The issue of poverty in America was pushed to the forefront of American politics in the early 1960s when the Kennedy administration rediscovered "the other America." This group consisted of the estimated one-quarter of Americans who lived in poverty. Lacking basic necessities, food, and housing, this ostracized group had been separated from mainstream American culture, and more importantly, public consciousness (Oyemade 592). In response to these startling realizations, the government took steps to reduce poverty rates in the United States. Among the programs implemented was Project Head Start, which was founded on the belief that benefits from universal early childhood education for disadvantaged children early in life could pay dividends in the future (Oyemade 591). Conceived as a "social action" experiment, the long term goal of Head Start was to interrupt the poverty cycle called intergenerational poverty in academic realms by providing better educational resources to underprivileged children in highly impoverished areas. Since its inception, government funding of Head Start has increased sixfold when adjusted for inflation. Today, the government spends about 8.5 billion dollars per year on Head Start, equating to just under $10,000 per student enrolled ("Head Start Program Facts"). With poverty and near-poverty rates remaining relatively constant since the program's inception, the question has been raised as to the efficacy of Project Head Start. Through the presentation of credible studies, the ineffectiveness of Head Start becomes clear. As it is currently run, Head Start is not an effective means of lifting children out of poverty or reducing intergenerational poverty. To take advantage of current infrastructure, government funds should be concentrated in the poorest areas and more monetary support should be pumped into proven, successful programs that will make Uncle Sam's dollars go a lot further.

In this paper, I will first present poverty and crime-related facts showing the alarming poverty trend in the United States. A history of Head Start will then be laid out, with exploration into the perceived sociological and economic truths Head Start was established on, its original goals, and Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty as a whole. I will then discuss the argument for Head Start's positive impact on children before rebutting such claims and presenting evidence against the efficacy of Head Start. I will then suggest the reallocation and injection of funding into more effective programs for lifting children from poverty.

POVERTY/HEAD START FUNDING FACTS

When President Johnson announced the "War on Poverty" in 1964, the poverty rate was 19 percent. In the 50 years since then, government spending on low-income programs has increased nearly elevenfold (twenty-five fold if Social Security and Medicare are not included) ("Federal Budget"). In those same 50 years, inflation-adjusted per capita GDP (a strong indicator of standard of living) has risen about 167 percent (from about twenty to fifty thousand dollars) ("GDP Per Capita"). Despite ample spending and a rising average standard of living, the 2014 official poverty rate was 15 percent, a meager 4 percent drop from 1964 ("Historical Poverty Tables"). With these startling statistics in mind, the way the US allocates its budget toward poverty reduction needs to be rethought. This begins with the early childhood education program, Head Start.

