The assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 was a shocking and profound event for people all around the world. It inspired leaders to pursue certain policy and security reforms. Equally significant, it inspired ordinary citizens to take action against such violence. For one young man, such action was taken in an unexpected manner. In the wake of Kennedy’s death, twenty-one-year-old Cuban immigrant Luis Cruz Azaceta decided to pursue a full-time career as an artist in New York City (Uddo). With a past greatly stained by violence, Azaceta has expressed that he found his weapon and his voice through the creation of contemporary art (“Luis Cruz Azaceta—Rafter”). While the tragedy of America’s thirty-fifth President was quickly imprinted in the mainstream consciousness, the plight of Americans who “live on the edge of society” needed a voice to bring it to the forefront. As an immigrant, Azaceta felt that his personal experiences and outside perspective could no longer be kept to himself; he was compelled to become that voice in order to bring awareness to glaring societal issues and overlooked suffering. In doing so, Azaceta would work prolifically and constantly change his artistic style, not allowing himself to be labeled, which made him unique among artists. Azaceta’s artwork, which acted as a compassionate voice for the marginalized, defined the current human condition and confronted the various forms of modern human injustice such as violence, tyranny, and displacement. The various styles Azaceta used to accomplish this objective are simultaneously present in one of his pieces called The Scream, in which he explores the contrasting human capacities for compassion and violence. Examining his early life is critical to interpreting his works of the 1970s and 1980s and understanding why they focus on violence and human suffering.

Luis Cruz Azaceta’s troubled childhood, filled with hardship and violence, played a key role in influencing his art. He was born in 1942 in Havana, Cuba to a mostly stable family. As a child, he never intended to become an artist. Azaceta recalled that in his youth, he wanted to become a pilot in the Cuban Air Force just like his father (“Oral History Interview” 25). However, at a young age he was recognized for having innate talent for drawing. Azaceta attended art class every Friday at his grammar school, during which his teachers told him that he displayed talent in his drawings (Uddo). Azaceta’s life was quite stable until 1952, when mass violence across Cuba broke out. At the time, the Cuban government was controlled by an elected president, Carlos Prio Socarras. His administration was filled with blatant corruption, such as when Prio stole over $90 million in public funds, which was one-fourth of the annual national budget. President Fulgencio Batista, who served as Cuba’s president from 1940–1944, led a military coup which was backed by the United States in 1952. However, Batista’s newfound military dictatorship was immediately placed under siege in 1953. A revolutionary group, led by Fidel Castro, would spark a bloody conflict known as the Cuban Revolution that would last until 1959 (“Cuban Revolution”). Azaceta was only ten when the violence began, and it soon became a regular part of his childhood experience. He witnessed bombings at stores and cinemas. There were frequent shootouts across Havana, and public torturing of citizens by the Batista secret police (“Bio”). Throughout this difficult period, Azaceta’s family was optimistic that once Castro took power, he would end the violence and restore life to what it once was. However, this hope quickly dissipated once Castro ascended to power in 1959.

The cycle of violence and hardship endured by Luis Cruz Azaceta continued through his early adulthood, and eventually led him to channel his energies and vision through art. At eighteen, he was suddenly faced with conscription into Castro’s army. Moreover, the violence persisted as the new government began carrying out mass executions. These were the main factors in his parents’ decision to have him leave Cuba (Sutton). Azaceta was sent to New York City in 1960 to live with family members, which initially was a time of great anxiety for him. He experienced tremendous “psychological fear” whenever he was in public, such as when he would go to the public park, in which the trauma of his violent childhood would torment him (“Bio”). The pain of leaving his parents and being “exiled” to a foreign country with a completely different culture weighed heavily on him. During Azaceta’s first three years in New York City, he was filled with a sense of isolation and felt an absence of clear purpose and identity. He began to draw again as a personal coping mechanism to grapple with his traumatic experiences, and to hopefully find greater clarity in his new environment (Sumrall). Over time, he came to understand that his own diasporic experience was similar to that of other immigrants in New York City, and that they shared similar suffering. Azaceta discovered that his talent in the visual arts could be used to examine and confront the human condition of New York from a marginalized perspective. Determined to pursue a career in art, he decided to further refine his skills at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan from which he graduated in 1969.

