I can still remember the stifling heat in Wujek (Uncle) Henry’s house on an August day, intensified by the lack of air conditioning and the plastic-covered windows. His parents purchased his blue house in the early twentieth century, along with their hundreds of acres of potato farm sprawling miles behind his house on Sound Avenue, stretching to the Long Island Sound. He would affectionately speak in English to my sister and me, watching our blonde heads bob in and out of trees, switching into Polish when he berated my father for attempting to help him up from his chair. He had no wife, no children, but he had weekly visits from us. As he hobbled around his farm with my sister and me, Wujek proudly recounted his history: he would work from sunup to sundown, along with his brothers, and then travel to their brothers-in-laws’ farms down the road to help with the harvest.

When he died, the farm was split among his eldest nieces and nephews. My dad was not anywhere in the will, along with my Babcia (grandmother), because they were the youngest of his descendants. My father and I sat holding our breath, wondering about the greed of the family that had moved off the island so long ago—it was my dad who had taken initiative to visit his Wujek, not these people we had never met. However, Wujek was a clever man, and he had negotiated to preserve his farmland with the county years before his death. His house may have been sold, but his farm, and a part of our family’s legacy, was saved.

The problems facing inheritance of farmland after the death of patriarchs and matriarchs are not unique to my family, and the issue is becoming more prevalent on the East End of Long Island. Part of the issue plaguing the East End is the problem of “depopulation,” meaning the “outward migration of young adults” combined with the “aging of the remaining residents” (Li et al. 135). As property prices increase and descendants move away from the East End, there are more incentives to sell to land developers, leading to population increases and shifts in the local economy and community.

There is a stark contrast between the West and East Ends of Long Island, New York. The West is a gateway to the city, an image of densely populated American suburbia, but the East is a representation of something much older. The East End of Long Island is the remnant of a farming society cultivated by the early twentieth-century influx of Polish migrants to America when Families purchased farms across the street from one another until the streets on the East End, such as Sound Avenue, were filled with Polish residents (Wines). Today, however, the community of Polish farmers is facing destruction because of the abrupt end to generational farming. According to Richard Wines, historiographer for the Hallockville Farm Museum, “Typically, the first generation worked hard and acquired the farm and made a success of the operation. Generally, the next generation also stayed on the farm, with the third generation often moving on to other occupations.” As children chose education and urban life over agriculture, they moved away, resulting in no people to assume the family business. Presently, the growing price of real estate on the island and the younger generation’s adversity to becoming farmers is contributing to a shift resulting in the increased purchase of farmland by developers, which is destroying a way of life that Polish farmers have shared on the East End since the beginning of the twentieth century.

The choice to abandon farming and change occupations can be attributed to the shift in the American economy shown by Biblarz et al. in their article “Social Mobility Across Three Generations.” The researchers found that, since the turn of the century, the United States economy has experienced “structural or forced mobility,” also known as forced changes in the occupational structure due to a shift in the economy away from “agriculture and certain manual/production occupations” (190). Additionally, the Americanization of immigrants in later generations led to the desire to complete higher education and gain corporate jobs. For example, the history of the Trubisze family on the East End, featured at the Hallockville museum, shows that their only son did not take over the family farm but instead, “went from his upbringing on the family farm to a career in the utility industry that led, eventually, to his becoming CEO of Columbia Gas of Virginia” (Wines). Apart from access to higher education and the economic shift, the decline of farming also comes from the excessive costs associated with farming, including economic, social, and labor costs. Farming takes time and dedication, with the need for constant labor, whether it be planting, tending, or picking. The life of a farmer is a simple one; it is not a profession that someone takes up to become extremely wealthy.

