Growing up on the banks of the Kennebec River in east Bowdoinham, I lived the first eighteen years of my life about half a mile as the crow flies from the old “Lower Road” railroad corridor, which cuts a gently curving path around Merrymeeting Bay and up the river to Augusta. For several years as a child, I was obsessed with trains and imagined myself growing up to be a conductor on this route, directing and riding the Amtrak Downeaster back and forth from Brunswick to Augusta all day. As any Bowdoinham, Richmond, Gardiner, or Topsham resident can attest, this portion of the Lower Road runs through a gorgeous rural landscape of forests, fields, swamps, rivers, and quaint downtowns.

Unfortunately for my six-year-old self, what I didn’t realize was that the Brunswick-to-Augusta corridor actually had not been used for commercial rail service since 1986, well before I was even born. And over decades of abandonment, it has deteriorated into a depressingly poor condition. Walking along any length of the corridor you will see hundreds of broken or rotting crossties, heavily rusted rails and fasteners, and almost no complementary infrastructure. The line’s bridges and overpasses are similarly hazardous: for instance, near where I live in east Bowdoinham, the railroad bridge over the Abagadasset River is dangerous to traverse on foot, let alone by a several-hundred-ton train. A few miles north in Richmond, the rail overpass across Route 24 had to be removed after being damaged numerous times by tall vehicles (Lowell). And at the northern end of the line, the low-clearance trestle over Water Street in Augusta poses a similar problem (Edwards).

The time has come for the Lower Road to become something new. Since 2008, the towns of Bowdoinham, Topsham, Richmond, and Gardiner have formally supported rehabilitating the dilapidated portion of the line between Brunswick and Gardiner into a twenty-five-mile rail-trail that would be known as the Merrymeeting Trail (“Merrymeeting Trail—Connecting”). If constructed, this rail-trail has the potential to be a highly valuable economic and recreational resource for the communities of Sagadahoc County.

Some might ask—what exactly do I mean by a “rail-trail”? The Rails-To-Trails Conservancy, a DC-based nonprofit organization that advocates for the development of rail-trail systems across the US, offers this definition:

Rail-trails are multi-purpose public paths created from former railroad corridors. These paths are flat or gently sloping, making them easily accessible and a great way to enjoy the outdoors. Rail-trails are ideal for many types of activities—depending on the rules established by the local community—including walking, jogging, bicycling, wheelchair use, inline skating, cross-country skiing, and horseback riding. (“About Rails-To-Trails Conservancy”)

Rail-trails first became popular during the decline of passenger and freight rail in the late-twentieth century, as municipalities took advantage of the opportunity to convert unused rail corridors into a new, sustainable asset for their community. One might say that the rail-trail train has been gaining steam ever since (pardon the pun!). In fact, the Rails-To-Trails Conservancy reports that there are currently over 24,000 miles of rail-trails nationwide, more than half the mileage of all of America’s interstate highways (“About Rails-To-Trails Conservancy”). Maine alone has thirty-seven distinct rail-trails that cover about four-hundred miles (“Maine Rail-Trail Plan 2020-2030”). One of these trails, the Kennebec River Rail Trail, covers the 6.5-mile segment of the Lower Road corridor from downtown Gardiner through Hallowell to the waterfront in Augusta and is a highly popular recreation area for the surrounding communities.

