Situation: In the Mexican patriarchal and machista society, women are being sexually abused and murdered because of their gender. Today, many women in Mexico are experiencing horrible situations. I, a Mexican woman, have been affected by the violence against women in Mexico. Many people outside of Mexico do not know about the heartbreak that women in my country are going through. I believe it is my responsibility to educate people about this important issue in order to create a meaningful change for women in Mexico. I am giving this speech to my Writing and Rhetoric classmates to educate them about this crucial problem in hope that I will convince them to take action against the violation of rights that many Mexican women face every day.

Good afternoon everyone! It is an honor for me to be here today, giving a speech to the world’s future leaders. You are the leaders that not even a pandemic was able to stop from continuing their education and preparing to become tomorrow’s changemakers. You are the leaders who care about others and are willing to help marginalized people to make their voices heard. You are the leaders that the world needs. You are the leaders that Mexican women like myself need.

Patriarchal and Machista Society

Today, Mexico faces a crisis. I believe this crisis has its roots in the machista and patriarchal society Mexico still embraces. It is important to understand the differences between these terms. Machismo refers to the exaggerated expression of masculinity, which often leads men to act in sexist and abusive ways against women (Prado 1). This attitude permeates society and normalizes the idea that men are superior to women. A patriarchal society is one in which “men have the power and control the social, political, and economic systems” (Prado 10). Patriarchy gives males privilege and subordinates women. Both machismo and patriarchy are rooted in a common institution: misogyny, which is the hatred of and prejudice toward women and girls.

In a society like Mexico, where machismo culture and patriarchal societal structures prevail, machismo can be seen as the cultural abuse men exercise toward women, and patriarchy is the systematic advantage men receive over women. Both machismo and patriarchy empower and privilege men at the expense of women. This socio-cultural context devalues, disempowers, and discriminates against women. These two ideas are highly salient in the education and socialization of young people in Mexico.

Both consciously and subconsciously, many Mexican families are educating girls and boys to continue preserving these sexist power dynamics and attitudes every day. In my personal experience, at the young age of six years old, my mother told me to put shorts under my uniform skirt in order to protect my body from boys. At the time, I thought it was normal: I was a girl, therefore, I needed to be cautious of my body. But is it really normal for a six-year-old to worry about her body being sexualized by another six-year-old? Is it okay to socialize girls to take responsibility for protecting their bodies from an early age, instead of teaching boys that girl’s bodies should always be respected? I don’t think so. This is just one example of these subtle but significant life lessons imparted to Mexican children like myself that reinforce the idea that women and girls must police themselves to stay safe in a machista, patriarchal society, while men and boys in this society receive impunity for their actions.

Many people in Mexico do not understand how crucial young people’s education and socialization are to the future of our society. Not only are girls socialized to modify their lives to gain societal respect and value, but our society accepts boys’ sexist and abusive actions toward girls. Allowing such behaviors in childhood to be seen as acceptable and normal leads to greater abuses as boys become young men. Due to the vast amount of these travesties, it would be impossible for me to be able to comment on all of the forms of abuse that women in a patriarchal and machista society endure. Thus, I will focus on one of the most extreme examples of how such violent acts against women manifest: femicide, which is staggeringly high in Mexico yet continues to occur in the context of the patriarchal, machista country that so many women call home, where such crimes are state-sanctioned.

Femicide and Feminicide

Before I delve further into the heartbreaking experiences that many women in Mexico face in their daily lives, I first want to define the terms femicide and feminicide, as some people may be unfamiliar with their definitions and distinctions. According to The World Health Organization, femicide is the “intentional murder of women because they are women” (Sandin). In other words, women are being killed solely on the basis of their gender.

This might sound outrageous in the twenty-first century, a time when we assume and expect that women’s rights are established and protected in our society, but sadly, many women in Mexico lose their lives to femicide each year. According to Alejandra Marquez, an Assistant Professor at Michigan State University, “this year, on average, 10 Mexican women are murdered every day.” When I read this statistic, I was shocked and angry. Ten women every day. Ten families and friends suffer the loss of these women they love.

