In 2010, Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour recommended that the Mississippi State Legislature consolidate all of Mississippi’s public historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) to conserve $35 million in the next year’s state budget. This radical proposition stirred waves of protest from the alumni, faculty, and students of Jackson State University, Alcorn State University, and Mississippi Valley State University. One protester, Percy Norwood, captured the sentiments of the protestors by saying: “We have a responsibility to protect not only our heritage, but our legacy” (Stewart 8). Most activists feel the Governor’s proposal alone created difficulties for the universities, particularly Alcorn State University, which had a very difficult time recruiting a new president since the school’s survival was questionable. Rather than close or merge the HBCUs, the institutions’ affiliates demanded that the state provide more funding to enhance the existing institutions (Stewart 9-10).

Governor Haley Barbour’s proposal may seem like an isolated piece of political radicalism, but fifty years after the March on Washington, it reflects a greater (though highly overlooked) issue for the United States’ 105 historically black colleges and universities: their perceived place in history and post-apartheid America (Wilson 1). A plurality of views exists concerning the roles of HBCUs through history and into the present, especially regarding the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The credit for the movement typically falls on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; yet, some scholars prefer to focus attention on university-based movements. These historians often find at historically black colleges and universities highly aware and active student bodies that contributed nearly all of the “muscle” to their schools’ participation in social justice. Students carried the ultimate burden of the social repercussion that challenged the Caucasian power-hold. Today, the controversy of relevance revolves around the place that HBCUs hold in society, particularly in light of recent, forceful pushes for these institutions to diversify. Some feel that these institutions are abandoning their historic mission to the African American community; others rejoice in the diversification, for they feel that the broadening of student demographics will enhance the schools and keep the institutions relevant (Oslwang 23). Yet others, namely Haley Barbour, feel that, regardless of how these schools adapt to the times or stick to their roots, they have lost their relevance.

The purpose of this paper is to show that historically black colleges and universities played important roles in the Civil Rights Movement (CRM) of the 1950s and 1960s and that the movement has greatly influenced HBCUs to this day regarding all facets of these institutions. I will travel through two hundred years of education history, beginning with the birth of the African American school system, to show HBCUs’ place in history with a special focus on the 1950s and 1960s. Additionally, I will show some changes that have occurred with these schools to illustrate and explain how the CRM carries modern benefits and repercussions for these schools. By the end, I hope to demonstrate these schools’ indispensible pertinence to the Civil Rights Movement and relevance to modern America.

Though my research will discuss the African American higher education system as a whole, I will place particular focus on three HBCUs--Tougaloo College, Spelman College, and Hampton University--to serve as a sort of case study for how these uniquely American institutions instigated and powered the push for racial inequality. This emphasis on three historically influential institutions will uncover the social climate that enveloped and currently envelops HBCUs and forged them into agents of social progress. Though often neglected by historians of the CRM, HBCUs acted as major players on the sociopolitical playing field.

Breaking Bonds and Forming Connections

Though HBCUs emerged as a response to strict segregation, historically black colleges and universities have a long history of social equality and inclusive practices. The bulk of such schools did not appear until just after the Civil War; yet, they existed in small numbers beginning about two hundred years ago. Since their inception, the institutes displayed unbiased admissions policies and fair financial practices towards African Americans, Caucasians, Native Americans, and even women. Religious minorities often received equal treatment at these schools as well. As early as 1830, the African American education system offered educational opportunities and financial assistance to the Choctaw Nation. However, the bulk of these institutions experienced a political tension that rested in what W.E.B. DuBois called the “color line” (Oslwang 73). Before the Civil War, southern states passed legislation to inhibit the education of slaves. Antebellum slave laws criminalized early African American normal schools towards the mid-1800s; so, by the Civil War, essentially no enslaved African American had any “formal” education.

Upon the fall of the Confederacy, the African American community faced a crisis stemming from those laws that forbade the education of slaves: even with an education, the newly emancipated population had virtually no opportunity to escape the socioeconomic circumstances from which it had just been constitutionally freed. As a response, church-linked schools for freed slaves sprouted across the American South (Anderson 12). Southern churches, northern philanthropies, and the government Freedman’s Bureau formed and sustained what were called “Sabbath schools” because they met after church services on Sunday. Although these original institutions endured poor funding and often little staff, the primitive Sabbath schools were the first effective effort to form a universal, state-funded education system in the American South (Anderson, 4). More importantly, the primitive school system symbolized the African American population’s break from the bonds of slavery. According to Walter Allen, “African Americans viewed education as the ultimate emancipator…” (268). As a result, Sabbath schools received unbelievable support from the communities that they served and exploded in size and depth in the decades following the Civil War to become essentially the South’s proto-form of a public education system (Anderson 13-14). Despite their zeal, the communities served by the African American schools still relied heavily on northern philanthropies for funding. As a result, northern agencies gained control over the curricula, and two factions formed over how African American higher education should operate. Samuel Armstrong and Booker T. Washington championed a trade school model, called the “Hampton Model” after the school known today as Hampton University (Page). Other people, namely W.E.B. DuBois, championed the liberal arts model of education to further the emancipation of the individual (Allen 269).