HISTORY

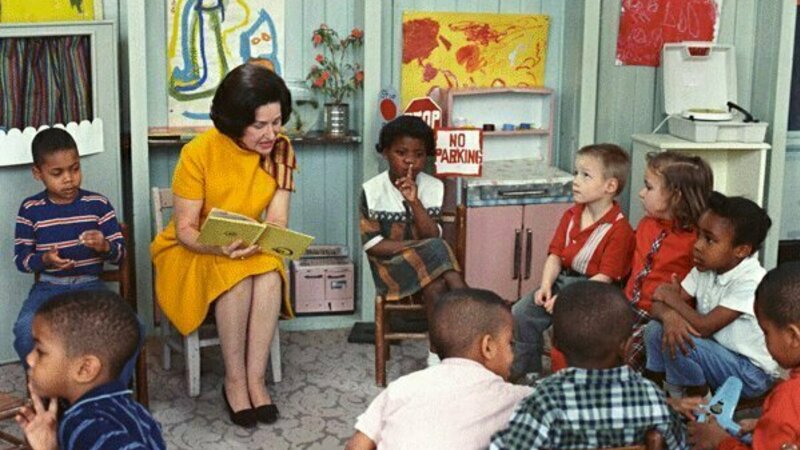

Head Start was instituted in 1964 as a result of President Lyndon Johnson's "War on Poverty" with the goal of stopping the cycle of poverty where the struggles of poverty cause poor parenting, welfare dependency, and "produce children with social and intellectual deficits....,leading again to inappropriate parenting." The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 established the Office of Economic Opportunity, which was created, according to President Johnson, "not only to relieve the symptoms of poverty but to cure it; and, above all, to prevent it." To achieve this, the Head Start program aimed to improve the learning skills, social skills, and overall health of poor children in order to catch them up to their more advantaged peers. It was conceived on a few then-accepted principles: (1) that welfare dependencies are transmitted through generations and (2) that the "flawed character" (inherent disorganized behavior) of poor children is what caused them to perform worse in school (Oyemade 591).

Head Start has enjoyed consistent public backing since its inception. It has not been difficult to convince the public that early-childhood education can lift children out of poverty (Oyemade 591). Subsequent support led funding to be increased substantially during the Clinton and Bush administrations (Currie and Thomas 341). Today, federal funding exceeds 8.5 billion dollars, which equates to just under $10000 per child for 927,275 enrollees. ("Head Start Program Facts").

SUPPORT FOR HEAD START

Political support for Head Start has been has been influenced by widespread public support behind the seemingly intuitive notion that child care programs can improve human potential later in life. Another argument supporting Head Start upon its inception was the notion that programs that help the children of the poor are "public investments in human development" (Oyemade 591). This development has been shown in some studies that show evidence pointing to the efficacy of Head Start. A study by Ju Eunsu was conducted using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) from 1970 to 2005. She found that Head Start participants who remained in the program for over one year were more likely than all other cohorts (short-term participants, no-preschool, and preschool) to achieve higher levels of educational attainment. No direct relationship was found between enrollment duration and economic status, although higher educational attainment was found to result in higher economic status. In all cohorts, effect on welfare dependency was not clear (Ju 158). In another study, Head Start was found to have "positive and persistent effects on schooling attainment of white children"(Currie and Thomas, 341). The study did show academic improvement for African-American students as well, but the positive effects were smaller and wore off into adolescence. In both studies, higher usage and easier access to preventative medical care among Head Start enrollees resulted in higher rates of immunization better overall good health (Currie and Thomas 342; Ju 42).

REBUTTAL OF SUPPORTING STUDIES AND ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE OF INEFFECTIVENESS

Perhaps there is an excess of evidence supporting the ineffectiveness of Head Start in this paper, but it is merely a result of the plethora of published evidence concerning the ineffectiveness of Head Start Programs. These studies find negative evidence concerning the actual life outcomes of participants as well as the quality of Head Start classroom environments.

First off, the principles on which Head Start was founded have come under strong opposition in the last twenty years. As our knowledge of poverty transmission has evolved, new ideas are being accepted and old ones discredited. For example, the notion that welfare dependency is transmitted through generations has been discredited by numerous studies. In fact, Eunsu Ju's study supporting the efficacy of longterm Head Start participation confirmed this fact when it found no relationship between welfare dependency and Head Start participation, even when controlling for numerous background variables. Oymade found "little evidence" to support that the transmission of welfare dependency is based on inadequate values instilled in children by welfare-dependent parents. Early childhood education has not been found to affect welfare dependency, which was an original premise on which Head Start was founded. The second principle on which Head Start was based, the "flawed character" view, has also been criticized abundantly. Poor children do not have inherently disorganized behavior in fact, Oyemade found that "the poor have similar beliefs to other Americans" in terms of what it takes to be successful, but "lack the means and resources to actualize those beliefs." In light of this, it seems Head Start's original goals of value installation and a reduction of welfare dependency through such installation are outdated and discredited.