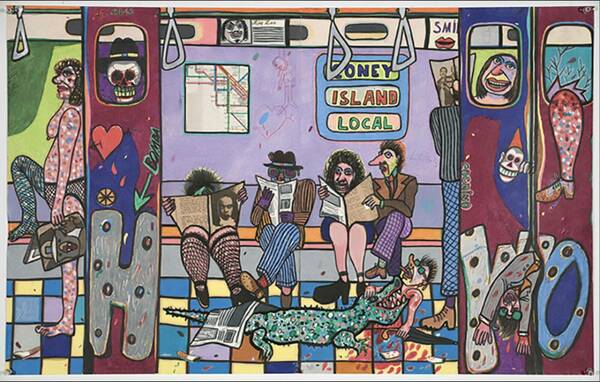

At the dawn of Azaceta’s professional career, he adopted the style of “apocalyptic pop” as a graphic means of depicting the human condition of marginalized segments of society. As with most artists, the young Azaceta was faced with establishing himself as an artist in terms of what art style he wanted to use, what medium to create his art with, and what subject matter to focus on. Following college, he mostly used pen and Prismacolor pencil on paper as his medium and focused on presenting close examinations of his immediate surroundings and the city of New York as a whole. His style was mainly expressionistic, but he occasionally dabbled in abstraction, which was an early indication of his affinity for constant change and flexibility as an artist. He would use blatant absurdities and extreme exaggerations within a recognizably metropolitan backdrop in order to convey his thoughts and discoveries on the current human condition. Such extremities often manifested in the form of nude figures, gore, bodily distortions, and unsettling facial expressions. Azaceta would use wide palettes of vibrant, clashing colors in order to “pop out” individual components from his otherwise cramped compositions (“Oral History” 21–26). In his 1975 expressionist drawing “Coney Island Local” (fig. 1), Azaceta gives the viewer his vision of a New York subway car. A woman who is almost entirely nude can be seen in the far left of the car, while a man is getting devoured by an alligator or a crocodile on the floor in the center of the car. All the other passengers are completely absorbed in their newspapers, oblivious to the bright-red blood getting splashed across the car and pooling towards their feet, and to a woman who is naked in public transit. Although Azaceta is not literally conveying his examination of New York through his expressionist visuals, he is clearly implying the general apathy of New Yorkers towards the glaring problems of prostitution and deadly violence in the city. It was this common theme of a vibrant, cartoon-like depiction of a city in the state of a dark, gory apocalypse that birthed the name, “apocalyptic pop,” which became Azaceta’s defining artistic style.

“Coney Island Local” would become one of the many pieces in Azaceta’s pivotal Subway Series; this series would be one of the first of many to come, but its significance lies in the fact that it earned him his first exhibition. As evidence of his talent, the first art gallery he reached out to was impressed enough to offer him a show. After the opening of the exhibition in May of 1975, he gained substantial respect and attention as an artist, despite only selling one painting. He developed a reputation for being prolific with his artwork, having made around forty-five pieces for the Subway Series alone. He eventually attracted the attention of art critics with the New York Times, who were the first to refer to his style as “apocalyptic pop.” Although Azaceta recalled their criticism as being “cruel,” the unique designation for his work was certainly fitting for his tendency to combine pop with expressionism (“Oral History Interview” 22).

Continuing to organize his work into series, Azaceta finally garnered mainstream critical acclaim for his series on the AIDS Epidemic, which also reflected his desire to explore the human capacity for suffering and compassion (“Luis Cruz Azaceta— Biography”). During the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic became a central concern across the United States, and specifically in major cities such as New York where Azaceta resided. Little was known about this mysterious new disease, which caused mass hysteria and conspiracy theories. A common misperception about HIV/AIDS was that it transmits only through homosexuals. This notion had no scientific backing. Rather, it was because the majority of positive tests at that time were among gay men. The sentiment of the disease being a “gay plague” acted as a major setback for the gay community, which was still struggling for legal and social acceptability. Amid this crisis, Azaceta confronted the growing anti-gay attitude in his city by calling for compassion through his AIDS series. He continued to use gruesome and exaggerated imagery through his “apocalyptic pop” style, but adopted a different medium, acrylic on canvas, instead of Prismacolor pencils on paper. Many pieces show distorted, ghostly figures with gaping mouths, screaming in agony or crying out for help. Clocks can usually be seen to represent the fact that many of the HIV/AIDS victims were counting their days, because they didn’t know when they would be taken by this novel virus with virtually no research or history. Azaceta’s goal was to present his take on the suffering of these marginalized victims in order to generate compassion from the viewers. This is reflected in his artistic statement: “The vehicle for compassion is the aesthetic that draws one into looking closely at what are, perhaps, sometimes horrific subjects and embracing them” (“Artist Statement”). This series on the AIDS epidemic proved to be quite successful and is one of his most notable series to this date. The number of solo exhibitions he had rose significantly and he became increasingly tied with the “apocalyptic pop” style, which was predominantly present in his AIDS series (“Luis Cruz Azaceta—Biography”). However, Azaceta felt the need to move on in order to stay flexible as an artist.

