Trigger Warning: Mentions of Adolescent Drug Overdose and Suicide

My parents have always been rather permissive; growing up, as long as I checked in at the beginning and end of the day, I could go wherever I wanted in the middle. There were only a handful of rules: be home before dark, don’t go anywhere with strangers, and don’t go into inner city Baltimore.

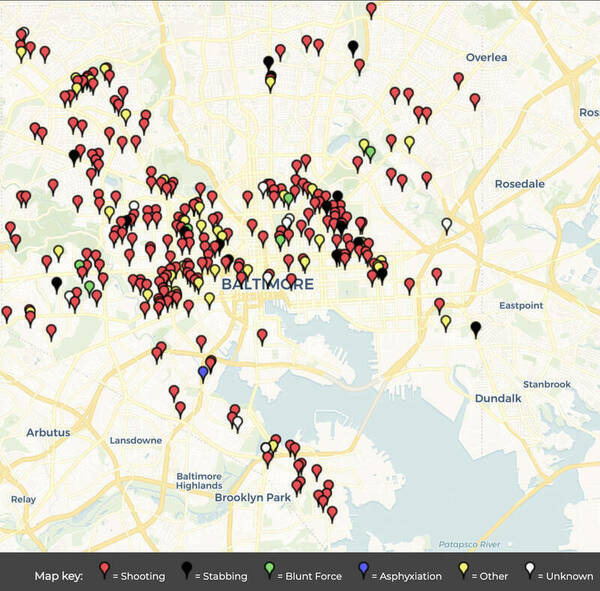

While the last rule may appear dramatic, it isn’t without reason. Baltimore is ranked the fourth most dangerous city in the country by CBS (Fieldstadt), with nearly 1,900 violent crimes per 100,000 citizens each year; that statistic doesn’t even include the cases of property damage, larceny, burglary, or vehicle crimes (“Baltimore, Maryland”). To the right is a map of the city compiled by the Baltimore Sun, a local newspaper, with each of the over 300 pins representing a murder committed since the beginning of this year (Baltimore Sun).

I have not met a single person my age who grew up in or around Baltimore without at least one horror story involving crime, drugs, self-harm, or suicide. I could personally name half a dozen friends who have taken opioids, cut their wrists, or attempted suicide at least once. Trauma like this should be seen as a tragedy for any child, but in Baltimore, it borders on the norm. In an article titled “Baltimore Children ‘Facing a Mental Health Crisis,’” Stacey Jefferson, a journalist for the Baltimore Sun, explains the situation perfectly; “Imagine a 7 year old undergoing—up close—a violent incident that takes the life of a loved one. Now imagine that same child experiencing something similar multiple times during their childhood. This is not uncommon for many of our children and youth in Baltimore City” (Jefferson). Jefferson categorizes childhood encounters with extreme violence, neglect, sexual assault, or substance abuse as ‘adverse childhood experiences’, and states that “39 percent of Baltimore City adults had experienced one or two ‘adverse childhood experiences’ as kids . . . while 42 percent had gone through between three and eight of those experiences in childhood—by far the highest numbers in the state” (Jefferson). To restate that statistic, only nineteen percent of children who grow up in Baltimore do so without an adverse childhood experience.

In such a traumatic environment, mental health care becomes an absolute necessity, one that most Baltimore schools fail to provide. The city’s schools have an average student to counselor ratio of 900:1, six times the recommended national ratio (Richman). Beyond that, there is little to no mental health education in schools due to long standing stigma and a severe lack of funding for mental health care. This lack of support leads students to seek alternative outlets, which often manifest in the use of drugs, more specifically, opioids. Baltimore’s opioid epidemic began back in the eighties, and has only intensified with every passing year, leading to the modern situation where there are six overdose deaths per thousand citizens each year (Choo). Underfunded social work has plagued the entire state since the nineties, but has worsened dramatically since the beginning of the pandemic, with many of the state's social workers being laid off amidst budget cuts (Richman). What kind of message does it send to students when one of the first things sacrificed in times of strife is the support system built to help them deal with strife itself? How can a community abandon the next generation and expect anything other than high dropout rates, higher crime rates, more drug usage, and more student suicides?

It is obvious that changes need to be made for the health and safety of Baltimore’s next generation. How, then, do we support Baltimore youth in a system that lacks counselors to hire, lacks funding to hire them, and hosts a strong stigma against using professional mental health services? One possible solution is a citywide implementation of the Student Listener program, a concept created by the New Hampshire boarding school Phillips Exeter Academy. Self-described as a system built to support any mental health issue, “whether it’s academic, social, emotional or health-related,” (“Student Support”) the Student Listener program provides specialized training to volunteer students in order to create a first line of defense against mental health crises. Students apply to become Students Listeners for their school, and those who are accepted undergo twice weekly meetings with a trained professional to get advice and learn how to better support their peers. Their job is to act as a casual and community-based form of therapy and mental health support to the student body, something that fellow students are in a perfect position to do. Above all, they would still be students, and as such can provide a level of kinship and relatability no adult therapist could hope to match. During my first year at Phillips Exeter, I lost my uncle to suicide and my grandfather to a stroke within the span of a week, a series of events that sent me into a state of mental decline, and I would not have been able to finish that year without the help of the Student Listener who lived down the hall. While I was unsure whether or not to seek professional help, or even how to do so, I knew I could count on that Student Listener to be there as both a trained therapist and a close friend. Implementing a Student Listener program in Baltimore would work to combat the mental health crisis by providing a community-based mental health resource that costs less, requires less trained counselors, and will enable students to get the help they need in a culture stigmatized against mental health care.