Let’s stop and think about that for a moment. Every single day in my country, ten women are taken away from their families, robbed of their dreams, and denied the right to live another day—not because they have committed some crime or wrongdoing, but because they were born female. How is this permitted to go on? Why has the Mexican government not intervened? Who is responsible for protecting the lives of these women and their rights to live as women in Mexico?

This is where the term “feminicide” comes in. Feminicide is a political term that refers to the “state responsibility for these murders [femicides] whether through the commission of the actual killing, toleration of the perpetrators’ acts of violence, or omission of state responsibility to ensure the safety of its female citizens” (Guatamala Human Rights Commission). In other words, the government of Mexico is guilty of feminicide because it has failed to protect not only the rights but also the lives of at least ten Mexican women per day, who are lost to femicide. Femicide is a crime committed by an individual who kills a woman on the basis of her gender; feminicide is a crime committed by the state that allows these killings to happen.

Life cases

Let’s put this into perspective by thinking about how this might impact each of our lives. Every person here has a woman in their life they love and care about—your mom, your sister, your friend or girlfriend, or any other woman you hold dear. Think of that woman now. Think of what you love about her, her hopes and dreams, the qualities that make her unique and special, the many people that love her, the reasons she is important to you. Then imagine that one day, she is found dead. The cause is determined to be “penetrating puncture wounds of the neck and head trauma,” and with 45% of her body burned by three people (“Danna’s Murder”). Imagine how you would feel finding out this news, suffering this loss, living without her, and wanting answers and justice.

Then, imagine that you and your family and all of the other people who cared about this woman join together to demand justice for her death, only to be told by the State’s Attorney General that this woman you all love was murdered because “she had tattoos all over the place” (“Danna’s”), or because of the “social decomposition and the current liberties that girls have to go out until very late…” (Rodriguez-Dominguez). Isn’t it painful just to think about it? Not only was a woman murdered through an act of femicide, the indignant comments made by the State’s Attorney General—a man in a powerful position who is responsible for ensuring that justice is served—dismiss the importance of this woman’s life and normalize and justify the senseless violence committed against her.

Sadly, for the family and friends of Danna Reyes, a sixteen-year-old young woman, this was a reality. Not only did they have to go through the pain of losing Danna but also the horror of realizing that the person in charge of serving justice minimized the violence she suffered and justified her violent death because “she had tattoos all over the place” or some other reprehensible excuse.

What is sadder still is that the State’s Attorney General is not alone in his approach to femicide. Many people in Mexico often blame women for their own deaths. They say things like, “Maybe if she wouldn’t have been out alone so late, this would not have happened,” or “She was dressed too provocatively,” or “She had tattoos all over the place.” These people refuse to see women as victims of a patriarchal, machista country guilty of feminicide, instead insisting that they are victims of their own choices.

But was “Jessica,” who was murdered at fourteen years old when she left her house to do her HOMEWORK at an internet cafe, a victim of her own choices? She never came back from that internet cafe and was discovered by her family and friends the next day dead in a crop field (Almarez). Her body showed evidence that her aggressor sexually and physically abused her prior to her death (Almaraz).

What about Ms. Hilaria Caballero, an eighty-four-year-old woman, who went to work and went missing? Was she a victim of her own choices? Four days after her disappearance, she was found in a canyon, her body covered with rocks, wearing only her blouse. Her pants and underwear had been removed and marks around her neck showed that she had been strangled to death (Fernanda RuAL). Her family could not even bear to see her corpse because of how mangled and brutalized it was from the torture, trauma, and violence she was subjected to prior to her murder (Fernanda RuAL).

