landscape paintings, and that is the decrepit condition of the factory and buildings. Starting with the building in the bottom left of the scene, its façade looks worn down and blackened, and its red-orange roof sagging down, rather than the sharp and more linear roofs Meunier features in Au pays noir (1893) (fig. 8).

The large factory building in the center of the painting looks equally broken down. The machinery attached to it creates a gnarly mess of wooden beams, and the opening in the wall underneath the roof creates a vacuum that sucks the eye into its empty blackness. The cabin-like shed to the right of the large smokestack looks pathetic and monochromatic, and it stands ever so slightly crooked. Even the handrail on the footbridge is warped. Only the monolithic smokestacks stand tall and straight.

Landscape with Factory’s buildings are reminiscent of the Dutch “rustic ruins” that Walter Gibson has studied.[8] Though hard to see its details, Emmanuel Murant’s Farmhouse in Ruins (n.d.) (fig. 9) in particular is strikingly similar to Landscape with Factory. The Dutch work also features a crooked, caving-in roof, a hole in the top portion of the farmhouse wall, a worn exterior, and a tall, smoke-producing chimney.

There is a strange appeal to Meunier’s painting and the rustic Dutch works. Their subject matter could conventionally be described as displeasing to view, yet they are perfectly eye-catching. Gibson wrote on this matter, “There is considerable evidence that rustic decay and neglect could evoke ideas of a positive kind. One is the humble life, the life of virtuous poverty.”[9]

It is doubtful that Meunier attempted to create a scene of virtuous and Christ-like poverty in Landscape with Factory, but there is indeed something calming about the utter desolation of the landscape. The largest smokestack featured in the work creates a line of symmetry between the large factory building and the hillside. Each is entirely worn down and dead, thus creating a complete sense of stillness, with the exception of the plumes of smoke or the trudging steps of the laborer. From this stillness comes the eerie calm that makes Landscape with Factory so captivating; but while it is captivating, it is by no means an idealized depiction of labor.

From the “nostalgic ‘return-to-nature’” landscapes and the later industrial landscapes to Meunier’s sculptures of laborers, Social Realism is present. The Frenchman Gustave Courbet, who was integral to the embrace of Realism in Belgium and considered to be “one of the three great realist painters,” along with Adolph Menzel and Thomas Eakins,[10] defined a Realist as “a sincere lover of the honest truth,” and this truth included that of the working class, who were not often depicted in art until the rise of Realist art.[11] Throughout the nineteenth century, Realism had revolutionary implications, and as Labio explains, “Realism shocked, not only because it depicted lower or ‘vulgar’ subjects, but because its monumentalization of such subjects was rightly viewed as a challenge to the existing order.”[12]

In the pre-1880s Realist landscapes, like Courbet’s Landscape at Ornans (1855) (fig. 10), it is nature that is monumentalized. These idealized scenes act as a subtle reminder of nature’s beauty and importance in a time when industrialization reigned supreme. When the landscape scene shifted in the 1880s, industrialization and its issues were brought directly to the forefront of artistic expression. At the same time, beyond the bounds of landscape art, the laborer began to be monumentalized.

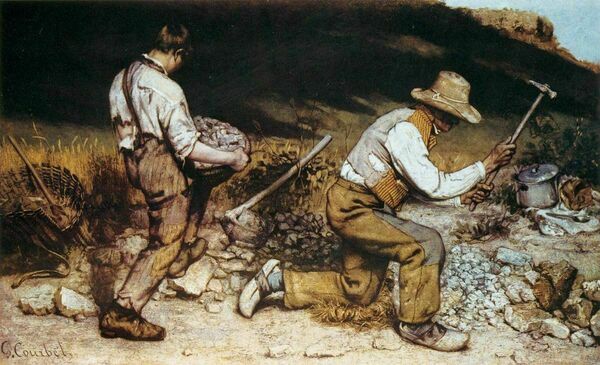

Courbet’s Stonebreakers (1849) (fig. 11) shows this Realist focus on the laborer. This painting shows two men, each with tattered, patched, and ripped clothes, working to clear a road. The man on the left awkwardly carries a large rock, and the man on the right, with his straw hat providing shade for his face, hammers away at a pile of stones. On the painting’s right lies a pot for food and a bag, both resting on a dirty blanket. This is not an idealized depiction of labor. It is gritty, and the two men’s struggles are portrayed.

