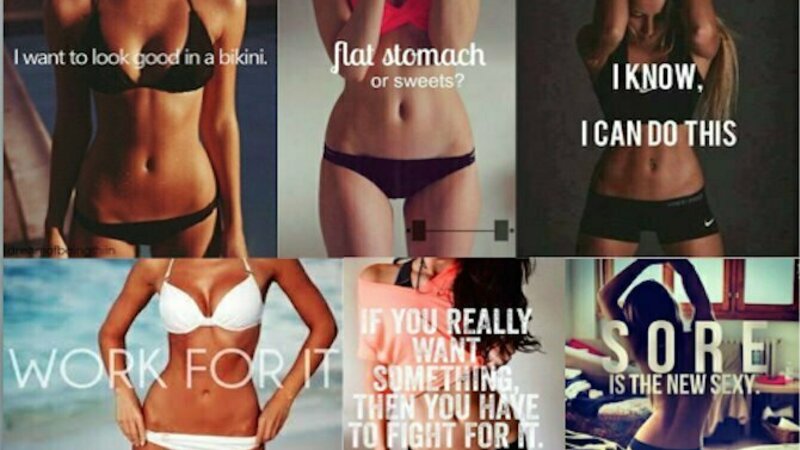

"Every society has a way of torturing its women, whether by binding their feet or by sticking them into whalebone corsets. What contemporary American culture has come up with is designer jeans," states Joel Yager, an M.D. psychiatrist who studies eating disorders. Eating disorders are becoming more prevalent and are occurring at younger ages in our modern society. Some would argue this is a direct result of the overpowering influence of the media, which aggressively advertises a thin yet toned female body. This manifests itself in a very concentrated form as "thinspo" or "thinspiration"—the inspiration to be thin—on social media sites (Angyal). Thinspo typically entails a strict mantra pasted over a highly edited photo of a woman's barely-clothed, malnourished body. Research has been conducted supporting a correlation of viewing images of thin models, or thinspo, and decreased body satisfaction, lowered self-esteem, and negative emotions, all of which contribute to the development of eating disorders (Polivy and Herman 2). However, the effects of viewing images of fit women, also called "fitspo" or "fitspiration," on eating disorders have not been thoroughly studied. Thus, this paper serves to study fitspo viewed by young women on social media sites as a potential therapy to eating disorders.

Before fitspo is evaluated as a potential therapeutic method, the prominent issues—the rising of women's skewed body image and body dissatisfaction, the growing influence of social media, and the increasing prevalence of eating disorders—must be investigated. The correlation of viewing media, specifically in the form of thinspo, and body dissatisfaction must be established with regard to the development of eating disorders. Using thinspo as a model for comparison, I will evaluate current public concern about fitspo and explore fitspo's potential to work against influences, such as thinspo, as a therapy for eating disorders. Fitspo's potential influence will be determined with dependence on two factors, namely the individual person and the type of fitspo.

To fully understand how fitspo influences people, the social and cultural context must first be defined and analyzed. In today's society, body dissatisfaction, social media influence, and eating disorders are rapidly growing, interconnected issues. Body dissatisfaction is the perception of one's body image in which one's ideal body size or shape differs from that of their current body. Many psychologists would concur that body dissatisfaction is connected to the culturally defined ideal of beauty (Sivert and Sinanovic 55). This ideal of beauty is largely constructed and promoted via the media. The media is our society's form of mass communication, and it often contains underlying social ideals. Media sources include magazines, television, radio, music, Internet, and more. Although these sources were created to be beneficial, their hidden messages, particularly those containing ideals of physical appearance, can have negative psychological effects and lead to serious illnesses such as eating disorders. Eating disorders—anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and binge eating—are defined as an extreme emotions, attitudes, or behaviors with food and/or one's weight (National Eating Disorders Association). The rates of eating disorders are increasing and beginning to occur at younger ages (Derenne and Beresin 4). However, before this rise in eating disorders is directly analyzed, we must first investigate the prominence of body dissatisfaction.