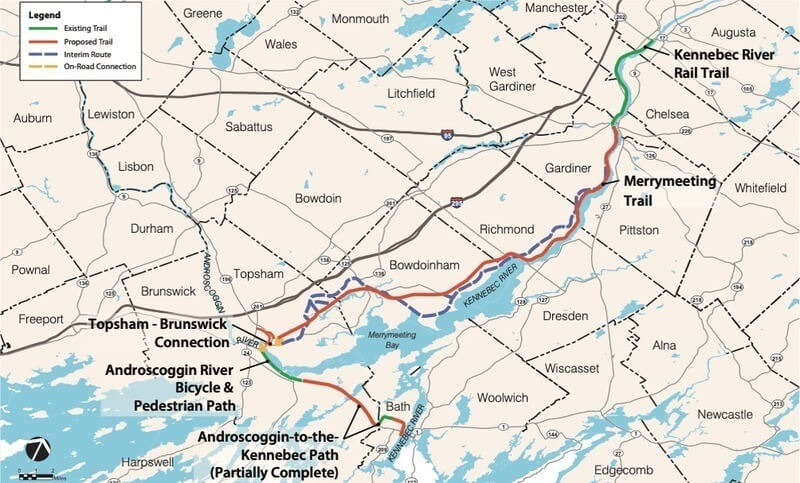

If constructed, the Merrymeeting Trail (sometimes abbreviated as the “MMT”) would actually connect at its northern terminus to the Gardiner end of the Kennebec River Rail Trail. It would then follow the Lower Road corridor down through South Gardiner, Richmond, and Bowdoinham into Topsham, where a brief on-road connection would link it to the 2.6-mile Androscoggin River Bicycle Path. Together, these three paths would form the majority of the Capital to Coast Trail, an envisioned forty-mile multi-use trail facility (see Fig. 1). The Capital to Coast Trail would stretch from Augusta along the Kennebec and around Merrymeeting Bay to the waterfront in Bath, and is one of only a handful of trails to be designated as a trail of statewide significance by the Maine Department of Transportation (“Timeline of the Merrymeeting Trail”).

As a well-situated and accessible rail-trail, the Merrymeeting Trail would provide an opportunity for substantial health benefits in the population in an era where outdoor recreation and exercise has become critical to our nation’s battle against the health issue of physical inactivity. Rail-trails provide people with safe and scenic places for people to exercise that they might not otherwise have access to, which has been shown to significantly increase activity levels among sedentary and already-active people alike (Abildso et al.). Further studies show that this has the effect of reducing the massive healthcare costs associated with a sedentary lifestyle by amounts that far exceed the actual cost of constructing the trail (VanBlarcom & Janmaat), and is a more cost-effective method of encouraging physical activity than other public health programs (Abildso et al.). That is to say, all the data suggests a rail-trail like the proposed Merrymeeting Trail would be worth the investment due to its health benefits alone!

The Merrymeeting Trail also has the potential to decrease health risks in an entirely different way, namely by reducing the danger of motor vehicle collisions with pedestrians or cyclists, an issue that has actually been declared pandemic by the World Health Organization. My father has always been particularly concerned about this, and throughout my teenage years, I remember he would stress out and insist that I wear reflective gear and a flashing headlamp every time I went out for a run on the road. Though that may sound ridiculous, looking back, I’m rather appalled that he had to fear for my life every day when there was a perfectly safe off-road corridor half a mile away, just waiting to be redeveloped and used as a rail-trail. This is no joke; thousands of Americans die or are seriously injured on the roads each year because of motorist negligence or unsafe infrastructure, while rail-trails provide a “gold standard” in terms of safe off-road alternatives for people to engage in recreational exercise or active transportation (“Addressing Safety and Health Concerns”). Skeptics can brush off my anecdote as just that—an anecdote—but the point that it makes is simple common sense.

Rail-trails have plenty of advantages beyond their health benefits, too. For a relatively long, rural rail-trail such as the Merrymeeting Trail, the overall benefits to welfare of its users are particularly high. This figure is also referred to as the “net economic value” of the trail,[1] which studies indicate tends to number in the millions of dollars per year (Siderelis & Moore; Bowker et al.). Just like the health benefits mentioned above, the annual net economic value of a rail-trail tends to quickly exceed the trail’s cost of construction within a couple years—and this rings especially true for the Merrymeeting Trail. The Lower Road corridor it would be built on is, of course, ideally located for scenic outdoor recreation, and it would also be easily accessible for the vibrant, trail-hungry running and biking communities in Topsham and Brunswick, not to mention active commuters who live in the bedroom communities between Augusta and the Bath-Brunswick area.