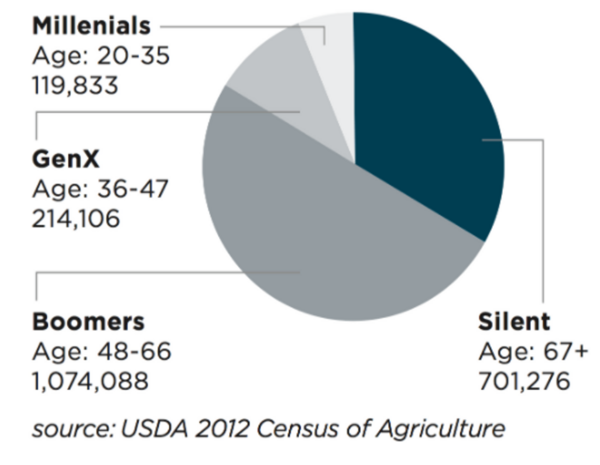

The US Department of agriculture (USDA) found in a census for farmers from 2012 that the amount of the younger generation choosing to farm is significantly less than the older generations. In fact, between 2007 and 2012, the USDA also found that the total number of new farmers had decreased by 20%, meaning a striking fifth of potential farmers were lost to other professions (“Farm Demographics”). According to Figure 1, there are about 119,833 Millennials and 214,106 Gen X that are principal operators of farms, and the largest groups of operators are both the silent generation and boomers that are 701,276 and 1,074,088 people, respectively; therefore, Millennials and Gen X—the younger generation—make up approximately 15.25% of the total farmers in the United States (“Farm Demographics”). I am not blaming the younger generation for abandoning the profession of farmer; rather, I am appealing to their apathy towards their agricultural roots, and imploring them to take a more active role in protecting their heritage by preserving the Polish farming community on the East End. I propose that a solution to the decline in generational farming is not to have more farmers, but to combat the disinterest of the younger generation by igniting a socioemotional connection, rather than economic connection, to their familial land. By exposing the younger generation to farming and their family history through interaction with the land, the younger generation can make more informed decisions about protecting their families’ farms through either the preservation of land or the sale of their land to wineries. In appealing to the younger generations’ emotional connection to the farms that they inherit, the descendants of Polish farmers can work together to preserve the farming community of the East End.

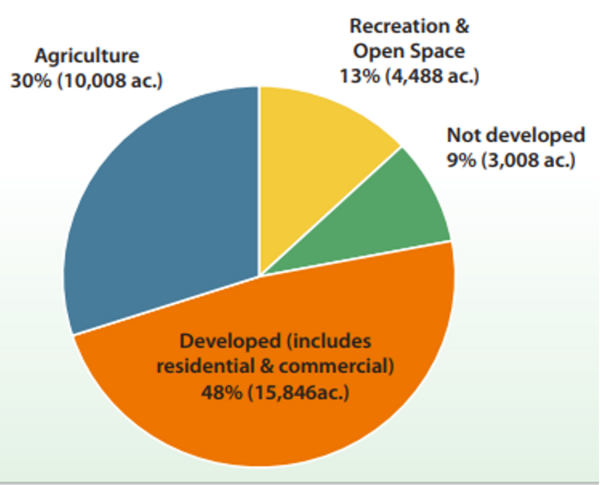

The farming industry on the East End is vital to the economy of the small community. Agriculture, the third largest industry in Southold, a small town on the East End of Long Island, totaled 120 million dollars in 2008 (“Agriculture”). As shown in Figure 2, a chart from the Southold Town comprehensive plan to preserve the community, about 30% of the land in Southold is allocated for agriculture (“Agriculture”). Yet, the amount of land being used for agriculture is decreasing over time. In a report by the New York State Comptroller DiNapoli concerning agriculture on Long Island, “The amount of land devoted to agriculture in Long Island declined from 150,680 acres in 1950 to 37,243 acres in 1992” (DiNapoli). The shift from agriculture to urban development is attributed to the combination of “high land prices” as well as high “inheritance taxes,” and, in the period between 1982 to 2007, “one out of every three acres ever developed in the United States was developed” (Paolisso et al. 12). In regards to the decrease in farmland, Bob Ghosio, Town Councilman of Southold, warns about the implications for the local community and economy: “If, all of a sudden, the farmers went away and we put houses up, there’d be an awful lot of business in Southold that would go in the way of the wind” (Khan). Paolisso et al. echoes the sentiment that, once land is developed, it makes it impossible for rural communities to “preserve their heritage and way of life” which leads to impairments in the community (Paolisso et al 12). To combat the communal harm of development, the Town of Southold has adopted a comprehensive plan detailing the steps that Southold can take to promote agriculture and the local economy that emphasizes the ideas of “tradition” and “preservation.” The mission statement adopted by the town is as follows:

The Town of Southold is a community of extraordinary history and beauty. […] Our citizens cherish Southold’s small-town quality of life and wish to preserve what we currently value while planning for a productive and viable future. Future planning shall be compatible with existing community character while supporting and addressing the challenges of continued land preservation, maintaining a vibrant local economy, creating efficient transportation, promoting a diverse housing stock, expanding recreational opportunities and protecting natural resources.

Southold town is responding to the shift that their community is experiencing and thus addresses the importance of “preserv[ing]” and “maintaining” “small-town quality of life” in their mission statement. However, the plan of the town is only an outline of responses to the decline in generational farming and the change in the community. The town can propose solutions but cannot implement the solutions; those are reliant on the younger generation, the owners of the land.