Studies have repeatedly shown that the vast majority of women, particularly those in Western cultures, are dissatisfied with their body shape and size (Grogan 26). This poses serious concerns since body dissatisfaction is a risk factor for eating disorders and has been linked to dieting, bulimic symptoms, depression, and low self-esteem (Homan et al. 50). To understand this body dissatisfaction better, numerous silhouette studies, in which women were presented with images of female silhouettes ranging in size from very thin to very large, were performed. The women were asked to identify which silhouette depicted their current body and which silhouette depicted their ideal body. Results showed a tendency for women to choose a thinner ideal body than their choice of their current body, supporting a dissatisfaction with their current figure (Grogan 26). Furthermore, a survey done by Psychology Today reported that 55 percent of women were dissatisfied with their weight and 45 percent of women were dissatisfied with their muscle tone (Grogan 29). Muscle tone has recently become more desirable among young women in Western cultures due to a shift in society's view of an ideal female physique.

The currently idolized female body, particularly in Western cultures, is not only very thin, but also very fit (Homan et al. 50). In fact, in interview studies conducted at Manchester Metropolitan University, many women reported a desire to be "skinny but shapely" (Grogan 38). This perfect balance of thin yet muscular is difficult to obtain and maintain, especially in comparison to simply being skinny. Essentially, this makes the ideal body more taxing to achieve and creates a greater disconnect between the average women's body and the idealized body often seen in the media.

The media is often blamed, out of convenience and ease, for producing unrealistic standards of physical beauty. However, historical research shows that the ideal female body has always been constructed by the political climate and cultural ideals. Moreover, this ideal female figure has typically been difficult and often unrealistic to achieve. What separates the modern, Western influences from the previously studied influences on the idolized female physique is a clearly more powerful presence of the media in today's society (Derenne and Beresin 4). In fact, women in interview studies claimed that their body satisfaction was influenced by thin models viewed in the media (Grogan 35). However, the best demonstration of the media's influence lies in a study comparing the rates of eating disorders in Fiji before and after the arrival of television in 1995. Previously in Fiji, a rotund body type was preferred because it signified wealth and the ability to care for one's family. Due to this cultural norm, only one case of an eating disorder had ever been reported in Fiji before the introduction of television. However, in 1998, after television arrived in Fiji, the rates of eating disorders skyrocketed from 0 to 69 percent. Furthermore, young Fijians repeatedly cited their weight-loss inspirations to be the attractive, thin actors on TV shows such as "Beverly Hills 90210" and "Melrose Place" (Derenne and Beresin 258). The stark difference in eating disorder rates prior to and following the arrival of television in Fiji demonstrate the strong influence media has on sociocultural ideals and people's behaviors. Furthermore, this study supports a correlation between media influence and eating disorders.

The media's influential role in creating an unrealistic standard of female physical appearance is often highly emphasized in explanations for the rising prevalence of eating disorders (Homan et al. 50). Not only are eating disorders growing in numbers, but they are also increasingly occurring at even younger ages (Derenne and Beresin 6). However, to more fully explain this rising prevalence of eating disorders, we must first analyze dieting.

At any given time, 40 percent of American and British women are dieting. Furthermore, 95 percent of women reported dieting for some period during their life (Grogan 42). When asked why they dieted, women reported the number one reason as looks or appearances. Women also repeatedly correlated thinness with feelings of higher confidence (Grogan 32, 44). However, these women reported very unhealthy dieting behaviors including fad dieting and extreme caloric restrictions (Grogan 42-44). These behaviors are indicative of a skewed relationship with food, a primary characteristic of eating disorders.

These unhealthy behaviors are becoming more prominent at even younger ages.

In fact, a 1994 survey reported that 40 percent of 9-year-olds have been on a diet (Derenne and Beresin 6). Dieting behaviors, especially extreme dieting behaviors, are often a gateway to eating disorders. Therefore, this spread of dieting to younger age groups demonstrates a worsening of the problem in regard to unhealthy relationships with food. Furthermore, this poses a serious concern: children could become permanently ingrained with the ideas that their self-worth is based solely on their body, and that dieting is a "normal" behavior to be used as method to achieve higher self-worth.