Even beyond those surface-level observations, there are other present-day factors that indicate the Merrymeeting Trail would be heavily used and have multifaceted value to its users. Looking on a national scale, the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically increased America’s demand for outdoor recreation opportunities as people seek safe, socially-distanced ways to get out of their houses and decompress through exercise (Tate). According to a Rails-To-Trails Conservancy study in July 2020, with trails being one of the only places that remained open to the public throughout the pandemic, trail-use across the country had risen over 200% since one year before (Brooks). 46% of respondents in the same study also indicated that “having access to open spaces has reduced their stress levels during the pandemic” (Brooks). Clearly, there’s something to be said for the mental/emotional benefits of outdoor exercise as well as its impact on physical health, and the current moment presents a win-win opportunity for the MMT’s surrounding communities to reap these benefits along with attracting tourism and economic activity to the area.

Tourism, you say? In fact, the tourism impact of rail-trails like the Merrymeeting Trail is just as well-documented as their health and welfare benefits. Due to being built on old railway beds, rail-trails generally have relatively gentle gradients, firm surfaces, no sharp turns, and ample width—all features that help make them an attractive recreational tourism product (Reis & Jellum). The scenic, charmingly rustic terrain that the Merrymeeting Trail would run through would only enhance its tourist draw, as would its adjacency to important cultural sites such as Swan Island and Gardiner’s downtown district, both of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Consider a 2007 study of the Virginia Creeper National Recreation Trail, a rail-trail comparable in length and geographic location to the Merrymeeting Trail, which found that almost $1.6 million in local economic output was generated for every 1,000 tourist visits (Bowker et al.). It’s highly likely that MMT tourism would have a similar impact on economic activity in Sagadahoc County, benefiting dozens of small businesses in the downtowns of Brunswick, Topsham, Bowdoinham, Richmond, and Gardiner to the tune of millions of dollars. Combined with the Kennebec River Rail Trail to the north, this part of the Capital to Coast trail system would serve over 66,000 residents in its communities alone, but it would also be within a 30-mile radius of 46% of the state’s population, making it well-located for intrastate tourism (“Merrymeeting Trail —Feasibility Study”).

But let’s put all these tremendous benefits to the side for a second. In a time when town and state budgets are tight due to the COVID-19 recession, many might—understandably—raise concerns about the initial costs of an investment project such as the Merrymeeting Trail. Indeed, a 2011 feasibility study looked at the cost of constructing a trail next to the Lower Road railroad bed—this is what’s known as a “rail-with-trail” system—and found that it would amount to about $50 million due to “significant physical challenges and environmental constraints” such as narrow bridges and embankments (“Merrymeeting Trail—Feasibility Study”). $50 million is no insignificant sum, even though, as I’ve already detailed, the cumulative annual benefits that the trail would bring in terms of health, welfare, and tourism would probably rapidly outstrip that initial cost.

But crucially, the cost of building a normal rail-trail—one where the old railroad tracks are actually removed and replaced with a paved or gravel path—would likely come to a far lower number than $50 million. The same 2011 study of the MMT indirectly pointed this out, saying, “If the railroad corridor consisted of a double track for its entire length (only about 4 miles is actually double track today), removing one of the rail lines and building an unpaved trail would cost about $7.7 million, or about $0.3 million/mile” (“Merrymeeting Trail—Feasibility Study”). Thus, it follows that construction of the Merrymeeting Trail along the single track for the full twenty-five miles would come at a similar expense. In other words, a traditional rail-trail would be much more cost-efficient than a “rail-with-trail.”

But currently, the Merrymeeting Trail’s official website specifically classifies it as a rail-with-trail project, aligning with the 2011 study (“Merrymeeting Trail—Connecting”). So at first glance, this marriage to creating the MMT as a “rail-with-trail” seems confusing. Since an important aspect of rail-trails’ attractiveness is their cost-efficiency, doesn’t developing a far more expensive path adjacent to the tracks partly defeat the purpose? Clearly, it would be much simpler and cheaper to recycle the rail line itself, with no need for embankments to be widened, additional bridges to be built, or private property along the edges of the corridor to be bought. What oversight is being made here?