The dispute between HBCU education ideologies lasted through Reconstruction, during which time schools of both views sprouted throughout the South. In 1890, the dispute essentially disappeared. Congress passed the Second Morrill Act, which formed public HBCUs as part of the agricultural and mechanical education system in the United States (Allen 269). Since the states formed these schools under the guidance of the Hampton Model, the need for private African American trade schools vanished. As a result, state-funded schools gravitated towards the trade-school model, and post-1890 private institutions almost universally adopted the liberal arts approach. Some private schools that started as trade schools converted to a more liberal arts curriculum, but vestiges of their Booker T. Washington model persist even to this day (Page). Over the decades following the passage of the Second Morrill Act, public HBCUs in the South became financial dependent upon the white-controlled state governments and operated with uneasiness at their mercy. As a result, the states could threaten financial penalties if public HBCUs tried to upset the segregated order.

In contrast, private historically black colleges and universities, such as the three that I will focus in the next section, evolved relative independence from the Caucasian power-hold due to their starting independently from state funds and sustained financial support from philanthropies, churches, and alumni. Additionally, private HBCUs typically affiliated with a Christian denomination. This religious attachment gave most private historically black colleges and universities automatic networks of religious congregations through which these institutions could spread their agendas. In sum, private liberal arts HBCUs had the social connectivity and active potential to enter the political arena of the mid-twentieth century and attack legal segregation (Lowe 867).

What One Can Do with a School Like Tougaloo

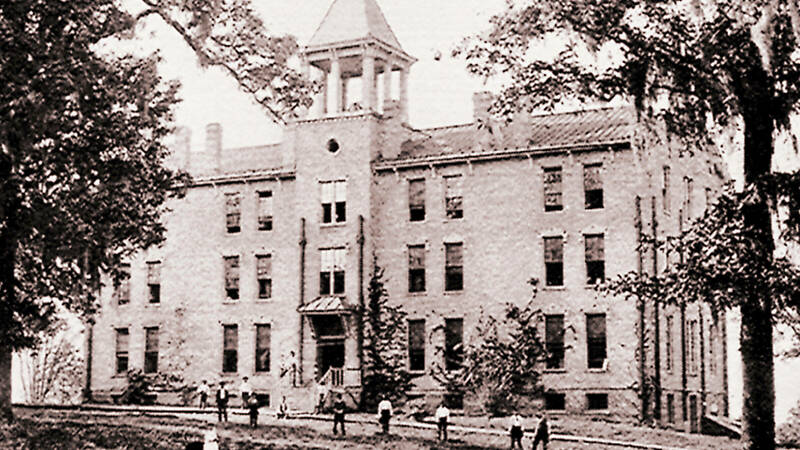

Since its inception in 1871, Tougaloo has held the title of Mississippi’s only private HBCU. Protestant missionaries, in cooperation with the Freedman’s Bureau, founded the school with the idea of using a classical curriculum and an environment where African Americans and Caucasians in Mississippi could work and study together. The result was a highly academic, center-left, HBCU with a curriculum dominated by liberal arts. By the 1930s, Tougaloo received four-year accreditation and quickly rose to the top of the academic rankings. By the 1950s, Tougaloo held the top accreditation rankings, a distinguished faculty, and relative financial stability. Tougaloo had the ability to go after segregation and inequality in the Heart of Dixie (Williamson 556-58).

On its campus, Tougaloo offered “free spaces” where students and faculty could create networks, encourage activism, and bounce ideas with a wall of political protection from the White power system. This service to the CRM was very important because during the 1950s and 1960s the Deep South, particularly Mississippi, “clamped down on anything or anyone seen as promoting dissent, monitored and harassed those who supported racial integration, and attempted to seal the state’s borders from additional ‘outside’ influences” (Lowe 866). Though the Mississippi Caucasian hierarchy exercised brutality and legal ramifications upon dissenters from the segregated norms, authorities and terror organizations could not encroach upon Tougaloo’s campus.

