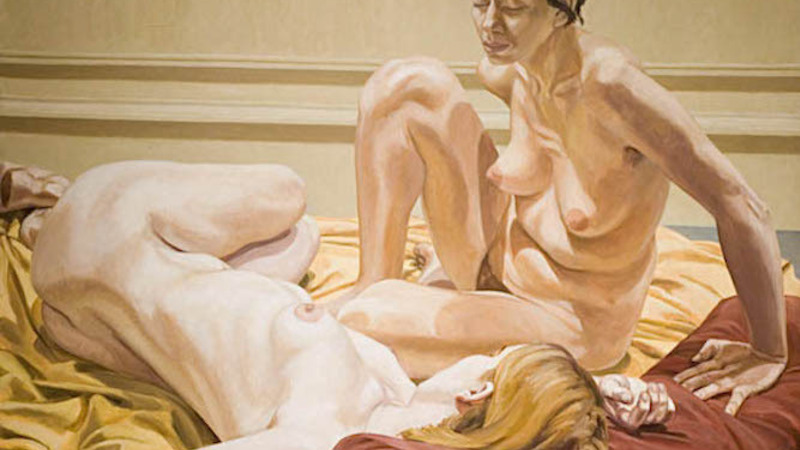

It was the week that Notre Dame began seriously considering banning pornography on campus that I first saw "Two Female Nudes on Yellow Drape." Of the friends I mentioned it to, all said something along the lines of "yikes," and "yikes, that one," and "yikes, that one made me uncomfortable, and startled me in a very unsettling way." This mystified me a little bit, but I understood. Yes, there are nipples and thick thighs and stomach rolls, but there's also a great and beautiful serenity that should be so much more important than any shock value. At the same time, however, there is something slightly off about the ensemble, and it took me a little while to realize what exactly that was.

I almost didn't see it. Had I chosen to go upstairs a different way, I would have missed its pastel-hued allure. All other paintings, sculptures, furniture, and decorative objects in the Snite are on full display in what are obviously gallery spaces; Philip Pearlstein's vast, gently erotic painting is not. Hidden away in a stairwell— whether isolation for censorship or isolation for accentuation, it is impossible to tell— it surprises you. Shocks you, even, because it's not the sort of image you expect to find on this campus.

You ascend the stair to the second level, past staff offices, past the tiny windows that look out to the campus just beyond ivy and bricks, looking at your feet, until you aren't looking at your feet because suddenly, right there, right in front of you, are soft shadows on soft skin, bare bodies offsetting bare walls, and a genuinely palpable tenderness. One wonders, then, why this painting is displayed less prominently than the first-floor water fountain.

Never has so much nakedness conveyed so much comfort. It is felt innately that the temperature in their room is perfect, that the light is perfect, that whatever surface they are on is perfectly soft, and that they are perfectly alone. It is far too easy to see sensuality as the only genre of emotion that can ever apply to a nude portrait, but far from forcing lust onto its viewer or serving as a vehicle for youthful bodies, this painting has nothing but calm warmly emanating from its frame.

The women are casually, unflinchingly bare. At peace with themselves and with each other, they do not shy away from letting their imperfect, aging bodies ease into organic shapes. All muscles are relaxed. One woman sits, her shoulders rounded, her legs repositioning themselves. The other lies on her side, one hand's fingers so loose that she seems asleep. The titular yellow drape lies beneath them, as soft and aged as the women themselves; though it could easily cover both, they have chosen not to conceal themselves. They can see everything, and don't seem to mind. You can see everything too, and can choose not to let yourself mind either. Moving past shallow discomfort, you can instead notice the more important things: a deep red cushion lying to the side— one that they have clearly been sharing.

You can notice that these two women love each other. Whether or not they are lovers is irrelevant— there is a depth of trust and comfort between them that is unique to only the most genuine love. The woman towards the back seems as though she has just raised herself into a sitting position, legs splayed unabashedly. In that liminal place between sleeping and facing the world, anything can seem natural. Her eyes are ambiguously either slightly open or slightly closed, as if she has woken up naturally within a moment of the painter rendering her. Maybe she's gazing into the other woman's eyes. Maybe the other woman, whose eyes we cannot see, is returning her gaze. Maybe not. You don't need to know, and it's better if you don't. Every great painting has a mystery. If we knew why the Mona Lisa was smiling, she wouldn't have the same sly, haunting beauty.

Unfortunately, my time spent staring at the painting was marred by a nagging thought in the back of my head: the painter saw everything that I could see. In fact, the painter chose these people, in this state of nakedness, in these poses. He certainly did not choose the youngest possible models, or the most beautiful— maybe he wanted something beautiful in their relationship instead. A difficult question arises: can we ever really know if an artist (and, historically, especially a male artist) chooses to depict bare bodies for himself, or for the art? And, further, to what degree can and should art be separate from lust?

There is a strange and somewhat perverse relationship between painter and model, particularly when it comes to nude portraits. An artist uses the grandiose phrase "fine art" as a reason to tell people what to do with their bodies… to make them stay still while (s)he looks at them for a prolonged period of time, following lines and analyzing contours. Similarly, there is a strange and somewhat perverse beauty in how many boundaries can be broken for art.

It is dangerous to use art as an excuse for the breaking of boundaries, yet this has given us some of the greatest art of all time; in fact, we love to think that in order to make great art, artists must have great (and troubled) passion. Indeed, most brilliant writers seem to have had a well of tragic pasts to draw from. Most genius songwriters have been spurned by lovers. Picasso— who we unflinchingly call a master of canvas and sculpture— cruelly treated his models as objects of desire, but channeled this sexual fervor into undeniable masterpieces. The multiple suicides resulting from his mistreatment, though perhaps they should, do not change the art itself, and for the most part do not change how it is viewed.

Ultimately, our new question becomes this: can we consider art by itself, from a purely aesthetic standpoint, separate from its creator? We certainly do this with many other creative forms. Authors who cheat on their spouses are lauded tragic geniuses who can't help themselves. The works of Frank Lloyd Wright are revered to this day, despite his mistreatment of his family. Wagner is lionized for his masterful compositions, but not for his anti-semitism, though he possessed both. Harvey Weinstein, who produced several esteemed films, sexually abused a whole series of women throughout his career.

To some degree, it is ridiculous to look so far into the past at a long-dead creator when his/her art is still with us. But this implies that after a certain passage of time, human issues fade while artistic merit lives on, and further that the latter of these is far more important than the former. There is a burdensome tradeoff here; a choice which should be easy, but which is not. In ignoring a work of art's unfortunate past, we do a disservice to the people who suffered at the hands of temperamental geniuses. In focusing on said past, we do a disservice to the art itself.

We have a duty to forget for the sake of art, but also a duty to remember for the sake of human dignity. Choosing between those two will never be easy, or even possible, but compromise is essential. Even if all I want to see is quiet desire, subtle passion, and deep tenderness, I will always feel Philip Pearlstein seeing with me. Maybe we see the same things, and maybe we don't, but I'll never know one way or the other. In a simpler world, these things are kept hidden in stairwells; in this world, regardless of what type of forgetting accompanies it, we have a duty to view great art from all its angles.

Discussion Questions

- The author uses their own embodied experience in the Snite to situate and develop their argument and perspective. How does this maneuver establish ethos and what kind of ethos would you say the author has established?

- Towards the middle of the essay, the author shifts from the first person perspective to the second person. How did this make you feel? What does this shift demand of you, the reader?

- While this piece is ostensibly an analysis of a work of art, it brings up numerous topical and perennial issues. Make a list of the issues raised in this piece and determine exactly how the author's analysis of the work of art illuminate her position on these issues.