Another supporting study mentions "improving social skills" as an original aim of the Head Start program in its introduction, but the study makes no attempt to quantitatively study children's social outcomes (i.e. instances of behavioral issues, criminal activity later in life). This supporting study did show that children participating in Head Start programs showed improvement on test scores and schooling attainment, but only for whites. Blacks do initially make improvements from Head Start participation, but these gains are "quickly lost." In the end, there is no significant difference in test scores or probability of grade repetition among the black students in the long run (Currie and Thomas 360). If Head Start only improves the outcomes of white children, is it really doing its job? If the goal of the program was to give a boost to poor students of all races, this study showed that Head Start failed.

Many studies have reiterated the "fading out" of the initial positive effects of Head Start. One study through the University of Michigan gives insight into why the effects of Head Start are being reversed. Using information from the National Educational Longitudinal Study, Valerie Lee and Susanna Loeb found that Head Start locations are concentrated in the most poverty stricken areas; the most disadvantaged children from these areas also attend the lowest quality schools. Their study finds that "Head Start alumni attend systematically inferior schools thereafter" and "any boost is undermined by subsequent education in lower quality schools" (Lee 74). The result of geographically concentrated poverty (as is common in the US) poses a significant threat to the effectiveness of Head Start programs in those areas. If the benefits of pouring significant funds into Head Start programs in the most impoverished areas are only being reversed, the government is essentially throwing money away.

This geographically concentrated poverty also imposes significant negative effects on the quality of Head Start programs in those areas. As stated previously, Head Start locations are concentrated in the most poverty-stricken areas. Neighborhood poverty in these areas is directly correlated to lower academic performance, increased behavioral/emotional problems, and lower earnings later in life. One would think that Head Start locations should be a safe haven, a bright spot in the lives of underprivileged children, but a recent collaborative study from New York University shows otherwise. Using data from the Head Start Impact Study (a national randomized controlled trial conducted from 2002-2003), researchers found that "educational settings convey the influence of neighborhood poverty on developmental outcomes" (McCoy 150). Another study showed that "the level of economic disadvantage in the neighborhoods surrounding Head Start classrooms is associated with the quality of those classrooms" (Phillips 488). This has stunning implications: these findings mean that the lowest quality Head Start locations are in the very poorest areas. In other words, the poorest children attend the lowest quality Head Start locations.

Why are these locations of the lowest quality? Head Start programs who serve the poorest children (and exist in the poorest neighborhoods) have fewer fiscal resources because they exist in areas with smaller tax bases. The study also found that the more hours spent in low-quality programs, the worse children's' behavioral and academic outcomes. According to the study, these outcomes were caused by lower quality teachers and fewer fiscal resources. Negative student-teacher interaction was found to have the biggest influence on the future behavior problems, and lower material quality in Head Start classrooms (caused by fewer fiscal resources) was found to cause poor approaches to learning.

Why do student-teacher outcomes tend to be worse in lower quality schools? Lower quality schools exist in more economically disadvantaged areas, and this disadvantage has an adverse effect on teacher quality. It is more difficult to attract the most qualified teachers to the most disadvantaged areas because the pay disparity is so massive. For example, a Head Start teacher in the Bronx makes an average of $17,000 per year, whereas a teacher in Manhattan several miles away makes an average of $38,000 per year (Phillips 487). Teachers in disadvantaged areas are also subject to greater stress by living in a higher-crime and lower-resourced setting, impairing their ability to educate sufficiently. This impairment caused "harsh and critical interactions with children" and "unsupportive or punitive environments" in many cases (McCoy 157). The data from these studies supports the notion that Head Start locations are simply a conduit for imposing outside economic disadvantages on children inside the classroom. Essentially, the children who have the greatest need for Head Start are attending the lowest quality facilities with the lowest quality teachers. For a program that was established to level the playing field between disadvantaged children and their peers, these studies reaffirm its shortcomings.