Tougaloo used its legal immunity to sponsor a series of forums to unite the Deep South’s proponents of civil rights. Beginning in the early 1950s, the Tougaloo Division of Social Science sponsored the Social Science Forums to attract intellectuals on the issues of politics, race, popular culture, and government to campus. Ernst Borinski, Chair of the Division of Social Science and a German Jew, conceived and started the programs as opportunities for social experts to discuss current issues and inform the academic community in the Jackson area about the segregated society in which it lived, as well as how to change it. The attendees at these forums included students and faculty of diverse backgrounds since Millsaps College professors and scholars readily participated in the series. These forums fostered a sense of social awareness in the students and staff that attended and placed Tougaloo under the attentive eyes of white supremacist groups, such as the White Citizens’ Council. However, Tougaloo did not shy away from the attention. Rather, the school’s chaplain, Reverend John Mangram, took the institution to a whole new level of controversy by helping to organize the Fourth Annual Southeast NAACP Conference in 1956. This decision not only put Tougaloo under the microscope of the white establishment; it also flagged Rev. Mangram as a target for any white supremacist group in central Mississippi.

In 1960, Reverend Mangram must have had remarkable courage; instead of hiding from the authorities spotlight, he again put himself in at the frontline of the Civil Rights Movement by organizing Tougaloo’s youth branch of the NAACP. These courageous acts by the reverend sent a strong message to hyper-segregated Mississippi and the Tougaloo community. In the words of Joy Ann Williamson, “These individual acts of resistance primed Tougaloo for the role it assumed in the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement” (Williamson 558).

As the Civil Rights Movement advanced into the 1960s, so did the Tougaloo College Social Science Department’s forum program. During the Forum’s formative years in the 1950s, speaker lists generally contained faculty and Civil Rights advocates from the Jackson area, such as the NAACP’s Medgar Evers, Millsaps’s Dean James Ferguson, or Jackson author Eudora Welty. However, as the reputation of Tougaloo’s social advocacy expanded, so did the college’s scope of speakers. By the 1960s, the event brought global social titans including the United States “ambassador to Egypt and the NBC correspondent to the United Nations” (Lowe 874). This practice exposed the practices and social damages of American apartheid in arguably its most brutal stronghold to influential dignitaries outside of Mississippi society; simultaneously, these powerful people gave ideas of freedom, social justice, and equality to the students and staff who attended the forums. Tougaloo operated forums from the early 1950s to the 1980s. They galvanized the intellectual community, spat in the face of Mississippi’s white supremacists, and passed the torch of civil rights to the students who sat in attendance at these forums (Lowe 879).

Spelman and the Rapid Transformation of a Student Body

Spelman College holds the title of America’s oldest and most renowned black liberal arts college for women. The school began in 1881 thanks to Sophia B. Packard and Harriet E. Giles from Salem, Massachusetts. These two Caucasian, New England women founded Spelman in the basement of Atlanta’s Friendship Baptist Church with the support of the Women’s American Baptist Home Mission Society. Packard and Giles envisioned a female institute based on the ideals of the New England liberal-progressive outlook and Protestant ethics (Lefever 1-2).

Over the next seven decades, Spelman abandoned the trade school components of its curriculum and liberal-progressive tendencies, evolving into a highly academic and ultra-conservative institution for women by the mid-1950s. The school prided itself on its Puritan-like character, religious devotion, and academic standing. The administration’s approach to the surrounding segregated city was one of noninvolvement; students and faculty did not patronize anything segregated, but the college did not make any open efforts to confront it. Rather, the school isolated its student body from the brutally segregated environment (Lefever 15-18). In 1957, Spelman College seemed like the last place to find students or faculty willing to participate in social activism. However, the social barriers between Spelman College and the segregated world began to crumble with the initiation of Spelman’s own study abroad program. Beginning in the late 1950s, small groups of students traveled to Europe as Merrill Scholars, spending as long as fourteen months abroad. Overseas, scholars found institutional racism similar to that in America. Unlike in the United States, however, university students often rallied and protested the inequality with which minority groups had to deal. Herschelle Sullivan discovered that in Paris “student demonstrations became something common and natural to me… I guess I [accepted the fact that there is] nothing unusual about students mobilizing around a given cause” (Lefever 19-20). Herchelle Sullivan, Marian Wright, and other Merrill scholars carried ideas of student protest and youth activism back to Spelman in 1959 and 1960. The young women of Spelman College now awaited a movement around which to mobilize.