Or what about Sara A. Salinas, a twenty-two-year-old woman who loved to play piano, play sports, and was dedicated to her college career until one morning, her mom found her dead, in HER BED? She was in her house, in her bed sleeping when her aggressor entered her room and killed her. He tried to make her death look like a suicide, but the “autopsy revealed that the cause of death was asphyxiation due to suffocation, her thorax was depressed. External factors in the scene and on her body clearly indicate that she was murdered” (Sandoval). Was she a victim of her own actions? By sleeping in her bed at night, did she commit some mistake or misstep that led to her death? Or was she the victim of a murderer out to kill her as she peacefully rested?

These examples show that these crimes happen to women of any age, who are innocent of wrongdoing, just going about their daily lives. Were these women murdered because of their own actions? Should they have done more to protect themselves, as people with the patriarchal and machista mindset of Mexico might claim? Or should they have been respected, safe, and free to go about their daily lives without fear of death in their own home country?

The reality is that no woman in Mexico is a victim of her choices. Women in Mexico are victims of a patriarchal, machista society that fails to protect their basic human right to live every day. They are victims of the indifference that exists in Mexico, a country with high rates of femicide that takes no responsibility for these crimes, where women’s lives are taken from them, and no one seems to care. They are victims of an irresponsible government that commits feminicide by neglecting these crimes and failing to intervene to protect the lives of female citizens, where the President himself minimizes the high rates of femicide in the country by saying they have “been manipulated by the media” (Agren). Mexican women suffer grave abuses in a patriarchal, machista society that normalizes and perpetuates violence against women—some of them survive, many of them die, and all of them are oppressed by these misogynistic institutions.

Call to action

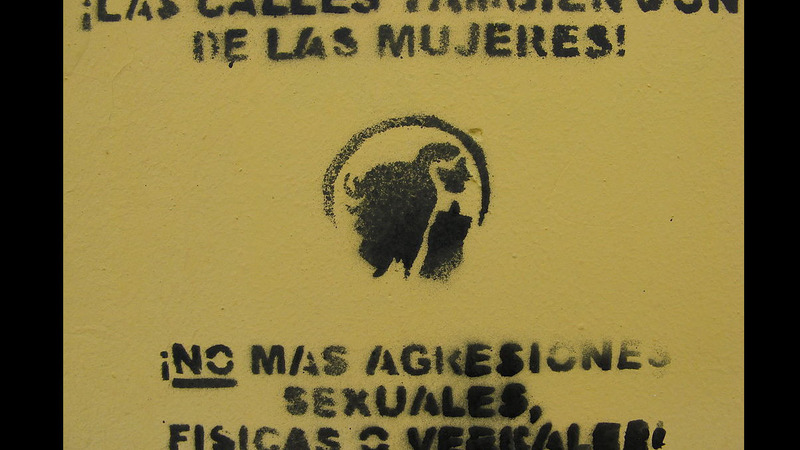

This must end. The state-sanctioned killing of women in Mexico must end. The impunity of the murderers and the government who allow this to continue must end. The sexist socialization and education practices that give way to violence against women must end. And if we are to end these injustices, we must re-examine and dismantle the systems and cultural norms that created and sustain them. We must dismantle the patriarchy. We must reject machismo. We must envision a future in which women are valued, empowered, respected, and celebrated.

I have hope that one day women in my country will be free to live their lives fully, freely, and safely. I believe that one day, families and friends in Mexico will no longer suffer the loss of women they love. I believe that one day women in Mexico will enjoy the same safety that I am provided right here on our campus when I return from the library at three in the morning, alone and without fear of being killed because I am a woman. I believe that one day, women in Mexico will go to their jobs, schools, and activities, acting as positive agents of change in Mexico without fear of losing their lives. I believe that one day, women in Mexico will be able to sleep at night without fearing they will not live another day because someone is out to murder them. I believe that one day femicide will no longer be a nightmare haunting so many Mexican women’s daily realities.