The correlation among the prevalent issues of body dissatisfaction, social media influence, and eating disorders is continuously being researched. However, there has recently been a formation of online communities that add new aspects to this ongoing research. These communities support and share "thinspo", defined as the inspiration to be thin, or "fitspo", defined as the inspiration to be fit. Thinspo users promote a lifestyle of "pro-ana", meaning pro-anorexic, or "pro-mia", meaning pro-bulimic. On social media sites, where thinspo is most prominently found, these users will post pictures of emaciated, skimpily clothed women with a mantra such as "Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels." Due to the negative psychological effects associated with thinspo, social media sites, such as Instagram and Facebook, have taken measures to ban online thinspo activity (Angyal). However, fitspo, a spin-off of thinspo that promotes a healthy lifestyle, has not been regulated by social media sites.

Fitspo is highly popular and prominent online, especially on social media sites. Fitspo serves to motivate its viewers to be healthier by working out and eating nutritious foods. However, fitspo contains many obvious similarities to thinspo, which has many known negative psychological effects. Therefore, there is currently an opposing push from the online community with concerns that fitspo is harmful.

Concerns regarding fitspo are numerous, but one of the major apprehensions is the fueling of an obsession, potentially leading to an eating disorder. Take, for example, Sheena Lyonnais, an average American woman in her 20's with a goal to get fit and improve her health. That's when Lyonnais stumbled upon fitspo online. She began viewing various forms of fitspo and even started her own fitspo blog on Tumblr, a social media site that allows users to post multimedia on their individual blog page. Soon, Lyonnais found herself spending hours blogging pictures of women's bodies, always comparing herself to them. She felt that although she was running every day and eating healthy, it wasn't enough in comparison to the women in the pictures. As a result, Lyonnais began religiously tracking her workouts and calories. She amped up her training sessions and cut her calories back, until she was eating a mere 1000 calories per day. Lyonnais realized she was on the path to developing an eating disorder, so she deleted all of her online fitspo activity. Her story didn't end in an eating disorder, but it shows that fitspo has the potential to be psychologically damaging by causing women to view themselves and their bodies as less valuable. In fact, Claire Mysko, who oversees teen outreach on behalf of the National Eating Disorders Association, stated, "We are, as a culture, so obsessed with 'health,' but there's a lot of stuff that comes under this umbrella of health obsession that actually is quite unhealthy" (Adams). Mysko brings attention to how our culture's obsession with dieting and exercise has morphed into the mindset of weight loss and physical appearances, rather than overall health and body acceptance. To continue her argument with regard to fitspo, Mysko says, "Most of this content [fitspo] is not promoting self-acceptance. It's saying, 'You're not good enough and you have to do this to get better" (Adams). Her statement highlights fitspo's problematic nature of initiating body comparisons and promoting fitness at all costs, a mindset that can trigger an obsession and possibly lead to an eating disorder.

In fact, this mentality of fitness at all costs is becoming more prevalent, not just among young girls, but also among adolescent boys, and is resulting in unhealthy behaviors. Young males' unhealthy diet and exercise extremes have been driven by the media's advertisement of a muscular, fit body type. More specifically, this is found online in an intensified form as fitspo. Males have been using fitspo online in the same manner as females have used thinspo. On bodybuilding forums, adolescent males share weight-lifting regimens and compare body fat percentages. On social media sites, such as Tumblr or Facebook, young men post pictures of other men's lean, muscular bodies as inspiration and motivation (Quenqua). Often, these inspirational or motivational posts contribute in driving young males to unhealthy, extreme behaviors to obtain the physique modeled in the pictures. When extreme forms of fitness behaviors are examined in males instead of females, an increasing prevalence of a different risky behavior, namely the use of supplements and steroids, is observed. A team led by Marla Eisenberg, a pediatric psychologist, conducted a study in 2012 to analyze the prevalence of muscle-enhancing behaviors. The study's results showed that 40 percent of middle school and high-school boys regularly exercise to build muscle. Of these young males, 38 percent use supplements and 6 percent use steroids (Eisenberg, Wall, and Neumark-Sztainer 1021). Supplements and steroids pose health issues, especially when taken in large amounts or to replace meals. Dr. Shalender Bhasin, the chief of endocrinology, diabetes, and nutrition and the Boston Medical Center, explains "The problem with supplements is they're not regulated like drugs, so it's very hard to know what's in them" (Quenqua). He goes on to say that many supplements may contain anabolic steroids, which are often used individually or in addition to supplements. The primary health threat of anabolic steroids is that they stop testosterone production in men. This results in serious withdrawal problems when young, still-growing males try to stop using these steroids (Quenqua). Although supplements and steroids pose completely different health risks, these substances are just as harmful to one's health as eating disorders.