The student body did not have to wait very long. Beginning in February of 1960, the Greensboro sit-ins began, and students from Spelman College and the other five schools of the Atlanta University Center united and began to prepare for activism through regular meetings and workshops. Unfortunately, the presidents of the six united universities, with the exception of Morehouse College’s Dr. Benjamin Mays, wanted to keep their students out of the political arena. The Council of Presidents of the Atlanta University Center advised the student coalition to forgo any sort of open activism and instead write a manifesto of their grievances about the social system. The students consented rather begrudgingly to the presidents’ request and appointed a small committee that included two Spelman students to write the piece. Spelman students Marian Wright and Roslyn Pope joined their intercollegiate brethren and wrote “An Appeal for Human Rights.” This letter of grievance appeared on March 9, 1960, in the Atlanta Constitution, the Atlanta Journal, and Atlanta Daily Word, thanks to an $1,800 contribution from the president of Atlanta University, Rufus Clement. With the completion of the appeal, students from Spelman College, Morehouse College, Atlanta University, Interdenominational Theological Center, Clark College, and Morris Brown College formed the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights (COAHR) (Lefever 25-33).

COAHR began planning rapidly. Less than one week after the publication of “An Appeal for Human Rights,” the students held their first sit-ins at ten lunch counters that were located in government buildings. Spelman faculty member Howard Zinn planned the sit-in with COAHR members in his living room and sent fourteen Spelman girls to the first wave of sit-ins, all of whom the police arrested. Despite the Atlanta government’s swift defeat of the sit-ins, Spelman’s involvement level attracted some attention. On April 10, 1960, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered a speech to Spelman College. This speech invigorated the student body and marked the beginning of King’s relationship with the COAHR community (Lefever 33-41).

Between April and August of 1960, COAHR expanded its activities to include lunch counter sit-ins, store pickets, and white church sit-ins, but Spelman’s student involvement in 1960 peaked on October 19, 1960. On that day, Dr. King met twenty-one Spelman girls and thirty other COAHR affiliates to go to upscale, segregated restaurants. The King and the coalition members all faced arrest for breaking segregation laws (Lefever 45-63).

Alarmed at the arrest of so many of his students, Spelman President Albert Manley delivered a speech two days after the mass arrest. In his speech, Manley emphasizes that those at Spelman should focus on academics and stay away from protests and demonstrations (Lefever 71). This speech set the tone for the Spelman administration’s approach to student activism. Manley established policies “that attempted to stifle student involvement” (Wade). Later, President Manley fired COAHR’s faculty mentor, Howard Zinn (Wade).

Despite opposition from administrators, Spelman students grew more politically active. In 1961, the girls started traveling to other states to demonstrate and found support from the SNCC. In 1962, Spelman girls joined the Freedom Riders and protested at Grady Hospital. Meanwhile, the sit-ins continued through 1964 (Lefever 107-183).

Spelman’s age of activity lasted from 1960 through 1967. During this time, a passionate core of students consisting of at most five percent of the student body led the student movement in Atlanta. These few women held leadership positions in the COAHR community alongside male counterparts and sacrificed dearly for their ideals of social justice (Lefever 253-56). Today, the academic and campus dialogue of Spelman reflect its legacy of Civil Rights activity. However, current policies and proposals, such as the anti-protest policy, betray that legacy (Wade). As I show below, other HBCUs have shared Spelman’s post-1960s views on protest.

Hampton University and the Redefining of Historically Black Colleges and Universities

In 1861, the Union Major General Benjamin Butler took control of Hampton, Virginia, and made its area a refuge for runaway slaves. In the same year, Mary Peake came to “The Grand Contraband Camp” where the former slaves dwelt and started teaching. Using the shade of a simple oak tree as a facility, her first class commenced on September 17, 1861, and marked the birth of Hampton. For the remainder of the nineteenth century, Hampton grew into a leading trade and teacher school for African Americans and drew students from all across the country, including Booker T. Washington (hamptonu.edu). Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, as it was originally called, incorporated manual labor into its teacher-training program and vocational curriculum, becoming the model that many early HBCUs emulated (Anderson 34).

Like many other private black colleges and universities, Hampton gradually abandoned most of characteristics of the “Hampton Model” over the course of the twentieth century. However, it clung to its mission of “preparing graduates for a segregated world” (Page). By the early 1970s, what was called then Hampton Institute had evolved into a leading HBCU, thanks to its orientation of preparation and successful graduates. Despite its gains, Hampton faced two key issues in the 1970s: a discontent student body and a post-Civil Rights Movement identity crisis.

