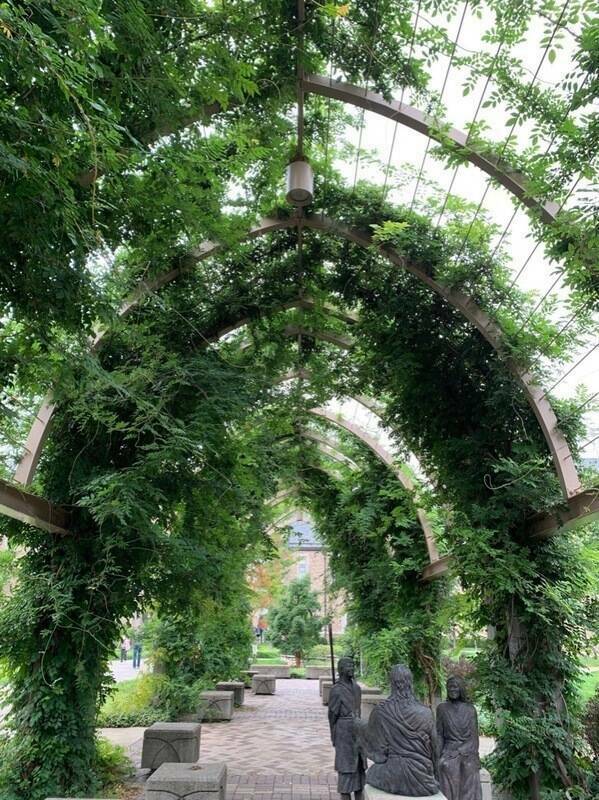

When students, faculty, staff, and visitors walk through the University of Notre Dame, it’s hard to miss the vast number of outdoor common spaces we have. However, one of these spaces between the always busy DeBartolo Quad, Fitzpatrick Hall of Engineering, and Law School stands out. The Sesquicentennial Common, constructed in October 1992, consists of concrete columns rising into a metal beam laced with wireframing to form an open vault extending East and West.

These somewhat sterile materials are then draped in vines, bushes, flowers, and other vegetation, creating a compact little greenspace in one of the busiest parts of campus. Walking through its groin vault entrances, one is greeted by a simple arrangement: brick flooring, concrete slabs for seats, lights in the ceiling for the night. Occupying two of those seats is Christ the Teacher by Burl Jones. This statue, dedicated in 2004 by Robert and Louis Tabit, depicts Jesus sitting on a concrete slab, teaching two young students under the green canopy of the structure. All of these features combine to create a little refuge on this ever-busy college campus. But while the Sesquicentennial Common is used by students, faculty, staff, and visitors as a nice place to relax, it’s overlooked how the space reflects Father Edward Sorin’s image for the University of Notre Dame Du Lac through its nature, educational implications, and religious connections.

Some of the more introspective may ask: “Doesn’t the entirety of campus as we see it today demonstrate Father Sorin’s image for the University of Notre Dame?” Indeed, our ever-expanding campus only adds to and fortifies the values and goals he set for this school. The Hesburgh Library allows students a place to study and learn more efficiently, DeBartolo creates space for more classes to be held for larger student bodies, and Notre Dame Stadium lets us come together as a community. But while it may be true that the modern builds upon Father Sorin’s image of ultimate good, the green canopy shielding Christ the Teacher and the seats surrounding it truly call back to the ambiance and vision in the head of Father Sorin when he began to build the university.

When Father Sorin arrived at the allotted plot of land that was soon to become Notre Dame, he had just come off a torturous and miserable journey in the cold. Yet even with the bitter winter, Father Sorin was able to see the beauty of the land: “Everything was frozen, and yet it all appeared so beautiful. The lake, particularly, with its mantle of snow, resplendent in its whiteness, was to us a symbol of the stainless purity of Our August Lady, whose name it bears; and also of the purity of soul which should characterize the new inhabitants of these beautiful shores” (Moreau 260). Luckily for Father Sorin, he had the opportunity to build one of the greatest universities in the world on this scenic plot of land. In the early years of the university, when the campus consisted only of some log cabins adjacent to the lake, life was very much integrated with the natural beauty of the land. In The Chronicles of Notre Dame Du Lac, Father Edward Sorin described the second colony’s first impressions when landing at Notre Dame in 1843 as: “This moment may serve as a point of comparison to represent to themselves what they will one day experience when they meet in heaven” (Sorin 33).

Today, campus is still full of sprawling vegetation and trees; the lakes remain adorned with plants along the walkways, and precise landscaping makes everything visually appealing. However, not only is this man-made nature, but you’re certainly not able to interact with it from a lecture in DeBartolo. This is why the space surrounding Christ The Teacher is so unique. When sitting and studying there, one is encompassed by nature and vegetation on all sides. This fusion of nature and education calls back to the way of life Father Sorin and students experienced in those initial years at Notre Dame.

Physically, the Sesquicentennial Common lies on what is today one of the most academically dense and busiest areas on campus. DeBartolo Quad has buildings such as Fitzpatrick Hall of Engineering, The Law School, Stinson-Remick Hall of Engineering, DeBartolo Hall, DeBartolo Performing Arts Center, and Mendoza College of Business, just to name a few. When traversing DeBartolo Quad, it’s easy to notice how all these buildings look fairly similar. Notre Dame makes a point to maintain consistency in the architecture of campus: pale brick, gothic elements, timeless designs. In doing so, they not only create a sense of cohesion and community but also achieve affect theory across campus. Affect theory “describes the psychology of emotions that are prompted by images or words. Our memories of similar images combine with the present image in order for an image to have an effect on our emotional state” (Helmers 6). In the Sesquicentennial Common, we can see elements from the Basilica of the Sacred Heart echoed.