Although statistically more males use supplements and steroids than females, these substances still have adverse effects on women's health (Grogan 48). Currently, 21 percent of women use supplements and 5 percent use steroids to aid in muscle growth and fat loss (Eisenberg, Wall, and Neumark-Sztainer 1021). It is possible that these numbers could rise in the near future due to the more complicated, harder to achieve body type idolized in the media. Eisenberg explains this more complex pressure by stating, "The model of feminine beauty is now more toned and fit and sculpted than it was a generation ago… It's not just being thin. It's being thin and toned" (Quenqua). This crossover of being thin but muscular makes the ideal body more difficult to obtain and maintain. Many women could begin turning to unhealthy and extreme methods, such as supplements and steroids, to build muscle and lose fat while maintaining an unhealthily thin figure. Women who have previously undergone extreme methods, such as starvation or purging, to obtain a thin body type could be more likely to begin experimenting with supplements and steroids or forming an obsession with fitspo. All of these methods are detrimental to a woman's physical and psychological health, and should be regarded as equally hazardous and risky.

The public has shown an overwhelming concern regarding the effects of fitspo, especially due to its striking similarities with thinspo. Many studies have evaluated thinspo and given evidence to establish a correlation of viewing media, particularly media images of thinness, and body dissatisfaction in young adults (Homan et al. 50). Unfortunately, the scholarly field has conducted little research regarding exposure to images of fit physiques, or fitspo. However, the studies that have been performed have opened doors to the complexity of the situation.

A study conducted by a team of psychologists analyzed the effects concerning body satisfaction after exposure to images of athletic models that were either thin or normal-weight. The study's results showed that viewers of the images of thin, athletic models reported an increase in body dissatisfaction. In contrast, viewers of the images of normal-weight, athletic models did not report any greater body dissatisfaction than the control group. This evidence supports that an ultra-fit physique alone does not cause body dissatisfaction. Instead, the thinness of the models is suggested to be the driving factor (Homan et al. 53-54). Based off these findings, fitspo using normal-weight models does not cause negative psychological effects. In contrast, fitspo using skinny yet athletic models could cause an increase in body dissatisfaction, due to the thinness of the models. However, the two types images tested in this study were both of "athletic" women and merely differed in the level of adiposity, leaving a necessity for further testing.

In a study expanding upon the research performed by Homan's team, two psychologists analyzed the effects regarding women's body satisfaction after viewing images of women's bodies varying in amounts of muscularity, as opposed to adiposity. Images were classified into three groups: thin, thin and muscular, thin and hypermuscular. After viewing the thin and thin-muscular images, which are both representative of the modern ideal body types, women's body satisfaction decreased. In contrast, after viewing the thin-hypermuscular images, women's body satisfaction did not change (Benton and Karazsia 22). This study gives evidence that thinspo and fitspo, in the form of thin and toned bodies, are detrimental to women's body satisfaction and psychological health. Additionally, this study supports that fitspo, in the form of muscular, normal-weight women, is not detrimental to women's body satisfaction and psychological health.