The effect of these poverty-stricken areas on the physical health of Head Start teachers has been quantified as well. In a study by Temple University of Head Start locations throughout Pennsylvania, Head Start teachers were found to have higher rates of diagnosed depression and poor health status than a national controlled sample of people of similar age, education, race, and marital status (Whitaker 3). One can infer that teachers in poor health may not be teaching to the best of their ability. They may not be providing the highest quality education they can provide to students. Head Start cannot educate students sufficiently if teachers are of poor health.

In addition to its wide quality disparity in different locales, Head Start does not serve the children who need its services most. According to the Head Start Act, a family's income has to lie below the poverty line for their children to be eligible for Head Start services. There are various exceptions and statutes to this rule, which, according to the Head Start Bureau, results in 6 percent of Head Start participants not being poor. However, a study by Indiana University concluded that percentage of non-poor children in Head Start programs at enrollment were much higher than reported (28 percent). Moreover, the percentage increased substantially throughout the school year, from 28 percent to at least 34 percent, and possibly as high as 50 percent (Besharov 613). Head Start administrators frequently "bent the rules" to meet federal enrollment targets and made exceptions for families they deemed were in particular need. In addition, the income line used by Head Start is not adjusted geographically for differences in cost of living (Besharov 625). This causes even more disparity; for example, a "non-poor" child in New York who is denied enrollment may be much worse off than a "poor" child in Omaha who is granted enrollment. These many factors contribute to the large number of non-poor children enrolled in Head Start programs at the end of a given school year. A majority of the non-poor children spots in Head Start could presumably be filled with poor students who are more deserving of the service. Head Start is not serving the children who need its services the most.

Another possible implication of the deceivingly high number of non-poor children in Head Start is the overstatement of the program's impact as measured by various studies. If Head Start students measured in previous studies were assumed to be poor (by the government's standards), and a good percentage of them (somewhere between 25 and 50 percent) were not, the positive data showing progress in these studies could be skewed. Children may have benefitted more from being of higher socioeconomic status than from the influence of a Head Start education.

As poverty rates in the United States continue to stagnate, we need to rethink our approach to childhood education or even more government funding will be washed away.

USING THE DATA TO OUR ADVANTAGE: PROJECT FOLLOW THROUGH

While the goals and premise of the Head Start program are valiant and worthwhile, it has ultimately been proven unsuccessful as a whole. However, early childhood education could prove to be a beneficial means of reducing poverty the results from this claim are clear in the studies that show initial gains from Head Start participation but the eventual disappearance of those gains. If the data available are used appropriately, Head Start could have a more positive impact on the lives of disadvantaged children. It has been suggested by scholars that sustained educational programs (ones that aid children as they enter grade school and beyond) could sustain and reinforce the initial gains made by Head Start participants (Lee 75). In fact, there is evidence showing these programs can have immense success.

Conceived in 1969, Project Follow Through aimed to provide "enhanced instruction in early childhood education," by providing direct supplementary instruction to students from Kindergarten to third grade in 180 elementary schools in highly impoverished areas. Many of those students had been Head Start participants as well. In a study by conducted by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, involvement in Project Follow Through from Kindergarten through third grade found that "students perform significantly better than their controls" on all five measures of academic success they had lower high school dropout rates, lower retention rates, higher graduation rates, higher college application rates, and higher college acceptance rates (Meyer 390). Government funding for Project Follow Through was eventually phased out, but strong evidence exists in support of the efficacy of "following through" on initial Head Start gains.

Given what we know from the other studies discussed in this paper, these findings make sense. Though a large physical infrastructure exists in terms of Head Start facilities, I propose that the government should reallocate some of the funds from the least impoverished Head Start locales to form elementary school "sustained gains" programs in the areas that need it most. More of the federal budget should be allocated to creating a government-sponsored system of supplementary elementary school programs in the poorest areas. More government funds should also be pumped into the pre-existing Head Start systems in those areas to ensure the high structural and instructional quality. Even though I am advocating for more money to be spent, the data suggest these dollars will prove effective in sustaining the gains from Head Start. In addition, teachers should receive frequent health screenings to ensure they teach to the best of their ability. The reallocation and addition of more funds based on the data presented will help Head Start achieve its main goal: giving disadvantaged children a boost to lift themselves out of poverty.

