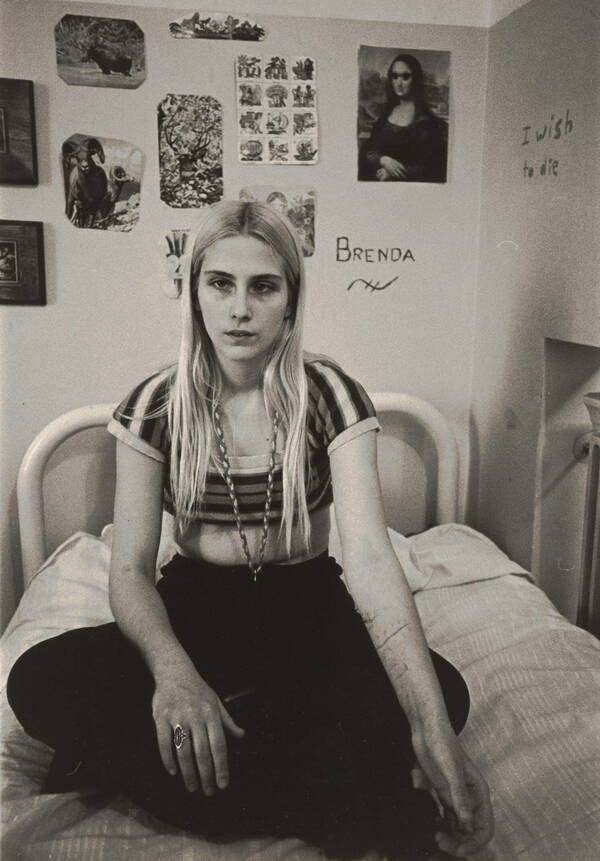

Recently, the movement to end the stigmas around mental health has become one of the most popular across the entire world, especially with the rise of social media and the subsequent normalization of publicly sharing personal aspects of one’s life. The photo Brenda Sitting on Her Bed, Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, 1976 (which will hereby be referred to as Brenda Sitting on Her Bed), captured by photographer Mary Ellen Mark, contributes to this movement by providing an empathetic gateway into the life of a seriously ill, yet still relatable, young woman. At first glance, the photo appears to be a casual snapshot of a normal teenage girl, but viewers are left unsettled and curious after observing closer. Mark’s complex representation of Brenda not only demonstrates strong rhetorical choices, but also produces a space for this significant contemporary discussion. These qualities enable Mark “to persuade, to inform, to learn, [and] to achieve consensus” (“What We Teach”)—the goals of the Notre Dame writing program—with her readers about the value of including mental wellness in this modern global conversation about health. Brenda Sitting on Her Bed deserves a prominent place within the curriculum of future Writing & Rhetoric courses at the University of Notre Dame because the photograph sparks a conversation about mental health, aligns with the program’s learning goals, and evokes strong emotions.

Brenda Sitting on Her Bed elicits a discussion of mental health that historically has been overlooked or misrepresented. Although the societal conversations regarding mental wellness often “emphasize violence, dangerousness and criminality” (Cutcliffe 317), Mark’s photo does the opposite, instead encouraging her viewers to look at mental illness as an issue that affects them and their loved ones.

A stark contrast to Brenda’s trendy clothing and sunglassed Mona Lisa is one particular phrase Brenda has written on the wall: “I wish to die.” Since the writing is on the side of the photograph, it becomes a bit of an afterthought to the viewer, which allows them to initially see Brenda as a young woman they can understand, rather than just another unstable patient in a locked ward. In doing this, Mark breaks down the “sense of ‘them and us’” (Cutcliffe 319), so common in depictions of mentally ill people. Through Brenda Sitting on Her Bed, Mark creates an image that forces the viewer to address the stereotypes surrounding mental illnesses. Mark reminds her audience that suicidal people are not “others” or some distant concept. Brenda Sitting on Her Bed encourages further discussion and dialogue about the content of the photo and its meaning, which is exactly what the Writing & Rhetoric courses at the University of Notre Dame aim to do through their assignments on rhetorical evaluations of a visual text.

Furthermore, Brenda Sitting on Her Bed aligns with other goals of the University of Notre Dame’s writing program. The goal of the program is to teach students how to form “a relationship between writer and reader, speaker and listener” (“What We Teach”) through their work. Mary Ellen Mark’s photo does exactly this. By allowing the viewer to enter into Brenda’s most private area of her life, we are allowed a glimpse into who she is and the story that has led her to the captured scene. The viewer understands some of Brenda: her style, her pain, her sense of humor, her suffering. When the audience is given just some information, they crave to know more. It is in this sense that the relationship between the viewers and Brenda forms, which is the ultimate goal of the University’s writing program. Unlike the program’s goal of establishing relationships between “writer and reader,” this relationship does not form between Mary Ellen Mark and her audience; the audience connects not to Mark, but mostly to Brenda. This relationship further demonstrates how photographic framing “encourages viewer awareness of the linkage between seeing and knowing” (Lancioni 105), as it allows the viewer to understand that there is much more to learn about Brenda beyond what they can observe or begin to understand in this single photo. By removing the photographer’s presence from the photograph, the conversation around mental health and suicide returns its power to those who are actively fighting those struggles every day. The writing program at Notre Dame also seeks to give its students the tools to create arguments that ask “those questions moral philosophers have for centuries regarded as ethical” (“What We Teach”). The discomfort brought by this photo leaves the viewers wondering if the taking of the photo itself is ethical, or a breach of Brenda’s privacy. The audience questions if, in her current mental state, Brenda was able to consent to the public display of her very private image. Perhaps they even consider the ethics of keeping patients in a locked ward altogether. Overall, Brenda Sitting on Her Bed forms a relationship with its audience and creates a greater discussion both of health and of the power of rhetoric.