The truth is, it’s not really an oversight—it’s more an issue of political machinations. The Lower Road corridor is still owned by the Maine Department of Transportation, which opposes the transition to a rail-trail, citing Maine’s Rail Preservation Act as justification (Shepherd). Therefore, in order to avoid incurring the DOT’s wrath, the Merrymeeting Trail coalition has apparently switched gears and begun pushing for the rail-with-trail option, which would leave the current tracks in place. Yet even this step seems confusingly short-sighted, partly because of the much higher cost of building a rail-with-trail, but also because the same Rail Preservation Act explicitly allows for DOT-owned rail lines to be dismantled and recycled in cases where “removal of a specific length of rail owned by the State will not have a negative impact on a region or on future economic opportunities for that region” (Shepherd). The Lower Road corridor between Brunswick and Gardiner is a prime example of where this exception would apply, since it adds no economic value to the area in its current condition of disuse and disrepair.

Perhaps a healthy dose of public opinion would help convince both the Merrymeeting Trail coalition and the Department of Transportation that a traditional rail-trail is the best use of this corridor. As I already noted, each of the communities along the proposed route of the MMT have already thrown their weight behind the project, but on top of that, statewide public opinion is also heavily in favor of recycling rail corridors as rail-trails. For example, an October 2019 poll found that a whopping 86% of Mainers[2] support converting unused railroad tracks to recreational trails, as long as rails could be reinstituted in the future if rail service becomes a viable option (“Polling shows Mainers”). This only strengthens the case for the Merrymeeting Trail, since restoring commercial rail service on the Brunswick-to-Augusta line is clearly not in the cards for the foreseeable future. Some rail lobbyists may attempt to claim otherwise (Rudolph), but realistically, it’s difficult to imagine that regional demand for passenger rail is high enough to justify the massive cost of renovating all thirty-two miles of the crumbling corridor. There is no sense in letting this valuable resource waste away under our noses just because the DOT and rail lobby want us to keep waiting for a train that might never come.

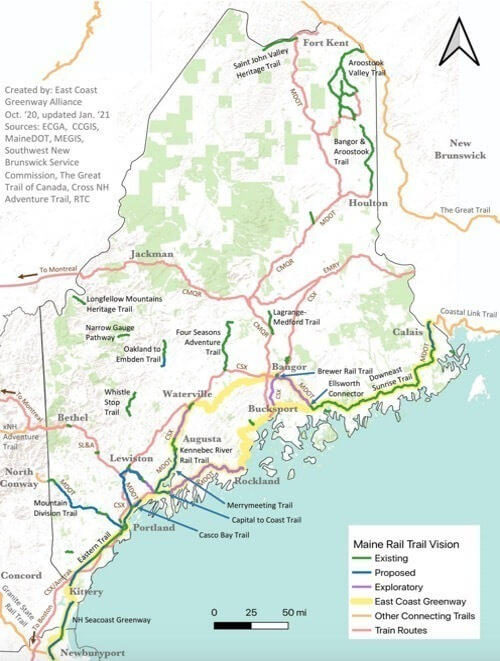

In contrast to rail advocates’ hardline stance, the Maine Trails Coalition has put forth a reasonable proposal for balancing commercial rail service with development of the Merrymeeting Trail and other rail-trail projects. Their vision document for the next decade, the Maine Rail-Trail Plan, calls for “an active transportation network that preserves an inter-urban train corridor, while creating healthy and connected communities throughout the state of Maine through a biking, walking and running rail-trail system” (“Maine Rail-Trail”). Under the Maine Rail-Trail Plan, which is shown in detail in the map below, the state would be able to maintain an active rail corridor along the old Back Road from Portland to Waterville through Lewiston.

This would allow rail connectivity between most of Maine’s largest population centers—Biddeford-Saco, Portland, Brunswick, Lewiston-Auburn, Waterville, and Bangor—for future Downeaster passenger service as well as freight rail (“Maine Rail-Trail”). Meanwhile, much of the Lower Road corridor—including the Merrymeeting Trail segment—could be redeveloped into rail-trails, interconnecting the communities they serve and bringing tremendous health and economic benefits to Sagadahoc, Kennebec, and Cumberland Counties (“Maine Rail-Trail”). It’s a common-sense compromise that both rail and trail advocates can get behind.

