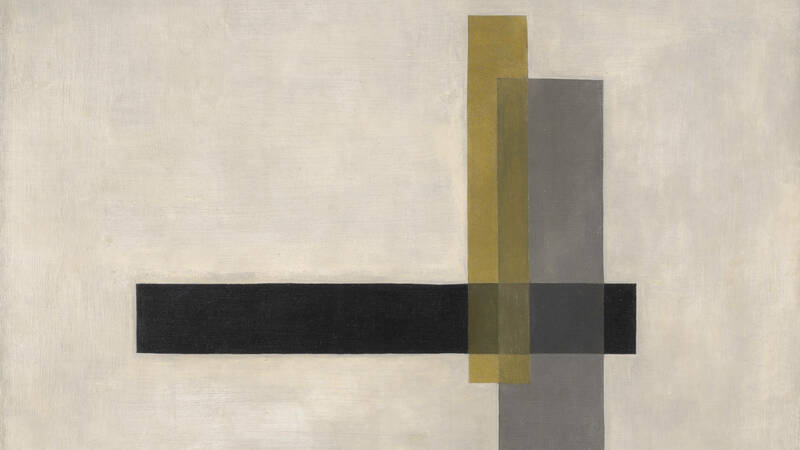

The Snite Museum's Composition (1923) (fig. 1) by László Moholy-Nagy, an early-career painting by the artist, represents a transcendence of the particulars of the medium in which it was produced. Although a work of oil on canvas, this piece indicates Moholy-Nagy's efforts to refute the constrictions painters had previously subscribed to—restrictions that Moholy-Nagy believed rendered their art unrelatable and removed from reality. In fact, considering that he and his wife began work in cameraless photograms in 1922, a year prior to the creation of Composition, the formal elements of this work suggest a cognizance more of the process of photography than of traditional painting. By drawing inspiration from this photographic work and from the constructivist movement, as well as the ideals of the Bauhaus school, Moholy-Nagy invigorated this painting with a sense of universality and modernity. Composition (1923) demonstrates an early attempt by Moholy-Nagy to translate the visual language of photography into painting, seen explicitly in his efforts to replicate the effects of light through pigment. In doing so, what he sacrificed in his representation of light he gained in abstraction and the construction of non-representational yet emotional scenes.

Throughout his career, Moholy-Nagy intertwined his life experiences into his art, rendering a basic knowledge of his background crucial to understanding Composition. Moholy-Nagy was born in 1895 in a small town in Hungary, which at the time was a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Despite, or perhaps because of, this provincial background, from a young age he had an interest in industry and modernity, and he departed rural Hungary at 19 to fight in World War I. After being injured and also traumatized from the violence of war, he left the army to become an artist in 1919. In his writings from the same year, it is evident that Moholy-Nagy was already considering the shortcomings of the art that preceded him. In a diary entry, he asked whether it was "right to become a painter in the time of social revolution." Moholy-Nagy answered his own question by noting that "art and reality have had nothing in common during the last 100 years. The personal satisfaction of creating art has added nothing to the happiness of the masses. [...] It is my gift to project my vitality, my building power, through light, color form. I can give life as a painter."[1] In "the last 100 years," Moholy-Nagy saw only examples of art removed from truthful human experience. In looking at the nationalistic Romantic works, idyllic landscapes, and idealized genre scenes in the representational art of the 19th century, Moholy-Nagy saw a world resigned to the past and removed from the present and future. Thus, from the outset of his career, he displayed a desire to create art not only aligned with modern technology, but art that also dealt with the expression of universal ideals rather than a particular reality.

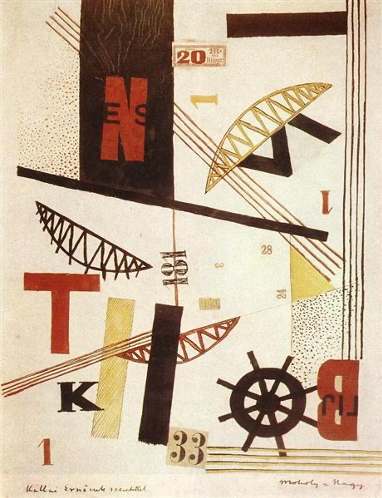

In the 1920s, Moholy-Nagy began to work in constructivism, a movement from the Soviet Union that emphasized finding an intersection between mechanical objects and art. This sought to make art more utilitarian, with designs that reflected the order and function of a new, more rational society. Pieces like Nickel Construction (1921) (fig. 2) show a borrowing of materials, forms, and techniques from industry and design. The metal sculpture, made of welded nickel-plated iron, brings together heavy, industrial pieces of metal with a delicate spiral. In doing so, it makes the case for the potential of mechanical objects to become art and vice versa.[2] Another piece from the same year, Hidak Bridges (1921) (fig. 3), further demonstrates an integration of forms from the world of modern industry. This work, inspired in part by the Dada collages of the post-war period, uses the repetition of the shape of a bridge to invoke the image of a rapidly industrializing society. The same theme of mechanization comes through in the rectilinear shapes of Composition. This piece, created slightly later than the two aforementioned, does not borrow the forms and materials of a construction site as explicitly, largely because Moholy-Nagy became increasingly committed to abstraction as his career unfolded. However, its strict lines and 90-degree angles, coupled with a muted, industrial color palette, certainly convey a sense of manufactured modernity.