Let me conclude by saying that this change, this new life in Mexico where the patriarchal and machista society no longer exists, can only be possible if people like you, people who care about others, people who are working hard in order to become changemakers, become part of the solution to this issue. We must raise awareness and spread our knowledge about this nightmare many women in Mexico face. Let’s amplify the voices and stories of the many women suffering from this situation, so they can be heard by more people in power, by U.S leaders and organizations that can intervene to end this situation. Soon, we will have a new President and the first female Vice President, who are committed to gender equity, so now is the time to push for the people in power in the United States to work with international institutions and other countries to hold Mexican misogynist leaders accountable. After hearing this speech, I hope that each of you understands the nightmare of being a woman in the machista, patriarchal Mexican society, and becomes involved in helping Mexico to wake up from it.

Works Cited

Agren, David. “‘The message he’s sending is I don’t care’: Mexico’s President Criticized for Response to Killings of Women.” The Guardian, 21 Feb. 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/21/mexico-femicide-crisis-amlo-response.

Almaraz, Lui. “Jessica, de 14 Años, salió a un cibercafé... Fue encontrada sin vida en el Edomex.” CulturaColectiva News, 28 Aug. 2020, https://news.culturacolectiva.com/mexico/jessica-14-anos-salio-cibercafe-encontrada-muerta-estado-de-mexico/.

“Danna’s Murder Was Not Classified as Femicide, Despite Violence.” Newsy Today, 30 Aug. 2020, https://www.newsy-today.com/dannas-murder-was-not-classified-as-femicide-despite-violence/.

Fernanda RuAl. EN TU MEMORIA HILARIA (Tomado De Otro Muro). Facebook, 12 Nov. 2020, www.facebook.com/fernanda.rual.5/posts/845017752977001. Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

Guatemala Human Rights Commission. “Fact Sheet | Femicide and Feminicide.” GHRC-USA.org, “https://www.ghrc-usa.org/Programs/ForWomensRighttoLive/factsheet_femicide.pdf. Accessed 12 Nov 2020.

Marquez Guajardo, Alejandra. “Mexico’s Other Epidemic: 10 Women Murdered a Day.” United Press International, 29 May 2020, https://www.upi.com/Top_News/Voices/2020/05/29/Mexicos-other-epidemic-10-women-murdered-a-day/9011590757775/. Accessed 7 Nov 2020.

Prado, Luis Antonio. “Patriarchy and Machismo: Political, Economic, and Social Effects on Women.” 2005. California State University, San Bernardino, Master’s Thesis. Theses Digitization Project, https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2623. Accessed 7 Nov 2020.

Rodriguez, Yazmín, et al. “Mexico Registers Four Disturbing Femicides.” El Universal, 30 Aug. 2020, https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/english/mexico-registers-four-disturbing-femicides.

Rodriguez-Dominguez, Maria. “Femicide and victim blaming in Mexico.” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, 2 Oct. 2020, https://www.coha.org/femicide-and-victim-blaming-in-mexico/.

Sandin, Linnea. “Femicides in Mexico: Impunity and Protests.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 19 Oct. 2020, www.csis.org/analysis/femicides-mexico-impunity-and-protests. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020.

Sandoval, Noemi Salinas. “Mexico: The Femicide of Sara Abigail Cannot Go Unpunished, We Demand Justice!” In Defence of Marxism, 13 Mar. 2020, www.marxist.com/mexico-the-femicide-of-sara-abigail-cannot-go-unpunished-we-demand-justice.htm.

Discussion Questions

Good speakers and writers often focus on something very particular, concrete, and specific. Other times, they offer more general pronouncements or observations. Comment on Rebeca’s use of specific cases, in her section titled “Life Cases,” and how those specific, concrete examples help advance her overall argument.

Explain and evaluate how Rebeca catches her audience’s attention at the beginning of the speech (also known as her exordium) and how she calls her audience to action at the end of the speech (also known as her peroration). Given her intended audience and the particular timing of her argument, do you think her strategies are effective? What else might she have done to tie her argument to not only her intended audience but also the particular historical or cultural moment they share with her?