While Frenchman Courbet was able to depict some of the grimmer elements of labor in his Realist art, this was not as common in Belgian art. This was due to a fundamental difference between Courbet and Belgian culture. Courbet called himself “not only a socialist, but a democrat and a Republican as well—in a word, a partisan of all the revolution.”[13] This view contrasted greatly with Belgium, in which even the nation’s own Belgian Workers’ Party “stressed evolution over revolution.”[14] This is not to say that there were not calls for change and better protections for workers in Belgium, but as Labio frames it, “The country had defined itself as an industrial and economically successful nation, staking its national pride and identity almost solely on its ability to generate wealth through industrialization.”[15] In fact, Belgium had its own industrial publication, referred to as “a vanity project for the individual factory owners and a work of propaganda.”[16]

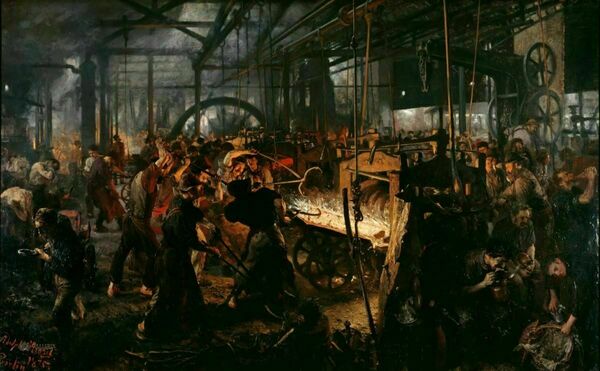

Given Belgium’s identity as an industrial nation and its distaste for revolution, it makes sense that Belgian Realist art would not exactly be radical in its depictions of art, and the same is true for much of Meunier’s art. In comparing his relief sculpture Industry (1894) (fig. 12) to Menzel’s Iron Rolling Mill (1875) (fig. 13), some of Meunier’s tendencies appear. Michael Fried notes about Menzel’s labor scene:

There is also something painful to contemplate in the instruments the men in the central group are using, or rather the interplay of the strained and awkward actions of the men, the long-handled tongs they are wielding with great effort, and the fiery cast iron. (The physically deforming nature of the work is epitomized by the monstrous dark silhouette of the upper body of the worker seen from behind.)[17]

In Meunier’s sculpture, the laborers do not appear to undergo the same struggles or, at least, do not appear to struggle with the same difficulty that they in Menzel’s do. Meunier sculpted a group of men working as a machine, all shirtless and with rippling muscles. While Menzel used Realism to create a scene of toil, Meunier used Realism to create a scene of idealized workers.

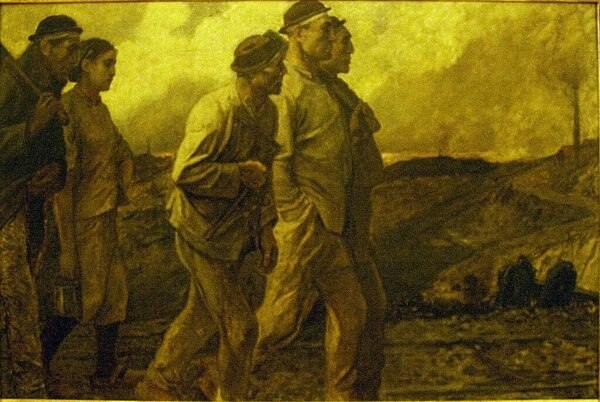

Idealizing laborers is a recurring motif in Meunier’s work. He did such in The Return of the Miners (n.d) (fig. 14), in which the workers stand tall and bravely march towards their tasks. The tallest miner nonchalantly has his hands in his pockets and a calm expression. The scene looks like that of the protagonists in a movie walking in slow-motion with their backs to an explosion. “The landscape is secondary to figures.”[18] This is an idealized depiction of labor.

In his sculpture The Firedamp (1889, fig. 15), Meunier made the scene of the mother identifying her dead son into a sculpture with Christian iconography of Mary and Jesus after he was taken off the cross, and in doing so, Meunier found a way to idealize a scene of death. The Firedamp looks almost exactly like his earlier painting of Mary and Jesus, Lamentation. Christian Brinton had an interesting take on the consistency of Meunier’s art even through his thematic shift from religion to industrialization:

The subject-matter [industrialization] was new, yet [Meunier’s] attitude toward it remained identical. He had simply forsaken the heroes and martyrs of faith for thosechumbler though no-less touching victims of economic pressure and distress. He had merely exchanged cathedral and cloister for factory and furnace. His monks became miners, his sisters of charity, colliery girls. Out of modern industrialism he forged his own religion.[19]

Meunier often depicted his laborers with a reverence; they “are idealized, heroic figures, untouched by illness or injury.”[20] But in doing so, his labor depictions were viewed in a somewhat counterintuitive way.

In the early 1910s, labor strikes and violent riots broke out in the Colorado Coal mines, and there were fears of revolution.[21] Exactly during this time, an exhibition of Meunier’s works came to America. Rather than fanning the flames of revolution brewing within the American workforce, Meunier’s exhibition aided in quelling them. This happened because, as Melissa Dabakis argues, Meunier’s idealized depictions of workers “reflected a stable social order,” adding that, “While seeming to present a progressive vision of labor in society, this exhibition served the status quo.”[22] Labio sums up the effect that Meunier’s popular work had quite well:

Meunier’s heroic depictions of miners and hiercheuses found success in part because while they elicited sympathy and identification on the part of the viewer, the emphasis on workers’ nobility also allowed viewers to look away from the human cost of physically destructive labor and unhealthy working conditions.[23]

To summarize this, Meunier’s most popular works, including his sculptures of miners and other laborers, found success because they made the viewer feel sympathetic but comfortable in a time where labor crises engulfed Western society.