Both structures show gothic elements with their pointed arches and groin vaults. Through affect theory, this connects the common area not only even more to the Catholic faith but also to the history of the university. The university’s first church of the Sacred Heart was constructed in December of 1842. Father Sorin believed it imperative that there be a church to worship for Christmas that year and would stop at no expense: “In three weeks, trees enough were cut down and hauled to the place to put up a building forty-six feet by twenty. On the day appointed, the men assembled and raised the walls of the new temple. The efforts of their liberality did not go beyond that. Fr. Sorin had to have the building finished at his own cost, otherwise, no church would have been there for years." (Sorin, et al. 31) At a time when absolutely nothing was guaranteed for the university, especially not financial success, Father Sorin spent out of his own pocket to guarantee that faith could be practiced. Today, with the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, the third main church on campus, and chapels in every dorm, spirituality is easier than ever to practice. However, Father Sorin saw faith as only half the equation to the success of Notre Dame. This is why the Sesquicentennial Common’s location on DeBartolo Quad is so important. All who walk through the academic quad, whether from class or on a stroll are reminded of the university’s faith through the Commons’ and Basilica’s shared architecture. However, if one doesn’t consciously notice what their subconscious might about the Sesquicentennial Common’s architectural significance, there is a more direct reminder of the space’s religious significance.

Towards the center of the Sesquicentennial Common lies Christ the Teacher by Burl Jones. This statue shows Jesus Christ sitting down in the common area of the enclosure and teaching two young students. And this isn’t some grandiose statue towering over those who just want to relax and study in the space, but rather an integration with the area.

The scene only takes the space of two chairs, but even more importantly Jesus and his students are seated on the same concrete slabs that anyone sitting there would use. This serves as a physical demonstration of Father Sorin’s ideology that Jesus and religion should be with students as they navigate their studies at Notre Dame. In his letters to Father Moreau, Father Sorin always expressed how he foresaw this university as an ultimate means of doing good in this country. But when writing to the brothers and sisters of the University, Father Sorin goes further in-depth: “When I consider, in the presence of God and of our Lord Jesus Christ, the immense good which may be done, the multitude of souls that may be saved from eternal destruction if we are faithful to our holy call, while it fills my heart with an unspeakable admiration and gratitude” (Moreau 265). Father Sorin not only foresaw that students can become doers of good in this world, but that they can also practice religion to find eternal life after death as the result of a Notre Dame education. This hand in hand nature of education and religion that Father Sorin built is reflected today in the university’s mission statement: “As a Catholic university, one of its distinctive goals is to provide a forum where, through free inquiry and open discussion, the various lines of Catholic thought may intersect with all the forms of knowledge found in the arts, sciences, professions, and every other area of human scholarship and creativity” (University). We’re able to see how Father Sorin’s Catholic principles are ingrained even today into our curriculum. Therefore, when Christ The Teacher and the Sesquicentennial Common combine to publicly display that foundational connection between school and God, it reflects Father Sorin’s aspirations for the educational and spiritual good that Notre Dame could, and clearly would go on to, achieve.

The Sesquicentennial Common shows how a simple structure can represent and embody so much. The precision and dedication to invoke such momentous themes and feelings are astounding. The university may tell an architect what they want, but it is up to the architect to figure out how to properly integrate those elements. In his book Architecture: A Very Short Introduction, Andrew Ballantyne states: “What architects do is to design buildings with an eye not only to their practical utility but also with an eye to their cultural value” (Ballantyne 4). Architects draw these historical and spiritual elements to adapt their works to a populace much like a writer does to their audience. However, they can only guess and estimate how the public will respond so well. The Sesquicentennial Common’s construction may have resulted in an expected use case. However, installations like “Touchdown Jesus” or “First Down Moses” certainly picked up their own representations separate from the artist’s initial intentions. That’s the tricky aspect of designing and constructing not only a space but a rhetorical space. An audience will either embrace the work, reject it, or embrace it with a different meaning. For example, our connection with the Sesquicentennial Common wouldn’t be replicated if the space was placed at the University of Michigan. Through studying the various successes of works, the failures of others, and the rebirth of some, we may inch closer to perfecting the art of persuasive rhetorical spaces.

Works Cited

Ballantyne, Andrew, 'Buildings have meaning' in Architecture: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2002; online edn, Very Short Introductions online, Sept. 2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/actr..., accessed 11 Oct. 2021.

Dubroff, Don. “Basilica of the Sacred Heart, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN .” Conrad Schmidt Studios Inc., 7 Mar. 2010, https://conradschmitt.com/proj.... Accessed 6 Oct. 2021.

Helmers, Marguerite H. “The Elements of Critical Viewing.” The Elements of Visual Analysis, Pearson Longman, New York, 2006.

Moreau, Basile-Antoine-Marie, and Edward F Sorin. “Part Second.” Circular Letters, Ave Maria Press, Notre Dame, IN, 1943, pp. 259–265.

Shields, Miss J. “A Photo of Christ The Teacher by Burl Jones.” Twitter, 19 July 2021, https://twitter.com/MissJShiel.... Accessed 11 Oct. 2021.

Sorin, Edward, et al. Chronicles of Notre Dame Du Lac. University of Notre Dame Press, 2001.

University Communications | University of Notre Dame. “Mission.” University of Notre Dame, https://www.nd.edu/about/missi....