The long-term vision that the Maine Trails Coalition lays out is undoubtedly ambitious—besides the MMT, their plan also calls for the development of seventeen other rail-trail projects across the state that would add about 250 miles to the state’s rail-trail network (“Maine Rail-Trail”)—but the groundwork is already laid for the Merrymeeting Trail to become a reality in the near future. With extensive planning and studies of the trail having been completed, and strong public support among the Topsham, Bowdoinham, Richmond, and Gardiner communities, there are only two legislative hurdles left to clear: authorization of the corridor for trail construction, and request for its funding.

The first is covered by a bill in the current session of the Maine Legislature, LD 1370—An Act to Establish So-Called Trail Until Rail Corridors, which is sponsored by Rep. Arthur Bell of Yarmouth (“Action Alert”). This bill would direct the DOT to authorize rail-trail construction on the future Merrymeeting Trail corridor as well as three other major rail-trail projects, with the provision that the state could restore train service on any of these corridors if it is deemed to be in the greater public interest (“Action Alert”). This dovetails nicely with both public opinion and the Maine Railroad Preservation Act, and would allow town and regional authorities to begin the vital step of seeking private, federal, or local funding for trail construction (“Action Alert”).

After this, the second of the aforementioned hurdles would be to request supplemental state funding for the MMT in another bill, but like most states, Maine is currently cash-strapped due to the COVID-19 recession. This makes passage of LD 1370 this session all the more important, so that communities can immediately begin collecting funds from other sources instead of waiting years for state money. However, state funding will likely be necessary further down the road, as a mix of public and private funding would be the best bet to cover the initial cost of building the Merrymeeting Trail (Shepherd). Due to rising construction costs, that expense probably has increased modestly from the $7.7 million figure derived from the 2011 feasibility study (Shepherd).

So an easy way for you, reader, to contribute to the realization of the Merrymeeting Trail is to contact your state representative today and encourage them to support LD 1370! For those who are particularly passionate about the Merrymeeting Trail or about Maine rail-trails in general—like myself—you can get further involved by volunteering with the Maine Trails Coalition, by writing a letter to the editor in your local newspaper to raise awareness and support for rail-trail projects, or even by testifying in support of LD 1370 at its legislative hearing this session. We here in Sagadahoc County have a golden opportunity to recycle a disused resource and turn it into a sustainable, healthy, and culturally vibrant economic asset to the surrounding communities; let’s not wait another second.

[1] In economic terms, the net value of a rail-trail to its users is the consumer surplus derived from a demand for recreational usage measured against users’ travel costs. Thus, it is better classified as a benefit to users’ “welfare” and is distinct from benefits to their health.

[2]This level of support was relatively consistent across political parties, demographics, and regions. The poll was conducted by the Portland-based professional survey group Critical Insights of Maine and consisted of 600 randomly selected registered voters.

Works Cited

Abildso, Christiaan, et al. “Assessing the cost-effectiveness of a community rail-trail in achieving physical activity gains.” Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, vol. 30, no. 2, 2012, pp. 102–113.

“About Rails-To-Trails Conservancy.” Rails-To-Trails Conservancy, www.railstotrails.org/about/.

“Action Alert: Let Unused Rail Corridors Be Used as Trails.” Maine Trails Coalition, 16 Feb. 2021, www.mainetrailscoalition.org/blog/action-alert-allow-unused-rail-corridors-to-be-used-as-trails.

“Addressing Safety and Health Concerns to Increase Active Transportation.” Rails-To-Trails Conservancy, www.railstotrails.org/policy/building-active-transportation-systems/addressing-safety-and-health-concerns/.

Bowker, J.M., et al. “Estimating the economic value and impacts of recreational trails: a case study of the Virginia Creeper Rail Trail.” Tourism Economics, vol. 13, no. 2, 2007, pp. 241–260.