While the Student Listener program itself is not yet widespread, its style of community-based support is the foundation of many modern healthcare models. One such model, called the Mental Health Collaborative Care Model, is the result of decades of psychological and civil research with the goal of creating an optimized system of mental health support. According to Mental Health Collaborative Care and its Role in Primary Care Settings, one of the greatest failures of modern mental health care is that it tends to “prioritize the treatment of acute symptoms over the need to properly manage individuals with chronic conditions,” (Goodrich) and, as such, does nothing to prevent further incidents. This is a trap that the Baltimore school board often falls into with their mental health plans—specifically their suicide prevention plans—for example when they decided to use software to monitor student’s home laptops for signs of imminent suicide risk, sending the police to the student’s doorstep if the tracker determined the student was in danger (Goodrich). While this invasion of privacy may prevent a few suicides with last minute intervention, it does nothing to address the issues that drive students to the point of suicide becoming an option.

The most important step in preventing suicide is to provide a community-based support system that enables people struggling with mental illness to get psychological help before they become a suicide risk. The Community Care Model stresses the usage of “community resources outside of primary care,” (Goodrich) and the Student Listener program is a resource directly built from the school community. In my own personal experience, while I was hesitant to reach out to mental health professionals due to internalized stigma from growing up in the Maryland area, it felt natural to ask the Student Listeners in my dorm for help. In a study conducted specifically about substance and opioid abuse related therapy, it was discovered that more casual, ‘low structure’ counseling from friends or less-professional sources has better results for patients who are not suffering from extreme mental illness but instead struggling with trauma or lesser psychological issues (Gottheil). Beyond that, students are in a perfect position to see what health professionals can often miss. In a study conducted by the American Journal of Public Health, it was found that 13% of students who had a significant mental health problem were able to be identified by members of the community while simultaneously being overlooked by suicide screening tests (Scott). While not a replacement for all professional services, there is no denying that community-based care has benefits over the more traditional professional route. The Student Listener program would provide Baltimore schools with a system that works to bypass stigma while providing support to students before their issues become critical.

A Student Listener program would not only be effective, but would also be relatively easy to implement. While Baltimore’s student to counselor ratio of 900:1 is nowhere near enough to cover the student body with a normal program, a single counselor could be in charge of educating dozens of Student Listeners who, in turn, would be able to support a larger number of students. Phillips Exeter utilizes over fifty Student Listeners that are all managed by a small team, and, in my experience, that number of Student Listeners has proved more than enough to cover the school’s population of over one thousand students ("Student Support"). If a standardized course was created by the Baltimore school board to educate the volunteers, the counselors themselves would have to do little extra work besides familiarizing themselves with said course and meeting with the Listeners for a few hours a week. As such, beyond the initial monetary cost of creating a standardized education program, the implementation of a Student Listener program would require little more than proper utilization of the resources already available to Baltimore schools, allowing it to work despite the lack of funding and national counselor shortage.

The greatest difficulty in implementation would undoubtedly be social pushback. Admittedly, the idea of children being cared for by other children can be a hard pill for many parents to swallow. “How could a student be trusted to deal with something that serious? Kids shouldn’t have to deal with suicide” was an objection I have heard from adults whenever I mention the student listener program. This is, of course, a fair point, but my answer is immediate: “Is that not what we already do?” Students already live through trauma, hardship, and mental illness. To say that students are not capable of listening to and taking care of each other is to ignore the fact that they have already been counting on their friends to help with trauma for years. One would struggle to find a single student who had not confided in a peer or acted as a shoulder to cry on. All the Student Listener program does is train those friends to be able to better care for each other and to give them the backing of a professional psychologist.

There is, of course, the question of “who looks after the Student Listeners?” The answer to that is the rest of the Student Listener program. In implementing this program within Baltimore, the main purpose of the weekly meetings would be to have the Student Listeners check in with the psychologist in charge of the program and with each other in order to decompress, get advice, and, most importantly, be supported themselves. The Student Listeners would be actively encouraged to take as much time and space as they need for their own mental health, as the program is, at its base, a volunteer program. The goal of the program is to ensure that students have every resource they need to help each other succeed, and that includes ensuring that the Listeners themselves are cared for.