One of the proposed solutions to solve the issue of declining zoning for farms on Long Island and prevent harm to the Polish farming community is preservation. A combination of trusts, donations, and government programs fund preservation, yet families considering preserving their ancestral lands face issues such as the desirability of real estate as well as the cost of land. Problems with preservation include the legal restriction of property rights, application lists that are years long, the purchase of land for less than a “property’s appraised value,” as well as limited funds from the county, grants, and donations (Kurland 249). The main apprehension for farmers to preserve their land is the high economic opportunity cost. By choosing to conserve land, farmers experience financial constraints because they must “donate their land” for a tax benefit or “sell for a price that was much lower than market value,” forfeiting any possible economic gain from generations of their families’ hard work (Paolisso et al. 18). Therefore, farmers are not fairly compensated for the land that they are choosing to preserve, and oftentimes the best economic solution for farmers is to sell their property for its actual value. Thus, land developers are the most profitable possibility for both farmers who want to leave money to their children and inheritors of land who do not want to face the lengthy process of preservation.

Consequently, land developers have bought significant portions of land on the East End of Long Island; one such wealthy developer is Stefan Soloviev. In the article “Four More North Fork Farms Sold to Stefan Soloviev” Tim Gannon, writer for The Suffolk Times, a local Suffolk County newspaper, interviewed Soloviev to evaluate his intentions for the land he had acquired. The land bought by Soloviev was originally set aside to be preserved but was purchased after preservation talks fell through with the property owner. Soloviev, concerned with his public image on Long Island, repeated statements that he had “no plans of developing [the] property right now” (Gannon). Soloviev is different from most developers because he wants to stay in the good graces of the community by stating his intention of continuing to use the land for agricultural production. However, there have been talks that his son plans to build houses on the farmland, contradicting his statements that he was not building housing on the farmland. Thus, without legal preservation of agricultural zoning for land, the promises of developers are non-substantial.

Although it appears that bottlenecks in the preservation process as well as economic opportunity costs hinder the goal of preserving family farms and helping the community surrounding them, another factor is at stake in the younger generations’ feelings in their decisions regarding their farms: socioemotional wealth theory. Socioemotional wealth theory is defined as the “sacrifice of economic” self-interest for socioemotional gains and has been found to be one of the most convincing factors in helping boost declining rural communities (Kurland and McCaffrey 244). In “Community Socioemotional Wealth: Preservation, Succession, and Farming in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania,” Kurland and McCaffrey’s article argue that, “family firms are more embedded in their local communities, they are more likely to protect and preserve the social and natural environment, at the firm’s expense in that community” (246). The descendants of the Polish farmers on the East End are similar to the idea of “family firms” because they have a stake in the local community—their farm is like a firm—and the younger generation has shown their contribution to the local community over the years even after abandoning the profession of farmer.

In the 1960s, Ruth Foley, daughter of a farming family and Sag Harbor community member, won the title of Potato Queen. Ironically, she used the $1,000 prize to fund her nursing degrees, and thus her participation in the community event enabled her to abandon agriculture (“When Potatoes were King, She was Queen”). Foley is an example of a descendant of Polish potato farmers that decided to switch careers; however, she decided to build a house on her family’s farm and thus continued to be a part of the farming community without participating in the agriculture industry. Foley, a member of the community for many years, has come to appreciate the preserved farmland around her while also reflecting on the change in her town. For example, when the construction next to her land ended in 2015, Ms. Foley was shocked that she would have next-door neighbors for the first time (“When Potatoes were King, She was Queen”). Foley’s experience staying in the town demonstrates the interaction between inheritors and change in the community, and the combination of both preservation and construction around her property signals the different choices that farmers have taken as agriculture has declined.

Although it may seem that most farmers and inheritors would choose the more economical option, Kurland and McCaffrey found that among farmers in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, “the decision to preserve land for limited financial return was motivated by emotional attachments to a family tradition of farming and to their land” (255)—meaning that the connection of farmers to the land that their families’ have farmed for generations has heightened their emotional attachment to the farm and reflects the significance of socioemotional wealth theory. Even though “the market value of the land was much greater if sold for nonagricultural development,” the farmers of Lancaster County chose to preserve rather than sell their land (Kurland and McCaffrey 255). The connection of Lancaster County farmers to their land and the choice of Ms. Foley to stay on her family’s farm reflect that exposure to a community can strengthen the socioemotional connection to land. Therefore, to form an emotional connection to land, families must take an active role in exposing the younger generation to their farming roots and talking about the choice of preservation, which may develop an understanding of the joint significance of the land to the community and their family history.