During February of 1960, Hampton students launched the sit-in movement in Virginia to protest the unequal service given by businesses. In addition to providing student activists, Hampton attracted several leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, including Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Rosa Parks became a hostess at the campus hotel (hamptonu.edu). After about 1968, student activism lost its welcome at Hampton, but the passion for change and social justice did not fade. The Hampton Institute of the 1970s still faced its historic resource limitations, which limited the quality and variety of course offerings. At the same time, Hampton’s level of Civil Rights involvement showed sharp decline form the previous decade, despite the student body’s maintained commitment to social justice. As a result, the student body experienced terrible frustration with the institute’s academic and social policies, climaxing with arson in 1972. Meanwhile, newly desegregated predominantly white institutions (PWIs) began recruiting the brightest of the African American community to their better-funded and better-staffed campuses. For the first time, Hampton and other HBCUs had to compete with PWI for their student bodies. This phenomenon resulted in a fear for the long-term survival of Hampton Institute and other members of the HBCU network (Page).

Caught in a web of rapid change, the Hampton administration instituted an overhaul of nearly every facet of the university. Academically, Hampton presidents Roy Hudson and William Harvey expanded the school’s scholarly programs through university partnerships, created a core curriculum, formed an M.B.A. program, built centers for high-tech research, and advanced the continuing education program (hamptonu.edu). The presidents’ aggressive advancement campaigns nearly doubled the student population in ten years and turned Hampton Institute into Hampton University by 1984 (Page).

Socially, Hampton completely banned all student protests and tried to promote a sort of pan-HBCU enthusiasm. The administrations of the 1970s pushed for heightened emphasis on athletics to create friendly rivalries between HBCUs and provide a different outlet for the students to be visible. At this time, Hampton still endured very strained relations with most PWIs, so the school looked to other HBCUs for academic partnerships. Sports also gave the students a means of visibility outside of political protests and demonstrations (Page).

In addition to athletics, Hampton, as well as most other HBCUs, strengthened the administrative and student focus on community service. Hampton wanted to “redefine what it meant to be a responsible graduate of an HBCU” (Page). During the 1960s, Civil Rights figures, such Dr. King, and student activists, such as Herschelle Sullivan, served as the prime examples of socially just affiliates of the African American education system. In the 1970s, Hampton Institute rechristened social justice, making it more about giving back to the community than challenging injustice in the social system. This approach fostered politics of respectability rather than rebellion and still satisfied the progressive desires of the Hampton student body (Page).

In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Dr. Roy Hudson and Dr. William Harvey transformed Hampton’s identity from a small, activist black college to a large, research HBCU in just a decade. More importantly, the two men altered the mission of Hampton from preparing African Americans for a completely segregated world to preparing an ever-diversifying student body for an incompletely integrated world. In a sense, however, the institution does what it always has: operate with an orientation of student preparation.

Overall Developments of Historically Black Colleges and Universities

The United States’ 105 colleges and universities that comprise the black higher education system have profoundly impacted social developments over the course of American history. Born in the early 1800s to provide educational opportunities to African Americans along with other oppressed minorities and reborn after the fall of the Confederacy, the black school system rapidly advanced through the support of the Freedman’s Bureau, northern philanthropies, and church support. The trade school model and the liberal arts model emerged as the two forms of black institute; public HBCUs usually emulated trade schools while private HBCUs typically were liberal arts schools. Public HBCUs trained future black professionals under the threatening thumb of the Caucasian power system, but private HBCUs utilized their independence from state funds and jurisdiction to challenge segregation and other forms of white supremacy.

As shown by Tougaloo College, the HBCU system offered some support for the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s at the administrative level. Tougaloo offered its campus to Civil Rights leaders so they could meet and plan activities without having to worry about interference from white supremacists. Also, the college sponsored forums to unite diverse students and faculty in the fight against social inequality.

As shown by Spelman College and its allies in COAHR, the HBCU system offered a core of very passionate and active students to serve on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. These students participated in sit-ins, marches, pickets, workshops, boycotts, Freedom Rides, and petitions. Likewise, Spelman’s core of activists proved very effective in desegregating businesses and absorbing the blows of segregationists’ counteroffensives. Important figures like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. sought alliance with HBCU student activists and participated with them in Civil Rights activities.