Moholy-Nagy's involvement in constructivism introduced him to the Bauhaus school based in Weimar, Germany. The state-funded school had been founded in 1919 with a mission to reconcile art with craft. However, in 1922, director Walter Gropius became concerned with the Bauhaus's reliance on the tumultuous Weimar Republic, and believed that aligning itself instead with interests of modernism and industry would better justify the school's existence to the state and secure its economic future.[3] Gropius hired Moholy-Nagy to the Bauhaus as a faculty member in 1923.

During his time at the Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy began in earnest his pursuits in photography. More specifically, he worked in the medium of photograms, a cameraless technique that had been introduced to him in 1922. The process of creating a photogram involves exposing photosensitive paper to a light source. This produces a negative, in which areas hit by the light become dark and areas blocked from it remain white.[4] Considering that Moholy-Nagy was experimenting in photograms at the same time that he painted Composition, it is reasonable to assume that this work in photography influenced the painting.

Moholy-Nagy applied one aspect of his photography to Composition through a conflation of the respective media of photograms and painting. As a photographer first and foremost, even while working with oil on canvas, Moholy-Nagy believed that pigment was simply a tangible substitute for light.[5] This idea directs the construction of Composition, which, like many of Moholy-Nagy's other early paintings, contains what can be described as "overlapping shafts of light."[6] These "shafts" take form in the translucent yellow and gray rectangles, which appear to depict colored beams cast onto the canvas. However, these areas of the painting also confuse the eye with their variations in opacity. The rectangles appear opaque, independent of each other, adding a solidity that undermines the reading of them as fragile and intangible rays. Yet, when combined, they become semi-transparent, reinstating their luminosity. By creating this effect, Moholy-Nagy also forces the viewer to consider how the elements of the work are arranged and think about the mechanics of the piece in an abstract way. It is difficult to tell what order the shapes are in, or what plane each of them occupies. Because of the two-dimensionality of the space and the attempt at elimination of perspective, one can even question whether the forms are overlapping at all, or if the areas of perceived intersection are actually shapes of their own.[7] To create these areas, Moholy-Nagy did not simply blend the colors of the intersecting shapes together. Rather, he created unique pigment mixtures in order to better capture the effects of light, the material of his photograms, rather than of pigment.[8]

Another application of the influence of photograms comes from the idea of inversion. Although intuitively the painting appears to have a white background with three overlapping rectangles coming out of it, in a photogram the same white space would become a positive form and the black rectangle would be negative space. To further support this idea, one may note that the white area of the work is likely exposed canvas with a thin priming layer on it, in contrast with the rich pigments used in the rest of the piece. Though this lack of material seems to conflict with the idea of the white region as positive shape, in a photogram, light-colored regions are the result of an object blocking the paper from light. Thus, thinking of light as the medium for photography, white areas are the result of an absence of this medium. Moholy-Nagy himself articulated the way in which this could be translated to painting in 1921 by saying, "I became interested in painting-with-light, not on the surface of canvas, but directly in space. Painting transparencies was the start. I painted as if colored light was projected on a screen, and other colored lights superimposed over this."[9] Therefore, while this stand-in for "colored light" was allowed to leave its mark on the work in the colored regions, its absence in the white space further suggests it as the most solid portion of the piece. Much like how the shape of a flower constitutes the clear positive form and focal point of Flower (1925) (fig. 4), so too may the seemingly subsidiary unpainted region. With this idea working against initial assumptions, Moholy-Nagy's work captivates the viewer and causes them to question their approach to not only the painting, but the world around it as well.

Moholy-Nagy's choices with regard to the colors of this work can also be connected to his endeavors in photography. At the time Moholy-Nagy was creating Composition, it was unconventional to use the pure black seen in the horizontal rectangle, which is likely ivory black pigment. "'Clear black,' it was said, 'does not exist in nature. It has to be produced from red, green and blue.'"[10] Moholy-Nagy, working in a strict non-representational by this time, ignored this tradition to create a dissociation with the natural world. In addition, the deep black hue also evokes the color palette of a photogram, in which pure black is contrasted with white and gray tones, much like the black in this work is set against the lighter gray, yellow, and white.