The Peconic Land Trust, one of most prominent land trusts on Long Island, is a resource for the younger generation because it focuses on preserving farmland due to economic and ecological concerns. Economically, the East End of Long Island has been a focus of preservation because as real estate has become more expensive, and therefore trusts are needed for inheritors who cannot afford to preserve. In fact, Suffolk County, New York was the first county that moved to preserve farms in the United States, which signals the importance of farmland in the local East End community and to the county economy (Kurland and McCaffrey 248). The Peconic Land Trust raises money and brokers deals to fund preservation projects focused on gaining land rights from the descendants of East End farmers. However, as previously mentioned, preservation can be costly for both the trust and the seller, and thus economic constraints may prevent the preservation process from proceeding. For example, a 100-acre project in Riverhead required “six lines of credit from supporters of conservation to raise the $11.5 million for the purchase and $500,000 for carrying costs” (“Peconic Land Trust”). Although the amount of money for the project was a considerable sum, it was not the full value of the land, and “the trust purchased the property from Walo, LLC at a bargain sale price” (“Peconic Land Trust”). Andreas Weisz—granddaughter of the patriarch of her family, Stanley Weisz, who bought the 100-acre property—commented to the trust that, “My grandfather always wanted to see the land preserved, what we called the duck farm. We see this as his legacy, his pride and joy” (“Peconic Land Trust”). Should Andreas Weisz and her family, owners of the property, have wished to take the developers deal over conservation, they would have had a larger payout, but they decided to preserve their land instead. Their dedication to protect their family’s land is evident because originally a favorable offer was made to the Weisz family from a developer, but they “[held] off on signing the contract to see if a conservation outcome for the land could be achieved” (“Peconic Land Trust”). The socioemotional connection of the descendants of the original owner, Stanley Weisz, led them to forgo the better economic opportunity of development for the preservation of the land. The Weisz family is unlike Ms. Foley because they are an example of descendants with no stake in the current Polish community. Yet, the Weisz family still requested help from The Peconic Land Trust to preserve the land and their family history. The aid of trusts and other fundraising organizations can be a valuable resource for the younger generation who wish to prevent development and save their family’s land.

However, if farmland owners are opposed to preserving their land for less than the market value and require an economic payout, there is the possibility of turning to the growing Long Island wine industry. Wineries can be a more profitable option rather than preservation and can also offer certain benefits to the agricultural community including “potential economic alternatives” to non-agriculture-based jobs, “engagement with local communities,” and a “growing industry” that revolves around grape-based agriculture (Alonso and Northcote 143-144). When the first winery opened on Long Island in the 1970s, there was no hope for the newly graduated Harvard couple, the Hargraves (Gryvatz Copquin). They had no experience in farming and assumed the profession after solely completing research about growing grapes (Gryvatz Copquin). However, according to Lucy Hargraves, matriarch of their vineyard, they achieved success after “a neighboring potato farmer named Mike Kaloski, who was known for experimenting with crops, offered to help” (Gryvatz Copquin). Kaloski taught the Hargraves how to farm and saved them from economic failure. The help from the local farming community through Mike Kaloski signals the acceptance of the Hargraves and their wine farm by their neighbors in the Polish farm community. Alonso and Northcote researched the influence of wineries in Western Australia and the Canary Islands and echo the “importance of a healthy interaction between [rural communities and wineries] […] respecting each other’s needs and seeking mutual benefits whenever possible” (Alonso and Northcote 146). The principal factor in farmers embracing vineyards in the local community, like the Hargraves, is to have the vineyards positively impact the economy and community.

Yet, family-run wineries have experienced the same conflicts as farms with the increasing price of rural properties (Alonso and Northcote 145). On the smaller scale—meaning the farming families who want to make a profit in an agricultural business—the establishment of wineries on Long Island seems to be a solution to saving agriculture on Long Island; but on the larger scale, wineries could contribute to the problem of the commercialization of farming. The cost of purchasing and developing wineries on Long Island, as well as the success of the industry, has created a shift from “mainly family-run businesses to ones owned by local and even international investors, like the grape-growing Rivero-Gonzalez family of Mexico, who paid $15 million last year” for a winery on Long Island (Gryvatz Copquin). Therefore, even though wineries are profitable, they may be too fruitful for the Island because they attract wealthy investors and large conglomerates. Nonetheless, the influence of wine industries on local agricultural economies are mostly positive because the switch to wineries provides employment in the local community, influences the younger generation to sell their farmland to farmers, and results in the continuation of the agriculturally based economy, even though it is not the same Polish agriculture community.