In conclusion, it is clear that Project Head Start, as it is currently run, is not an effective means of lifting children out of poverty or reducing intergenerational poverty. The assertion that preschool intervention would lead to the eventual elimination of poverty from the ground up has been seen as an "oversimplified solution to a very complex problem" (Oyemade 591). The validity of this claim can be seen in the volume of studies examined in this paper. Many factors influence the quality of early childhood education including location, economic and physical condition of surroundings, quality of subsequent schooling, administrator behavior, and health and salary of teachers. Moreover, government funds will continue to be spent inefficiently if Head Start continues to run in its current state. In order to effectively reduce intergenerational poverty through improving the life outcomes of poor youth, funds need to be siphoned to improve the quality of Head Start locations in the poorest areas and establish supplementary instruction centers to sustain the positive effects of Head Start when students enter subsequent schooling. If the Head Start system is improved using the data available, the country will be well on its way to reducing poverty and providing a greater level of educational equality for years to come.

Works Cited

Besharov, Douglas. "Nonpoor Children in Head Start : Explanations and Implications." J ournal of Policy Analysis and Management (19861998) 26.3 (2007): 61331. Print.

Currie, Janet, and Duncan Thomas. "Does Head Start Make a Difference?". The American Economic Review 85.3 (1995): 341–364. Print.

"The Federal Budget in 2013" Congressional Budget Office. (2013) 2015. Web. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/45278

"GDP Per Capita (Current US $)." The World Bank. The World Bank Group. 2-15. Web. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD

"Head Start Program Facts Fiscal Year 2014." United States Department of Health and Human Services ( 2015): 110. 2015. Web.

"Historical Poverty Tables Poverty by Definition of Income (R&D) Table 5." United States Census Bureau (2014). 2015. Web. https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/histo...

Ju, Eunsu. "Long-Term Effects of Head Start Enrollment on Adulthood Educational Attainment and Economic Status: A Propensity Score Matching Approach." Dissertation Abstracts International 7 0.9A (2010). Print.

McCoy, Dana. "Neighborhood Economic Disadvantage and Children's Cognitive and Social-Emotional Development : Exploring Head Start Classroom Quality as a Mediating Mechanism." Early Childhood Research Quarterly 32 (2015): 150.9. Print.

Meyer, Linda A.. "Longterm Academic Effects of the Direct Instruction Project Follow Through." The Elementary School Journal 84.4 (1984): 380-394. Web.

Phillips, Deborah. "Child Care for Children in Poverty : Opportunity Or Inequity?" Child Development 6 5.2 (1994): 472-92. Print.

Oyemade, Ura Jean. "The Rationale For Head Start As A Vehicle For The Upward Mobility Of Minority Families: A Minority Perspective." American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 55.4 (1985): 591-602. PsycARTICLES. Web. 16 Nov 2015.

Whitaker, Robert. "The Physical and Mental Health of Head Start Staff : The Pennsylvania Head Start Staff Wellness Survey, 2012." Preventing Chronic Disease 10 (2013). Print.

Discussion Questions

- Daniel's paper critiques the effectiveness of a popular social policy meant to help young children succeed in life. It would be easy to characterize the author of such an argument as callous or cynical. How does Daniel manage his own ethos throughout the paper so as to sidestep such an accusation?

- Daniel uses several strategies to incorporate counterarguments into his paper. Identify one or more of the strategies and explain how they work to boost the effectiveness of his argument. Why do you think Daniel asked the following in the form of a rhetorical question: "If Head Start only improves the outcome of white children, is it really doing its job?"

- The second paragraph of Daniel's paper provides a "road map" for the whole argument. Identify keywords in this paragraph that you see repeated throughout the rest of the paper. How does this paragraph give structure to the argument as a whole? How might you employ a similar strategy in an assignment for your course?