The bell rang Monday morning at 8:15, signaling the beginning of the advisory period at New Trier High School, and that meant it was time to hear the weekend stories. I sat affixed in my chair as my classmates filed in, smiling and talking about the highlights.

"Charlie's party got busted, and I had to hop the fence in the back to get away."

"Tommy had to get his stomach pumped after Saturday."

"James finished eight Buschs in less than an hour. It was insane!"

Initially, these stories caught me by surprise, but after the first few weeks, they no longer shocked me, bothered me, or even made the tiniest footnote in my head. Drinking was the norm. It was inevitable and most high schoolers did it. Even though I chose not to drink, I felt the culture all around me, from the conversations to the social media posts. But I didn't think twice; I figured it happened at this large scale everywhere. That's where I was wrong.

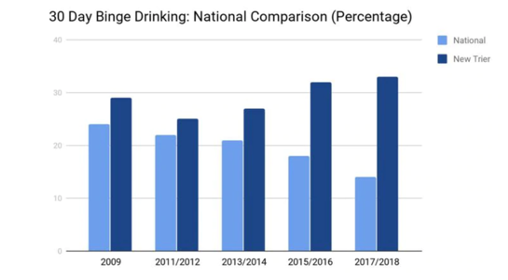

According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, an anonymous survey taken every year in physical education (see fig. 1), 33% of seniors at New Trier had engaged in binge drinking within the past month, meaning they had consumed around five drinks in a short period of time (Cullotta). This is more than double the national average of 14%, and the New Trier figure is probably conservative, as I know several people who lied on the survey out of fear that it wasn't completely anonymous. This year's data is not an isolated incident. Since 2012, the percentage of binge drinkers at New Trier has hovered around 30%, rising each year while the national average has actually fallen (Cullotta). This doesn't even account for underclassmen, and, in my experience, there were some heavy drinkers as early as sophomore year.

Wealthy suburbs typically have elevated teenage drinking rates, and New Trier is no exception. Located in the affluent city of Winnetka, Illinois and composed of several other well-off towns, the New Trier school district is amongst the wealthiest in the nation. According to a study done by Suniya Luthar and Chris Sexton, attending a wealthy school district directly correlates to characteristics that lead to binge drinking. First off, the "achievement pressures" are very high. During the school week, students are under immense pressure from their parents, peers, and themselves to excel in their studies and extracurriculars in order to get into a good college. As a result, when the weekend comes around, they like to unwind and destress, often using alcohol. One subject interviewed for the study stated, "we work so hard during the week, because of college pressure, that by the weekends we're totally, like, let the games begin," and this sentiment is echoed at New Trier. Additionally, the study found that "baseline peer popularity was significantly linked with increases in boys' substance use between middle and late adolescence" (Luthar and Sexton). This unfortunately is also true at New Trier. Those deemed "popular" tended to drink heavily, and many felt that in order to improve their social standing, they needed to do the same. Finally, in affluent communities, parents are often not as present because of their demanding jobs. This often leads to less supervision for the kids and makes them less likely to be disciplined (Luthar and Sexton). These factors from the study align closely with my experience at New Trier and likely contribute to the reason the school's drinking rate is so far above the national average.

This issue should be of particular concern to the school's administration. The school has invested greatly in substance abuse counselors and other resources, yet it seems to be to little avail. New Trier is the main commonality among the families of the community, and therefore has a substantial amount of influence over the issue. They have the best platform to reach the community and, given the trends in recent years, must do even more to promote change. As a high school, the goal is not only to release educated students out into the world, but also to keep the students safe and well-informed about the decisions they make, and in regards to alcohol, improvement is necessary in this area.

Currently, New Trier is looking to combat the problem through educating the students on the pitfalls of underage drinking. Sophomore year, each student must complete a semester of health education, which includes a unit on alcohol and substance abuse. This class is a requirement to graduate but, while it is well-intentioned, it has several fundamental flaws. First, the timing of the class is not ideal. Alcohol usage rises each grade level, and, frankly, not many sophomores actually drink on a consistent basis or at all. By the time the pressure to drink peaks during senior year, this course and what it taught isn't even an afterthought for students given that the information is now two years removed from their brains. In addition to this, the means in which the course is completed does not promote the importance of the information in an effective way. One key part of the alcohol unit is EVERFI's AlcoholEdu online programming, meant to be an interactive way for students to learn the dangers of alcohol and underage drinking. The online course includes a series of slides, videos, statistics, and more, with each section ending with a simple quiz. However, because this activity was completed individually, students more often than not rushed through the sections to finish as fast as possible, either to leave early or work on other assignments they deemed more important. As a result, the message was trivialized, and learning about the dangers of alcohol seemed more like busywork than an essential teaching.