Brooks, Patricia. “New Data Underscores Need for Safe Places to Walk and Bike Close to Home.” Cision PR Newswire, Cision US, 2 July 2020, www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-data-underscores-need-for-safe-places-to-walk-and-bike-close-to-home-301087576.html?fbclid=IwAR13uYfZIPPpeGFf9241hlhZtUCl4_MnZMClBMQKSaQlJBrq3_Z-GQPNlH0.

Edwards, Keith. “Stoutly built ‘Can Opener’ railroad trestle unlikely to be moved in downtown Augusta.” Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel, 18 Sept. 2020, www.centralmaine.com/2020/09/18/stoutly-built-can-opener-railroad-trestle-unlikely-to-be-moved-in-downtown-augusta/.

Lowell, Jessica. “Traffic detour to start Monday in Richmond because of railroad bridge demolition.” Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel, 19 Jan. 2017, www.centralmaine.com/2017/01/19/traffic-detour-starts-monday-in-richmond-while-railroad-bridge-is-torn-down/.

“Maine Rail-Trail Plan 2020-2030.” Maine Trails Coalition, Jan. 2021, static1.squarespace.com/static/5eb4002223a68b4934729073/t/600f014468b6f60a4b0d0f47/1611596101390/Maine+Rail-Trail+Plan+2020-2030+-+Release+1.1+-+1.25.21.pdf.

“Merrymeeting Trail—Connecting Topsham, Bowdoinham, Richmond, & Gardiner.” Merrymeeting Trail, Merrymeeting Trail Blazers, 2018, www.merrymeetingtrail.org.

“Merrymeeting Trail—Feasibility Study.” Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc., 14 June 2011, https://www.americantrails.org/resources/merrymeeting-trail-feasibility-study

“Polling shows Mainers support trails.” Maine Trails Coalition, www.mainetrailscoalition.org/public-opinion.

Reis, Arianne Carvalhedo, and Jellum, Carla. “Rail Trail Development: A Conceptual Model for Sustainable Tourism.” Tourism Planning & Development, vol. 9, no. 2, 2012, pp. 133–147.

Rudolph, Richard. “Maine Compass: Time to extend rail service to central Maine.” Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel, 7 March 2021, www.centralmaine.com/2021/03/07/maine-compass-time-to-extend-rail-service-to-central-maine/.

Shepherd, Sam. “Merrymeeting Trail, connecting Gardiner to Topsham, gets Hallowell council's support.” Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel, 20 May 2019, www.centralmaine.com/2019/05/18/trail-connecting-gardiner-to-topsham-gets-hallowell-councils-support/.

Siderelis, Christos, and Moore, Roger. “Outdoor Recreation Net Benefits of Rail-Trails.” Journal of Leisure Research, vol. 27, no. 4, 1995, 344-359.

Tate, Curtis. “Coronavirus pandemic gives new momentum to bike rides, local trails across USA.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 20 July 2020, www.usatoday.com/story/travel/2020/07/17/coronavirus-pandemic-gives-bike-trails-rides-new-momentum/5434741002/?fbclid=IwAR1ZV6L91kfa3GxWhWbCo5tHkgpzR2izO1ynBIIIqgzyspovqsmAJo_8DY0.

“Timeline of the Merrymeeting Trail.” Merrymeeting Trail, Merrymeeting Trail Blazers, 2018, www.merrymeetingtrail.org/?page_id=114.

VanBlarcom, Brian, and Janmaat, John. “Comparing the costs and health benefits of a proposed rail trail.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, vol. 5, no. 2, 2013, pp. 187–206.

Discussion Questions

1. In this community proposal essay the author draws on local sources and on broader sources used to provide background knowledge or information. Find an example of a source pertaining to the local community and another source that is not specific to the local community. Evaluate each source and discuss how and why the author uses it in his proposal.

2. The author concludes his proposal by addressing his readers with a call to action. What actions does he suggest? What effect does this concluding paragraph have on you as a reader?

3. While a community proposal is most relevant to an audience of community members, what value does this proposal have for readers who are not residents of the area connected to the Merrymeeting Trail? What is something you learned from reading this essay? What broader issues does this proposal essay raise?