Additionally, Brenda Sitting on Her Bed calls for an emotional and curious reaction from its viewers. The audience initially feels drawn into this image when they see a normal-looking and relatable young woman, dressed in a trendy top and surrounded by light-hearted decor. Maybe it takes some viewers a few moments to process that Brenda’s body is captured in such a way that her scars from cutting are showcased. The initial relatability of the image is somewhat stripped as the audience takes in its more serious and sad aspects. This immediate connection, although not fully representative of Brenda, results in the audience’s empathy towards her. The stark contrast between seemingly understanding Brenda as a normal teenage girl and then as a tormented patient in a psychiatric ward leads viewers to “question the relationship between the parts of the photograph and the whole” (Lancioni 108). While parts of this photograph are either quite average or shockingly despondent, the whole image combines these differing elements to allow the audience to understand Brenda in her complexity. As Sturken and Cartwright say in their “Practices of Looking,” the power of an image derives from its “evocation of the emotions of life’s struggles” (Sturken and Cartwright 19). Brenda Sitting on Her Bed is incredibly powerful because it captures evidence of Brenda’s struggles, which elicits the audience’s emotional response. The University should incorporate this photo into Writing & Rhetoric course plans so students can engage in a rhetorical analysis of this text while also analyzing a contemporary issue close to the students’ personal experiences.

One potential issue with the public showing and required completion of an assignment focusing on Brenda Sitting on Her Bed is that its graphic elements, such as Brenda’s self-harm scars on her inner wrist, could be quite triggering. Many students at Notre Dame either have struggled with or actively struggle with poor mental health and self-harm. Because of this, some students and administrators would urge the University to avoid showing this image to students. A lot of these possible critics value the importance of classroom settings as safe spaces, but it is important to note that the University is also called to “offer more than a refuge that merely shields a learner” (Gunn) and therefore promote course content that could be uncomfortable for the sake of deeper learning. Making this photo of Brenda an integral part of the curriculum provides Notre Dame with a unique opportunity to get ahead of the conversation around sensitive content in academia. Notre Dame can use this photo and the complex scenario it produces in the classroom to acknowledge what can re-traumatize students, and then provide a secondary assignment for students who do not wish to spend a significant amount of time and thought analyzing Brenda Sitting on Her Bed. Including this photo of Brenda in future Writing & Rhetoric courses gives the University a head-start on incorporating trigger awareness into all of their departments. Triggers will not go away, but the stigma of weakness surrounding them can. Notre Dame has the opportunity to lead as an institution by offering students both a perhaps traumatizing image and a safer, less upsetting alternative for this assignment. Using Brenda Sitting on Her Bed in Writing & Rhetoric courses will spark new conversations about mental health and the validity of trigger awareness and accommodations. The University of Notre Dame needs to accommodate students with past or current trauma, and a great way to start is by immediately implementing Brenda Sitting on Her Bed and a sensitive alternative into the Writing & Rhetoric curriculum.

In conclusion, Brenda Sitting on Her Bed, Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, 1976 by Mary Ellen Mark should be included in the course plan for future Writing & Rhetoric classes at the University of Notre Dame. Brenda Sitting on Her Bed is a photo that could be more graphic than any others that students have previously studied, which encourages them to understand the emotions and discomfort that can arise as an effect of powerful texts. Brenda Sitting on Her Bed teaches students the importance of strong rhetorical choices in photography, while also summoning a compassionate response to Brenda’s struggles. If added to the Writing and Rhetoric curriculum, Brenda Sitting on Her Bed, Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, 1976 will ensure that no student’s “mind will be cultivated at the expense of the heart” (“University Mission and Vision”)—just as the University’s founder intended.

Works Cited

Cutcliffe, J. R., and B. Hannigan. “Mass Media, ‘Monsters’ and Mental Health Clients: the Need for Increased Lobbying.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, vol. 8, no. 4, 2001, pp. 315–321, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00394.x.

Gunn, Jennifer. “History & Importance of Safe Spaces in Schools: Resilient Educator.” ResilientEducator.com, 16 Jan. 2019, resilienteducator.com/classroom-resources/creating-safe-spaces/.

Lancioni, Judith. “The Rhetoric of the Frame: Revisioning Archival Photographs in the Civil War.” Western Journal of Communications, vol. 60, no. 4, 1996, pp. 397-414, doi: 10.1080/10570319609374556.

Mark, Mary Ellen. Brenda Sitting on Her Bed, Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, 1976.

Sturken, Marita, and Lisa Cartwright. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford University Press, 2018.

“University Mission and Vision.” Du Lac: A Guide to Student Life, 2020, dulac.nd.edu/university-mission-and-vision/.

“What We Teach.” What We Teach // University Writing Program // University of Notre Dame, 2020, uwp.nd.edu/about-the-program/what-we-teach/.

Discussion Questions

-

The genre of evaluation requires agreement about particular criteria that are of importance to both the evaluator and the intended audience for the evaluation. Underline the criteria that this student writer uses as major points of evaluation. To what extent do these criteria reflect values of the student writer’s audience? Which audiences might select different criteria on which to base their evaluation?

-

Where and how does the student writer address counterclaims, or possible objections, in this essay? How does the writer demonstrate the legitimacy of her readers’ concerns about the text being evaluated?