The most fundamental flaw in the program, however, isn't really its fault. Alcohol education by nature must be taught with regard to risks, from short-term mental impairment to the risk of disease later in life. Without talking about these risks, there wouldn't be anything to talk about in alcohol education. But, as detailed in David Dobbs's groundbreaking article for National Geographic, "Teenage Brains," the brains of these students make decisions regarding risk in quite different ways than we might expect. Between the ages of 12 and 25, the brain undergoes an incredibly vast amount of change, remodeling and rewiring its very framework. Hence, the teenage brain is a "rough draft," and this is particularly apparent in risky situations. Contrary to common perception, teenagers actually go through similar cognitive processes as adults in decision-making, and usually even overestimate risk. The fundamental difference however, is how they weigh the risk against reward. This scenario can be illustrated in a study by Laurence Steinberg, a developmental psychologist at Temple University. Using a driving video game, Steinberg put teens in a relatively "cool" situation, where they were alone, and then in a group with their peers. The simulation was then repeated with adults. In the solitary situation, teens took about as many risks as adults, if not less. However, when the peers entered the room, the results changed significantly. While adults played the game exactly the same, the teenagers took twice the number of risks. According to Steinberg, "They didn't take more chances because they suddenly downgraded the risk. They did so because they gave more weight to the payoff."

The same can be applied to drinking situations. The majority of binge drinking cases occur in a group setting, like the second instance of the game. As a result, the payoffs of a laugh, potential increase in popularity, or a rush of social excitement are destined to outweigh the risks taught in class. In that moment, these comparatively trivial things seem so much bigger than the risks involved, and the sensation seeking that defines adolescence takes over. As educated and rational as teenagers may be, in this situation of pressure, they usually cannot comprehend what the healthy choice truly is. While I'm certainly not saying the school's current program is completely useless (two-thirds of seniors don't drink on a regular basis), it is not the entire solution. The decision must be taken out of the students' hands to a degree, and one group has the most control over this: the parents.

A similar problem, as detailed by Karen Ann Cullotta of the Chicago Tribune, was occurring at Stevenson High School, another wealthy suburban high school located in nearby Lincolnshire. Peaking at 25% of seniors binge drinking per the Illinois Youth Survey in 2014, Stevenson seemed headed down the same path as New Trier. However, only five years later, in 2019, Stevenson stands at 15%, just one percent above the national average. How was Stevenson able to completely flip the script in such a brief time-frame, while New Trier's problem became worse? According to Stevenson's substance abuse prevention coordinator Cristina Cortesi, the solution did in fact lie with the parents. Cortesi says, "We know all of the studies find the number one reason kids don't use is their parents," showing the influence that parents have (Cullotta). Given the high rate of drinking, it becomes clear that parents are generally misinformed about the law and the dangers of underage drinking. Stevenson used this information, starting a campaign largely targeting parents in the district. Due to the overwhelming success of this program, a similar program should be put in place at New Trier. In order to combat the rising prevalence of underage drinking at New Trier High School, the administration should target action towards parents by hosting seminars that inform about the misconceptions of drinking, underline the future dangers of alcohol abuse for children, and raise awareness about Illinois's social hosting laws.

One of the major goals of the seminars would be to dispel common excuses parents make for letting their children drink. In a qualitative study done by the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE), parents answered questions and gave honest reasons why they allow their children to drink. As it turned out, most answers were purely excuses, rather than legitimate reasons, to allow underage alcohol consumption. First off, many parents believed that allowing drinking would help "demystify" alcohol, teach safer practices, and make it less appealing to their children. Many referenced European customs, where children begin drinking in moderation around age 12, stating they believed that these children were less likely to have drinking problems later on. This is a complete myth. The study contradicts this belief, finding that "young people in many European countries are more likely to report drinking and drinking heavily than do youths in the United States" (Friese et al. 388). The same data holds true in the United States, where the younger someone begins binge drinking, the higher the chance of alcoholism later in life. Additionally, over half of the parents surveyed saw underage drinking as simply inevitable. They used this as an excuse for not being too strict about drinking in their household. However, this is obviously not the case. Even at New Trier, where students drink at a rate over double the national average, 33% binge drink, meaning 67% don't drink heavily or at all (Cullotta). This is a large majority, and using the national average, 86% of high school seniors do not engage in this behavior. In showing the parents that these misconceptions simply are not factual, it forces them to face the responsibility. The fact of the matter is that starting drinking early is never a good idea and that most kids rarely, if ever, drink. Showing this data also illustrates a fault in logic, and parents will hopefully see that just because some people are engaging in bad behavior doesn't mean they should allow their child to do so as well. Parents must now see themselves as accountable, causing them to be more strict regarding the rules they put in place.