The most important step in implementation is to get the program certified and enforced by the Baltimore and Maryland school boards, a task that is now more possible than ever. In light of declining student mental health during the pandemic, both entities have shown a recent and uncharacteristic willingness to partake in mental health initiatives. Earlier this year, a Maryland law was passed that allows minors of ages twelve or older to seek mental health care without requiring consent or involvement from their guardian (“New Maryland Law”). This allows students who require treatment to find it more easily without the stigma associated with asking adults for approval, although it does nothing to address the lack of counselors available to these students. Also within the year, the state of Maryland has proposed a law that would require schools to allow students a certain number of guaranteed mental health days per year. These days could be taken without explanation or reasoning, encouraging students to take the time they need to heal and care for their mental health. Students are allowed to go over the baseline allotment of days, but they are automatically recommended to a counselor if they do so (Hindle). While in theory this automatic recommendation would bring struggling students into the mental health care system, it could also serve as a deterrent to taking any extra mental health days because of the same stigmas that cause students to avoid professional counseling currently. These are important steps to lowering the bar for mental health care access, but they don’t solve every issue on their own. Both laws require the involvement of professional counselors, limiting their effectiveness in the current shortage, but this flaw could be fixed by implementing these laws in tandem with the Student Listener program and allowing the Student Listeners to work as a substitute for a counselor if they so choose. That way, students would be able to take those extra mental health days without the stigma associated with seeing an adult, and there would be enough resources to cover the influx of students brought into the mental health care system. There is no single action that can fix the entire mental health crisis, but these governmental changes in tandem with the implementation of a Student Listener program would be a great place to start.

Growing up in Baltimore is a traumatic experience for most children, and while changing the state of the entire city will take decades of gradual work, changing the way its students are supported and cared for can be done within the year. The implementation of a Student Listener program would be an actionable and effective step towards solving the mental health crisis due to the plethora of issues it solves, from providing de-stigmatizing, community-based care to lessening the counselor shortage in inner city schools. When I was at my lowest point in Freshman year, I considered dropping out of school then and there; between the stress of advanced classes and lost family members, I was unable to cope with day-to-day life. I try not to think about what would have happened to me if I had, in fact, dropped out, but I think that reality is important to face: I would have ended up like all of my friends who dropped out back home, leaning on self-destructive coping mechanisms and wasting my life. Exeter’s Student Listener program kept me from reaching that point, and implementing its likeness in Baltimore has the potential to do the same for almost eighty-thousand students ("City Schools"). The Student Listener program is the next step in supporting our youth, a goal worth any cost, and all it takes is the proper utilization of current resources. If the Student Listener program were to be standardized and implemented citywide, it would not only work to secure the mental health of the current student body, but, by supporting the next generation, it would help to secure the future of Baltimore as a whole.

Works Cited

“About Us.” Phillips Exeter Academy, https://www.exeter.edu/about-us.

“Baltimore, Maryland.” Best Places, Sperling's Best Places, https://www.bestplaces.net/crime/?city1=52404000&city2=52453325.

“Baltimore City Homicides.” The Baltimore Sun, https://homicides.news.baltimoresun.com/.

Choo, Shelly, and Leana S Wen. “Baltimore Citywide Engagement of Emergency Departments to Combat the Opioid Epidemic.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 108, no. 8, 2018, pp. 1003-1005, doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304551.

“City Schools at a Glance.” Baltimore City Public Schools, https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/district-overview.Goodrich, David E., et al. “Mental Health Collaborative Care and Its Role in Primary Care Settings.” Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 15, no. 8, 2013, pp. 1–12, doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0383-2.

Gottheil, Edward, et al. “Effectiveness of High Versus Low Structure Individual Counseling for Substance Abuse.” The American Journal on Addictions, vol. 11, no. 4, 2002, pp. 279–90, doi:10.1080/10550490290088081.

Fieldstadt, Elisha. “The Most Dangerous Cities in America, Ranked.” CBS News, 9 Nov. 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/the-most-dangerous-cities-in-america/51/.

Hindle, Tom. “Maryland Bill Would Give Students Mental Health Days off, No Need for Doctor's Note.” NBC4 Washington, 9 Feb. 2021, https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/changing-minds/maryland-bill-would-give-s.

Jefferson, Stacey. “Baltimore Children 'Facing a Mental Health Crisis'.” Baltimore Sun, 6 May 2019, https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/op-ed/bs-ed-op-0507-school-supports-20190506-story.html

Jones, Cheryl. “New Maryland Law Allows Minors Ages 12 and Older to Consent to Mental Health Treatment without Parental Consent.” JD Supra, 4 October 2019, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/new-maryland-law-allows-minors-ages-12-9957173/.

Richman, Talia. “Baltimore Sees Decline in School Counselor Positions,” Baltimore Sun, 1 March 2018, https://www.baltimoresun.com/education/bs-md-ci-sun-investigates-school-counselors-20180301-story.html.

Scott, Michelle A., et al. “School-Based Screening to Identify At-Risk Students Not Already Known to School Professionals: The Columbia Suicide Screen,” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 99, no. 2, 2009, pp. 334-339, doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.127928.

“Student Support.” Phillips Exeter Academy, https://www.exeter.edu/community/student-support.