A further element of Composition that implies an association with Moholy-Nagy's photography is the lack of a signature, a departure from some of his other works. Based on the works in the exhibition Moholy-Nagy Nagy: Future-Present (2016), it appears that Moholy-Nagy signed his non-photographic works fairly consistently until around 1921, in which he began dispensing signatures more sparingly.[11] After this year, though many of the works on media other than canvas still bear Moholy-Nagy's autograph, paintings on canvas such as Composition generally do not. However, it must be noted that none of the artist's photograms from any point in his career are signed. As in his other works of canvas, it seems that Moholy-Nagy intentionally dispelled the use of a signature in Composition in order to further dissociate the work from its medium, especially considering that a key difference between painting and photography is the direct contact with the subject matter necessitated by the former. This concept relates to Moholy-Nagy's desire for "painting-with-light," a phrase that implies a prioritization of the artist's mental process over the work of the hand—a common trope associated with photography. By combining the absence of his name with the lack of any visible brushstrokes, Moholy-Nagy distanced the artist's hand from his art, a topic he discussed himself in writing:

I was not afraid of losing the "personal touch" so highly valued in previous painting. On the contrary, I even gave up signing my paintings. I put numbers and letters with the necessary data on the back of the canvas, as if they were cars, airplanes, or other industrial products. [...] My photographic experience, especially photograms, helped to convince me that the complete mechanization of technics may not constitute a menace to essential creativeness.[12]

The connection between art and "industrial products" suggests a diminishing importance of the artist's identity with reference to their work, which adds a universal feel to Moholy-Nagy's art. It also demonstrates an alignment of the interests of the Bauhaus, the environment in which Moholy-Nagy created the majority of his photograms. Within this context, Composition clearly reflects the idea of "mechanization" as it relates to photography. The geometric nature of the work, complete with strict lines and angles and a balanced composition, makes the painting seem almost manufactured, as if it were factory-made. This connection to manufacturing also implies the potential for mass production, a concept that became connected with art through the reproducibility of photography.

These formal elements and the association with technology allow Composition to feel firmly implanted in the notion of the modern. However, it is not the harsh view of modernity that one might expect from a post-war context. The painting's association with light adds a softness and presents an unexpectedly optimistic view of the rapidly-changing environment in which it was produced. From this idea arises a paradox within Moholy-Nagy's oeuvre, especially with regards to his paintings on canvas. As an artist in the early 20th century, Moholy-Nagy was fairly unique in his embrace of the union between industry and art. Even after the horrors of World War I, an event that caused many artists to feel apprehensive of technology and its capacity for destruction, Moholy-Nagy remained more suspicious of representational art's failure to capture reality than of industry. Thus, to fully understand a work such as Composition, a viewer needs a certain level of knowledge of Moholy-Nagy's outlook on life, as well as of the circumstances of the time period in which he was working. Yet, Moholy-Nagy also sought to diminish any associations of his art to a particular reality in order to retain its universality; his conscious efforts to remove any traces of his own hand reflects this idea. The only way to reconcile these two seemingly competing ideas in Composition is by reading the painting using the language of photography. The validity of this reading is reinforced by the formal elements highlighted previously—namely the colors, distribution of pigment, replication of light, geometric shapes, and lack of signature. With these aspects of the work in mind, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy constructed in Composition a non-representational scene that forces the viewer to confront and challenge their own ways of seeing. Encompassed in the work's abstraction is a potential for individuals to extract a personal meaning from the piece, but the universal quality of the painting makes it so that every viewer approaches it on equal footing, with no one person better primed to connect with it than the next. And, because of its association with the technological innovation of Moholy-Nagy's photograms, Composition presents an optimistic view of modernity that does not cast out emotional expression, but rather literally brings it to light.

[1] Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Moholy-Nagy: Experiment in Totality (New York: Harper Publishing, 1950), 12.

[2] Matthew S. Witkovsky, Carol S. Eliel, and Karole Vail, eds., Moholy-Nagy: Future Present (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017), 152.

[3] Joyce Tsai, László Moholy-Nagy: Painting after Photography, vol. 6, The Phillips Collection (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 29.

[4] Julie Barten, Sylvie Pénichon, and Carol Stringari, "The Materialization of Light" in Witkovsky, Eliel, and Vail, eds., Moholy-Nagy, 188.

[5] Johanna Salant, Julie Barten, Francesca Casadio, Maria Kokkori, Federica Pozzi, Carol Stringari, Ken Sutherland, Marc Walton, "László Moholy-Nagy's Painting Materials: From Substance to Light," Leonardo 50, no. 3 (2017): 318.

[6] Barten, Pénichon, and Stringari, "The Materialization of Light," 193.

[7] László Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision and Abstract of an Artist (New York: Wittenborn, Schultz, Inc., 1928), 71.

[8] Salant et al, "László Moholy-Nagy's Painting Materials," 318.

[9] Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision, 75.

[10] Ibid., 72.

[11] Witkovsky, Eliel, and Vail, eds., Moholy-Nagy, 193.

[12] Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo. The New Vision and Abstract of an Artist. 79.