Additionally, the program will inform parents of less obvious problems associated with underage alcohol usage in order to raise the stakes. When people think of problems related to alcohol, they almost immediately go to drunk driving, and rightfully so. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), in 2016, 28% of all driving accidents involved alcohol, and this number is likely even higher for teenagers. Impaired driving is hugely problematic and highly publicized, and most people have likely been directly or indirectly affected by it at some point in their lives. In the New Trier community, the number of alcohol-related driving accidents among teens has fallen, largely thanks to the widespread availability of services such as Uber and Lyft. As stated by New Trier superintendent Paul Sally, "'There's a little bit of a difference for a community like ours, with access to Uber and Lyft … it's wonderful that drunk driving has decreased because of it'" (qtd. in Cullotta). While this is obviously a major positive, the decrease in impaired driving may also give parents the perception that it is now safer to drink since their child won't be tempted to get behind the wheel. A majority of my friends actually had Uber accounts linked to their parents' credit card, as the parents wanted to ensure they used it when needed.

Although the most visible, drunk driving is far from the only risk that alcohol consumption may lead to. In their study, "The Short and Long-term Consequences of Adolescent Alcohol Use," Joseph Boden of Case Western Reserve University and David Fergusson of the University of Otago analyzed several direct problems stemming from alcohol that most wouldn't have initially considered. While their research agrees with Paul Sally's claim about the positive reduction of drunk driving, several other serious effects of binge drinking remain prevalent. For example, teenage pregnancy was 1.45 times more likely to occur with alcohol involved, and, due to the impulsivity caused by intoxication, teenagers were also significantly more likely to have unprotected intercourse and contract STIs. Additionally, at least 30% of all sexual violence occurs under the influence, and "female adolescents who binge drink may underestimate both their general risk of sexual assault, while overestimating the extent to which they may be able to fend off a sexual assault while intoxicated" (Boden and Fergusson). Early binge drinking also correlates to obesity later in life, which leads to many other health issues, and alcohol has proven to be a gateway drug for future use of tobacco, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. Furthermore, excessive alcohol use causes the body to release acetaldehyde, a chemical that can damage DNA and lead to increased risk of cancers such as breast, colon, throat, and liver, a connection a majority of people would never make ("Alcohol and Cancer"). By providing parents with these facts in the seminars, it should increase the urgency of the issue. Most parents associate the negative effects of alcohol use with comparatively minor side effects such as hangovers, but problems like sexual assault and teenage pregnancies are not the "learning experiences" parents have in mind when allowing consumption. In conjunction with the risk-reward behavior seen in teens as discussed earlier, it becomes clear that all of these issues are much more possible than most would think. By opening their eyes to such issues, parents will be more inclined to remember the scary truth that these potentially life-changing decisions are much more likely to be made with each and every drink.

Finally, it is imperative that the program makes parents aware of Illinois's social hosting laws. State law says that "For a parent or guardian, it is a violation of the law to knowingly permit, authorize, or enable, the consumption of alcohol by underage invitees" ("State Law in Illinois"). Punishment for doing so results in a misdemeanor charge with a fine of over $500, and if an underage drinker suffers serious injuries or dies, it is a Class 4 felony. These are both very serious offenses that should not be taken lightly. However, given the large number of parties that continue to be hosted, it becomes clear that many parents are unaware of these laws. While I knew there were laws that revolved around stopping this behavior, I had no idea the severeness of hosting underage drinkers, and I'm sure this is the same with most parents in the district.

In a study done for The Journal of Primary Prevention, researchers looked at the effectiveness of social host ordinances (SHOs) in 12 municipalities in California, and the results were striking. According to the study, in municipalities where campaigns were held to raise awareness for SHOs, 20% more parents said they knew about the laws than in those without campaigns (Paschall et al.). Additionally, these parents were twice as likely to believe that these laws would be enforced. If the potential risks underage drinkers face as discussed earlier were not enough to dissuade parents, this would hopefully push them over the edge in choosing not to host. Even if they view drinking as harmless experimentation, if they knew that a felony charge could be in play, it might make them think twice. New Trier could even up the stakes by regularly alerting law enforcement during special weekends, like long weekends or school dances. Awareness of SHOs also gives parents an out when talking to their kids about hosting. While teenagers often successfully convince their parents to host parties by promising that they'll be safe, clean up, or won't invite many people, they cannot deny the seriousness of criminal charges. Despite desires to fit in or destress, most teens are not willing to knowingly put their family in jeopardy. Parents can play off of this, especially those who fear straining their relationship with their child over drinking rules, since the child in most cases won't fault this logic.