As shown by Hampton University, the Civil Rights legislation of the 1950s and 1960s had a profound impact on the identity and mission of historically black colleges and universities. The perpetuation of funding shortages from apartheid days and the steep decline of Hampton’s political involvement created destructive levels of unrest in the students of the 1970s. Additionally, the desegregating of PWIs placed recruiting pressure on HBCUs since the African American community now had access to other institutions. Hampton Institute responded with an explosion of academic opportunity and a shift in social focus, which rapidly transformed the school from a small, activist institution to a premier black research university within a decade. Hampton altered its mission to fit the needs of a world that altered for the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s; yet, Hampton University and the HBCU system at large have maintained their relevance to the modern world by maintaining their core practice: operating with an orientation of student preparation.

Tougaloo College, Spelman College, and Hampton University have unique niches in the higher education system. Each school played an important role for its respective state in the fight for Civil Rights, and all three schools have adapted to the modern sociopolitical landscape. These three HBCUs show that historically black colleges and universities made major contributions to the push for social justice, and that the African American higher education system has had to make some fundamental changes to remain competitive and relevant to modern America. Whether these institutions were responding to the call to social activism or morphing to better accommodate for changes in society, HBCUs did so for the betterment of the people that they serve and the nation in which they reside.

However, Governor Barbour’s previously mentioned consolidation proposition flows from the view that HBCUs have failed to retain their relevance and importance in the modern world. Haley Barbour does not stand alone in his view; even Civil Rights scholars often turn blind eyes to the black higher education system’s historic achievements and recent adaptations. However, Barbour’s line of thought neglects a legacy of outreach to the marginalized that still strongly resonates in all facets of the HBCU system. His proposition also overlooks the radical changes that these institutions have implemented over the past four decades. In fact, the former governor’s plan perpetuates one dozen decades of the public HBCUs’ vulnerability to the whims of state government officials, some of whom will shelve over one hundred years of history for miniscule budget savings. In the end, this system’s important place in America’s social history and recent adaptations to the modern context bear too much weight to be ignored or forgotten.

Works Cited

Allen, Walter. “Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Honoring the Past, Engaging the Present, Touching the Future.” Journal of Negro Education. 76.3 (2007)

Anderson, James D. “Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935.” The Education of Blacks in the South 1860-1935. University of North Carolina Press, 1988. Print.

"HISTORY @ HAMPTON." Hampton University: The Standard of Excellence. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Dec. 2013.

Lefever, Harry G. Undaunted by the Fight: Spelman and the Civil Rights Movement, 1957/1967. Macon, GA: Mercer UP, 2005. Print.

Lowe, Maria. Saige Publications, Inc. “Sowing the Seeds of Discontent.” Journal of Black Studies. Vol. 39.6 Pages 865-887 (2009).

Oslwang, Steven, and Edward Taylor. “Peril or Promise: The Effect of Desegregation Litigation on Historically Black Colleges.” The Western Journal of Black Studies. 23.2 (1999): 73. Expanded Academic ASAP. Web. 23 Sept. 2013.

Page, Hugh. "Interview with Dean Page about Hampton University." By William Billups.

Stewart, Pearl. “Activists Mobilize to Preserve Mississippi HBCUs.” Diverse: Issues of Higher Education. Vol. 26.26 Page 8-10 (2010).

Wade, Bruce. "HBCU and Civil Rights Research." Message to William Billups. 05 Nov. 2013. E-mail.

Williamson, Joy Ann. "This Has Been Quite a Year for Heads Falling": Institutional Autonomy in the Civil Rights Era." History of Education Quarterly 44.4 (2004): 554-76.

Wilson, John S., Jr. “A Multidimensional Challenge for Black Colleges.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. 5th ser. 58 (2011): n. pag. Print.

Discussion Questions

- Billups has conducted different types of research to develop his ideas about Historically Black Colleges and Universities and make an argument about their role in the struggle for civil and human rights. How would you say he uses his library research and interviews to develop a sense of authority in conveying credible, relevant information about the role they played?

- Billups defines a compelling issue in his research that he wants to resolve. Choose a paragraph that stands out for you, one that may be interesting, insightful, or puzzling. Underline specific words, phrases, and ideas in order to decide who you think the audience is for this research. Who does Billups want to influence? What words, phrases, and ideas support your argument?

- Conclusions are often used to summarize key points that writers have already made. But Billups takes this conclusion further by drawing out the implications of his research. Pointing to specific words and phrases, do you think the implications he draws follow logically from this research?