In 2016 Great Grandma, Wujek Henry’s sister, passed away. My family had to make a decision regarding her land. There were proposals by wealthy developers—fights and tears—but looking back at the decision of Wujek and the arduous work of their ancestors, my Babcia and her sisters decided that the most important course of action was to preserve the land that they had grown up on—even though they did not gain anything economically. Although the agricultural legacy of my Great Great grandparents ended, their land—to the relief of my family—was preserved.

In the current generational farming crisis, it is clear that those in the younger generation are choosing careers other than agriculture, and the amount of family farms are decreasing. By countering the economic appeal of land developers and appealing to the emotional connection of land inheritors by promoting land preservation through interaction with farmland and the embrace of the wine industry, the farming culture on the East End, along with the family history associated with it, will not disappear. It is important to preserve the heritage and land of the Polish farming community on the East End of Long Island because of the significance of agriculture in the local economy, as well as the socioemotional significance of the land to the descendants of immigrant families. The solution to the generational farming decline is reliant on the decisions of the younger generation, and thus it is up to people like me to remember and embrace the life’s work of our Babcias and Wujeks, because without their toils on the farm and the bonds of their community, we wouldn’t have any of the current opportunities today. It is up to us to take an active role in the Polish community to save their legacy and offer our Dzięki (thanks), because it is the least we can do for everything they did for us.

Works Cited

Alonso, Abel Duarte, and Jeremy Northcote. “Small Winegrowers’ Views on their Relationship with Local Communities,” Journal of Wine Research, vol. 19, 2008, pp.143158, doi: 10.1080/09571260902891035.

Biblarz, Timothy J., Vern L. Bengtson, and Alexander Bucur. “Social Mobility Across Three

Generations.” Journal of Marriage and the Family, vol. 58, no. 1, 1996, pp. 188200, https://doi.org/10.2307/353387.

DiNapoli, Thomas D. Agriculture in Long Island, Report 10-2013. Office of the State Comptroller, Oct. 2012, https://web.osc.state.ny.us/reports/li_ag_rpt_10_2013.pdf

“Farm Demographics: U.S. Farmers by Gender, Age, Race, Ethnicity, and More.” 2012 Census of Agriculture Highlights. United States Department of Agriculture, May 2014, https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Highlights/2014/Farm_Demographics/Highlights_Farm_Demographics.pdf. Accessed 25 March 2022.

Gannon, Tim. “Four More North Fork Farms Sold to Stefan Soloviev.” The Suffolk Times, 20 Dec. 2019, https://suffolktimes.timesreview.com/2019/12/four-north-fork-farms-sold-stefan-soloviev/.

Gryvatz Copquin, Claudia. “The Next Chapter for the Wineries on Long Island’s North Fork.” New York Times, 17 May 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/17/realestate/the-next-chapter-for-the-wineries-on-long-islands-north-fork.html.

Li, Yuheng, Hans Westlund, and Yansui Liu. “Why Some Rural Areas Decline While Some Others Not: An Overview of Rural Evolution in the World.” Journal of Rural Studies, vol. 68, 2019, pp. 135–143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.003.

Khan, Mahreen. “Southold Town Board Adopts Code Change to Allow Agricultural Processing on Farms.” The Suffolk Times, 6 June 2019, https://suffolktimes.timesreview.com/2019/06/southold-town-board-adopts-code-change-to-allow-agricultural-processing-on-farms/.

Kurland, Nancy B., and Sara Jane McCaffrey. “Community Socioemotional Wealth: Preservation, Succession, and Farming in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.” Family Business Review, vol. 33, no. 3, 2020, pp. 244–264, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0894486520910876.

Paolisso, Michael, et al. “A Cultural Model of Farmer Land Conservation.” Human Organization, vol. 72, no. 1, 2013, pp. 12–22, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44148678.

“Peconic Land Trust Acquires 100 Acre Broad Cove in Riverhead.” Peconic Land Trust, 27 Jan. 2022, https://peconiclandtrust.org/press/broad-cove.

“Agriculture: Southold Town Comprehensive Plan.” Town of Southold, New York, June 2020, https://www.southoldtownny.gov/DocumentCenter/View/7275/Southold-Comprehensive-Plan-09_Agriculture.

“When Potatoes Were King, She Was Queen.” The Sag Harbor Express, 6 Aug. 2015.

Wines, Richard. “History of Hallockville.” Hallockville Museum Farm, 23 July 2008, https://hallockville.org/about/history/.