Although the seminars would obviously have positive intentions, it can be argued that parents couldn't be forced to attend, and therefore they may not reach the desired audience. This is totally valid, as it is true that the school cannot force attendance. However, I have reason to believe that the events would still be largely attended. For example, an organization called Family Action Network (FAN) regularly hosts events with speakers giving advice about parenting at New Trier, and the auditorium is often full at these events. If the school were to promote the event heavily through email and social media, it is likely that the seminars would get similar attendance, if not greater. Given the amount of resources available, the school could potentially give more incentive to attend, such as a raffle at the end for prizes. Additionally, the seminars would cost next to nothing to put on. New Trier has abundant resources they are already putting towards alcohol education, and a few presentations would not cut into this budget at all. There is essentially no monetary risk, and potentially large rewards are possible, as demonstrated by the success at Stevenson High School. Furthermore, this is a process. Stevenson's change didn't happen overnight, and neither will New Trier's. Parents throughout the district, even those without children in high school, would be invited, and the earlier the misconceptions and dangers of underage drinking are taught, the more likely safer practices would be executed when it comes time to make decisions about setting rules for drinking.

In January of 2016, four former New Trier students died in a canoe accident in Wisconsin. Having consumed alcohol beforehand, the inebriated boys decided to go out on the icy Mill Lake, where they would eventually meet their deaths (Eldeib, McCoppin, and Berger). The death of the boys, all well-known and well-liked during their time at the school, shook the community greatly, and the tragedy was felt by almost everyone. However, the sad truth was that most people were not surprised that alcohol was involved, given its overbearing influence on New Trier's culture. Since this incident, the alcohol education hasn't changed at all, and that's a huge problem. If the school wants to fulfill its duty to its students and utilize its platform to create positive change, it must take action to prevent future tragedies that currently feel inevitable. While seminars for parents may not completely solve the issue, it at least opens up the conversation and gets parents to reconsider their stance, which can go a long way in eventually diluting the drinking culture and saving teens from dangers now and in the future.

Works Cited

"Alcohol and Cancer." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, www.cdc.gov/cancer/alcohol/index.htm. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Boden, Joseph M., and David M. Fergusson. "The Short- and Long-Term Consequences of Adolescent Alcohol Use." Young People and Alcohol: Impact, Policy, Prevention, Treatment, edited by John B. Saunders and Joseph M. Rey, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 32-46.

Cullotta, Karen Ann. "New Trier has seen an 'exponential' increase in students binge drinking. Officials say they need parents' help." Chicago Tribune, 8 Mar. 2019, www.chicagotribune.com/suburbs/winnetka/ct-wtk-teen-binge-drinking-tl-0314-story.html. Accessed 6 Nov. 2019.

Dobbs, David. "Teenage Brains." National Geographic, Oct. 2011, www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2011/10/beautiful-brains/#close. Accessed 6 Nov. 2019.

Eldeib, Duaa, Robert McCoppin, and Susan Berger. "4 Former New Trier Students Presumed Dead in Wisconsin Canoe Accident." Chicago Tribune, 4 Jan. 2016, www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-wisconsin-canoe-accident-20160104-story.html. Accessed 14 Nov. 2019.

Friese, Bettina, Joel W. Grube, Roland S. Moore, and Vanessa K. Jennings. "Parents' Rules about Underage Drinking: A Qualitative Study of Why Parents Let Teens Drink." Journal of Drug Education vol. 42, no. 4, 2012, pp. 379-91.

Luthar, Suniya S., and Chris C. Sexton. "The High Price of Affluence." Advances in Child Development and Behavior vol. 32, 2004, pp. 125-62, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2407(04)80006-5.

Paschall, Mallie J., Bettina Friese, Kristen Law, and Anna Lebedeff. "Increasing Parents' Awareness of Social Host Laws: A Pilot Study of Coalition Efforts." The Journal of Primary Prevention vol. 39, no.1, 2018, pp. 71-77, doi:10.1007/s10935-017-0496-1.

"State Law in Illinois." Underage Drinking in the Home, The Partnership for Drug-Free Kids and the Treatment Research Institute, socialhost.drugfree.org/state/illinois/. Accessed 14 Nov. 2019.

NHTSA. "Alcohol-Impaired Driving." Traffic Safety Facts: 2016 Data, Oct. 2017, crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812450. Accessed 14 Nov. 2019.