This research aimed to assess fitspo as a therapy to eating disorders. In order to do so, the growing sociocultural issues of body dissatisfaction, media influence, and eating disorders were addressed. Furthermore, a correlation was established among these three problems. The media's overpowering promotion of an idealistically thin yet muscular female physique was associated with increased body dissatisfaction. In turn, body dissatisfaction was shown to lead to unhealthy behaviors such as the use of steroids and/or supplements, fad dieting, and extreme caloric restrictions. The latter two are indicative behaviors of eating disorders. These problems were then addressed in relation to new online communities promoting "thinspo" and "fitspo." Thinspo fuels an eating disorder by promoting a "pro-ana" or "pro-mia" lifestyle, whereas fitspo promotes a healthy lifestyle. However, due to their striking similarities, the public began voicing concern that fitspo, like thinspo, could be detrimental to one's psychological health. In response, scholarly research showed that images of thin women, muscular or not, cause a decrease in body satisfaction. However, images of normal-weight, muscular women—a form of fitspo—do not have an effect on body satisfaction.

Based on this research, fitspo was determined to hold the potential to be either negatively or positively influential based on particular factors, namely the type of fitspo being viewed and the individual person. Each individual is different, especially in regard to self-confidence and body satisfaction. Therefore, each person will respond differently to fitspo. Those who have previously taken drastic measures to achieve a particular body type may respond to fitspo in an unhealthy manner, forming an obsession. However, those who are self-confident and have a healthy body image may respond to fitspo more positively. The response to fitspo is also based on the type of fitspo being viewed, namely whether the physique is thin or normal-weight. Fitspo of thin models will cause negative psychological effects, especially on those with eating disorders. However, fitspo of healthy and confident average-weight women will motivate viewers to truly lead a healthier lifestyle by exercising, eating nutritious foods, and loving their body. This latter type of fitspo holds the potential to be utilized as a therapy to eating disorders.

Furthermore, fitspo has the potential to shift our culture's view of the ideal female physique. Currently, our societal views of feminine beauty are skewed and unhealthy. However, fitspo of healthy-weight women who are confident and have a positive body image could inspire others to be healthier too. This form of fitspo fits the true meaning of "fitness inspiration". It promotes health, body-acceptance, and what our modern society needs above all else—self-love.

Works Cited

Adams, Rebecca. "Why 'Fitspo' Should Come With A Warning Label." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 17 July 2014. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Angyal, Chloe. "The 'Thinspiration' Behind an Impossible Ideal of Beauty." Web blog post. The Nation. The Nation, 23 Apr. 2013. Web. 28 Feb. 2015.

Benton, Catherine, and Bryan T. Karazsia. "The Effect of Thin and Muscular Images on Women's Body Satisfaction." Body Image 13 (2015): 22-27. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Derenne, J. L., and E. V. Beresin. "Body Image, Media, and Eating Disorders." Academic Psychiatry 30.3 (2006): 257-61. Web. 28 Feb. 2015.

Eisenberg, Maria E., Melanie Wall, and Dianne Neumark-Sztainer. "Muscle-enhancing Behaviors Among Adolescent Girls and Boys." Pediatrics 130.6 (2012): 1019-026. Web. 10 Apr. 2015.

Grogan, Sarah. Body Image : Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children. Florence: Routledge, 1999. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 15 March 2015.

Homan, Kristin, Erin Mchugh, Daniel Wells, Corrinne Watson, and Carolyn King. "The Effect of Viewing Ultra-fit Images on College Women's Body Dissatisfaction." Body Image 9.1 (2012): 50-56. Elsevier. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

National Eating Disorders Association. "Types & Symptoms of Eating Disorders." National Eating Disorders Assocation. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Apr. 2015.

Polivy, Janet and C. Peter Herman. "Sociocultural Idealization of Thin Female Body Shapes: an Introduction to the Special Issue on Body Image and Eating Disorders." Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 23.1 (2004): 1-6. ProQuest. Web. 4 Mar. 2015.

Quenqua, Douglas. "Muscular Body Image Lures Boys Into Gym, and Obsession." New York Times. New York Times, 19 Nov. 2012. Web. 28 Feb. 2015.

Sivert, Sejla S., and Osman Sinanovic. "Body Dissatisfaction—Is Age a Factor?" Philosophy, Sociology, Psychology and History 7 (2008): 55-61. Web. 28 Feb. 2015.