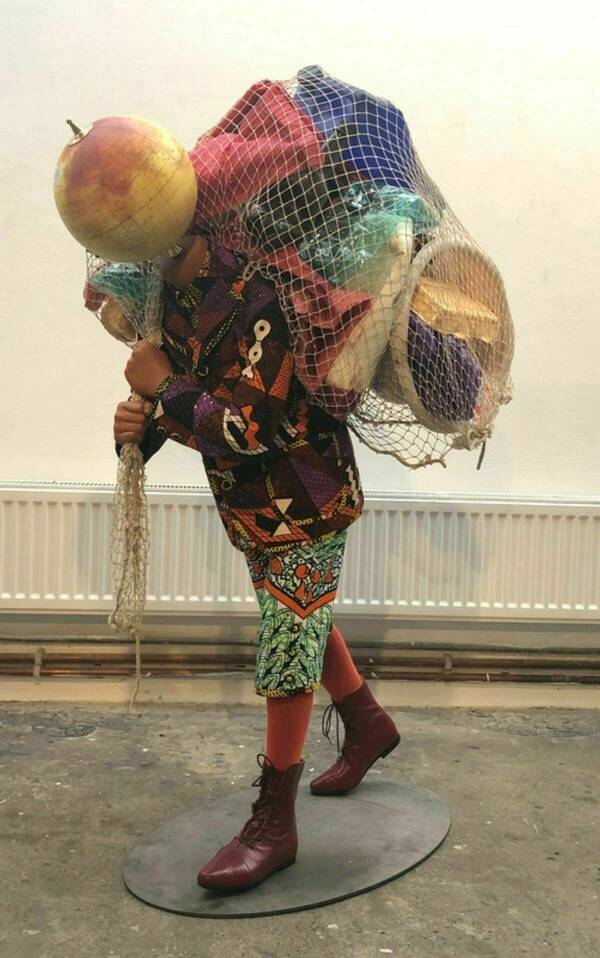

Nestled away in the corner of the Snite Museum of Art, a small figure bends over in anguish. Unless you need to pack your things away in the coatroom, it is easy to walk past the exhibition. At first glance, the sculpture is overwhelming. The loud colors of the boy’s patchwork clothes cause your eyes to plead for something less distracting to lay upon. It is an unsuccessful journey; the destination of your eye’s frantic scan is faced with a mountainous net of trash. After the scale of the sculpture is processed, the viewer realizes that the net is supported by a meager figure. The fragility of the boy’s physical appearance is contrasted by his disposition. The boy looks determined, yet tired, as the globe head tilts down and his grip tightens around the net. After a full breath of the piece is finally exhaled, a second look reveals additional visual clarity. The clothes are dissonant with clashing color and style. The African-style blazer has bright orange and purple textile, yet the knee-length shorts are patterned with vibrant, green leaves. Orange tights hide the legs, and glossy, red boots finish the look. The sculpture looks withdrawn, but its aura is not as compacted as its stature. Caught in a static state, his walk is interrupted by your gaze, and the boy is crushed under the weight of his trash.

That was my first interaction with Yinka Shonibare’s Earth Kid (Boy) (2020). Recently relocated from its temporary display in the Scholtz Family Works on Paper Gallery, the small figure took its place as a new centerpiece in the Milly & Fritz Kaeser Meštrović Studio Gallery of African Art. Earth Kid (Boy) reaches out from the exhibition to face the viewer in a low walk. With the recent unveiling of the Who Do We Say We Are? Irish Art 1922 | 2022 exhibit, visitors to the Snite Museum take a hard left at the atrium and miss the boy’s advances. Luckily, I was guided through an analysis of the sculpture when it still resided at the Scholtz Family Works on Paper Gallery. Although it was a gray Wednesday morning threatened by a downpour of rain, I reaped the benefits of a mind just awakening to reality. Unburdened by the stress of the coming day, I grasped the multi-layered aspects of Shonibare’s work with the same focus demanded by the intimate space. While my initial introduction to the piece took less than an hour, I spent months framing and reframing my own interpretation, and I found that Shonibare speaks volumes about the multitude of struggles faced by humanity with a single, meek sculpture.

The boy is the narrative focal point of this piece; however, it is impossible to ignore the personality of the trash. It feels as if the fishing net barely contains the boy’s burden. A diversity of items—from rubber gloves and bubble wrap to pacifiers and Styrofoam takeout containers—congeal into an indistinguishable mass at a distance. While these items are lightweight, the burden of ecological ruin is the symbolic explanation as to why the boy feels the crushing weight of the fishing net. The geometrical composition can be simplified as such: a small, broken shape struggling to keep a towering mass from swallowing him whole.

On one hand, the boy symbolizes the next generation’s growing responsibility in efforts to combat climate change. It is clear that today’s youth will need to aid in environmental recovery, but the real question is where the responsibility should lie. Although represented by a single figure, the globe head shows that climate change is a universal issue, not an individual one. On a global scale, individual action feels futile. However, the boy continues on his path resolutely in spite of his burden. Shonibare reminds his viewers that the burden of climate change will be an unavoidable weight on the shoulders of future generations, but the feeling of hopelessness can be combated with a global sharing of this responsibility.

The descriptive placard of the sculpture reads that Shonibare displays themes of colonialism in his art as well. Visually, the boy’s clothes are dissonant because they represent the fragmented identity of postcolonial nations. The Dutch batik cloth, also known as Ankara fabric, exposes the complex relationship of Shonibare’s own British-Nigerian ethnicity, which translates to the larger connection between Europe and Africa. Postcolonial nations struggle to identify in a country that has been mutilated by decades of erasure and shame. Shonibare focuses on themes of race and ethnicity further by creating an unidentifiable ethnicity for the boy, amplifying the fact that postcolonial nations share a similar experience of confusion and uncertainty.

An environmentalist lens reveals the relationship between postcolonialism and climate change as well. Postcolonial countries experience disproportionate effects of climate change because they do not have the same luxury to ignore its destruction. The fact that it is difficult to pinpoint an exact ethnic group makes the piece more perceptive to a developed country’s view. While the viewer is able to see severe droughts, floods, forest fires, starvation, earthquakes, and devastation in pictures, there are real people living with the consequences of an outsourced industrial economy that many countries utilize. Maybe the boy is gathering up debris from a flood? Maybe he is displaced because of a drought or a fire? Or, in an optimistic perspective, maybe he is simply clearing pollution out of his own self-willed responsibility? Shonibare asks his viewers these subjective questions, leaving them to ponder what caused this boy to be in his situation. The story of the boy has a destination, but we are stuck with a snapshot of the journey.

Earth Kid (Boy) masterfully weaves together multiple themes of life in the twenty-first century: how humanity depicts and interacts with climate change, how post-colonial nations struggle with more than just defining their identity, and how developed countries can live comfortably with climate change while developing countries live in their destructive wake. The message of Shonibare and other societal commentators comprehensively teaches today’s youth as they prepare to undertake such complex tasks. Defining identity, coping with the burden of climate change, and learning to live in a still-fragmented world are the inheritance of future generations. In the meantime, the boy stands forever static in the Meštrović Studio Gallery of African Art- facing the exit, never able to move on from his burden.