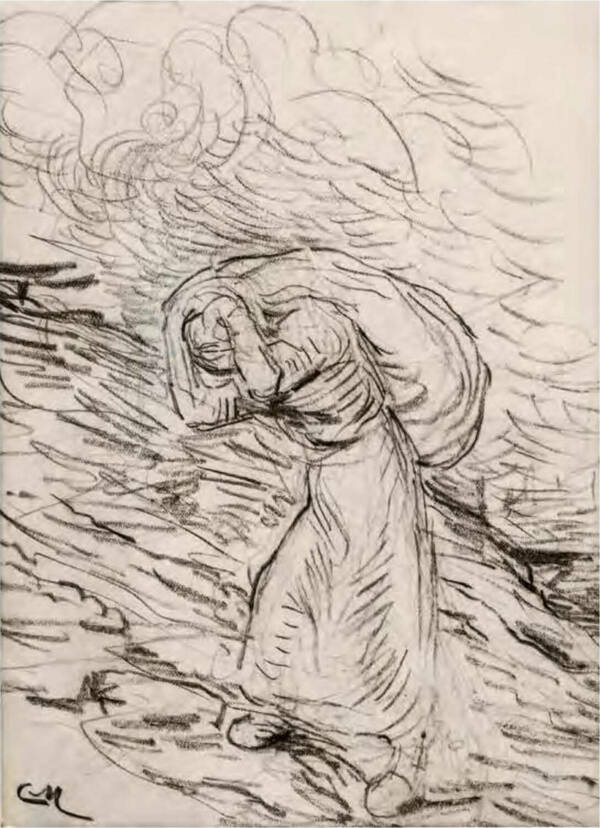

Landscape with Factory is by no means one of Meunier’s most popular works, and the depiction of the laborer within it is in no way similar to his depiction of laborers in works like The Return of the Miners. The lone laborer more closely resembles the hiercheuse in his drawing Hiercheuse Climbing a Heap of Coal (1885) (fig. 16). In the drawing, the woman is hunched over with her head down. She struggles under the weight of the coal that she carries. She is alone.

The laborer in Landscape with Factory struggles much like the hiercheuse. His head faces down. He hunches forward as he trudges from under the arch, taking step after step in the dark mud. While the facial expressions of the workers are clear in The Return of the Miners, this laborer has no expression and no identifiable face. He is isolated, even from the viewer in this sense. This is not one of Meunier’s idealized depictions of labor.

To give some final thoughts about Landscape with Factory, it is important to identify the specific historical context surrounding the work. As for this historical context, 1886—the year in which Landscape with Factory was painted—was a significant year in Belgian labor history. The fact that the year Meunier painted this work is the same year that strikes and riots broke out in Belgium is no coincidence. Landscape with Factory’s dark and somber mood reflects that of 1886 Belgium.

Overall, Landscape with Factory differs from many of Constantin Meunier’s other works. Considering the lengths he went to show desolation in both the land and the buildings with the hazy brown that touches not only the sky but everything else in the work, and given how that is complemented by the lonely, anonymous worker with his uncomfortably slouched posture, Landscape with Factory serves as a rare depiction of the negative nature of labor in Meunier’s works, and a rare depiction of the negative nature of Belgian Realist art as well.

[1] Jeffery Howe, “Nature’s Mirror: Reality and Symbol in Belgian Landscape,” in Nature’s Mirror: Reality and Symbol in Belgian Landscape, ed. Jeffery Howe (Newtown, MA: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2017), 23.

[2] Catherine Labio, “‘Belgium is an Industrialist’”: Pride and Exploitation in the Black Country, 1850-1900,” in Howe, Nature’s Mirror, 55-56.

[3] Ibid., 56.

[4] Howe, “Nature’s Mirror,” 23.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Labio, “‘Belgium is an Industrialist,’” 55.

[7] Ibid.

[8] See Walter Gibson, “Rustic Ruins,” in Pleasant Places: The Rustic Landscape from Bruegel to Ruisdael (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

[9] Ibid., 157.

[10] Michael Fried, Menzel’s Realism: Art and Embodiment in Nineteenth-Century Berlin (New Haven: Yale UP, 2002), 109.

[11] Stephen F. Eisenman, et al., Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History, 4th ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2011), 250.

[12] Labio, “‘Belgium is an Industrialist,’” 55.

[13] Eisenman, et al., Nineteenth Century Art, 250.

[14] Howe, “Nature’s Mirror,” 23.

[15] Labio, “‘Belgium is an Industrialist,’” 54.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Fried, Menzel’s Realism, 121.

[18] Labio, “‘Belgium is an Industrialist,’” 56.

[19] Christian Brinton, Constantin Meunier (Detroit: Redfield Brothers, 1914), 44.

[20] Labio, “‘Belgium is an Industrialist,’” 56.

[21] Melissa Dabakis, “Formulating the Ideal American Worker: Public Responses to Constantin Meunier’s 1913-1914 Exhibition of Labor Imagery,” The Public Historian, vol. 11, no. 4 (Autumn 1989): 117.

[22] Ibid., 132.

[23] Labio, “‘Belgium is an Industrialist,’” 57.