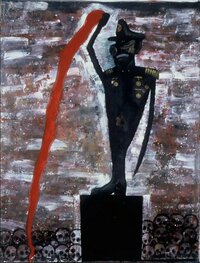

Azaceta still used his art as a voice for “those who live on the edge of society” with his series on dictatorship and displacement, but with a new dominant artistic style. One of Azaceta’s greatest strengths as an artist is his desire to change. He did not want to be solely known for a certain style of art, which is why he quickly moved on from “apocalyptic pop.” Another reason he moved on was his separation from his first wife in 1977, which influenced his adoption of a darker art style (“Oral History” 28). Even while he was working on the AIDS series, he began painting with a dreary tone that greatly differed from his usual popping, comedic style. He continued to use gore and other unsettling imagery, but with more bland, somber colors. Instead of his pieces being crowded with detail, he would create uneventful backgrounds with the only focus being on one or two central figures. As a result of these modifications, this new style took on a more ominous, serious mood. Viewers who once found humor in his cartoonish, absurd compositions now experienced a gut reaction filled with disgust, disturbance, and horror. He used this style to boldly confront the injustices of tyranny and displacement, which Azaceta had personally experienced. This theme manifested in his series on dictators and their victims. “The Dictator” (fig. 2) and a plethora of other pieces in the series are centered around a pig in military attire, which is a reference to Animal Farm. In this 1945 novel by George Orwell, the pigs establish a

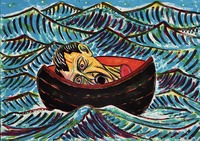

dictatorship and begin dressing like humans, asserting total domination over the other sentient animals. Other pieces were centered around the victims of such a dictatorship and their resulting displacement. These mainly draw focus towards tiny rowboats, which are surrounded by a vast, dark body of water. The people in the raft are gaunt and usually crying out with gaping mouths. In “The Crossing” (fig. 3), there is only a severed head within the boat, signifying the painful reality that many Cubans did not survive the voyage. This embodies the insufferable human condition for Azaceta and other Cuban-Americans who perilously fled from their homes by sea to escape tyranny—though unsurprisingly, Azaceta would soon move on again in the direction of printmaking.

In line with his propensity for change, Azaceta made a lithograph print called “The Scream” (fig. 4) which can be viewed as an amalgam of all his previous compositions in terms of artistic style and subject matter. From the late 1980s till the early 1990s, Azaceta briefly delved into the art of printmaking, specifically in the form of lithographs and silkscreens. “The Scream” is a color lithograph print, which involves using specific technical skills throughout a painstakingly difficult process. Upon close inspection of this 1987 piece, viewers can see the granular texture of the stones which were used to transfer the image onto paper. This makes “The Scream” unique from his previous works, but similarities can be seen throughout the lithograph. “The Scream” uses aspects of Azaceta’s “apocalyptic pop” style and his ominous, darker style to explore two contrasting components of the human condition: compassion and violence.

The composition of “The Scream” is very reminiscent of Azaceta’s previous works, ranging across multiple series, with respect to both artistic style and subject matter. This lithograph is focused on one central figure, which is a grotesque head severed in half. The head appears to be ripped off the body, with its mouth wide open as if it is crying in agony. Such components are also present in Azaceta’s series on displacement and dictatorship, which portray central figures in a similarly grotesque manner. However, the color scheme of “The Scream” is more indicative of Azaceta’s “apocalyptic pop” style due to its expansive, vibrant palette. Impressively, the composition is not crowded like many pieces in the AIDS series are, but he still manages to add the same level of detail to one central figure which is also characteristic of the pop style. This profound attention to detail is possible by homing in on each individual element of the composition to establish multiple meanings within the one central figure.

One of Azaceta’s main objectives in his work is to draw the viewer’s attention towards glaring societal issues and injustices. He would accomplish this through gory exaggerations and blatant distortions of reality that immediately catch the eyes of viewers. When looking at “The Scream,” the immediate emphasis is on the four red and white horns jutting out from the severed half of a human head. Dashed red ovals along a white background inside the horns are pointed towards the tip, indicating organic activity within the horns themselves. Vibrant yellow rings, the same color as the rest of the head, surround the base of each horn where they attach to the head. Using yellow around the horns instead of sticking with the blood red of the cauterized half of the head is important since it clearly defines the horns as a human element. This, combined with the red cell movement, establishes the horns as a human bodily component, freshly sprouting out from the yellow flesh. Azaceta also uses lines in different colors and types in order to show the outward movement of the horns and the rest of the head. Curved, light purple lines provide a contrasting layer in between the subject matter and the dark purple background for the entire piece. These curved lines surround the horns and point towards the edge of the piece, revealing movement in the horns as they jut out from the half-head. In addition, a straight, dark blue line hangs from the bottom of one of the horns in the form of a liquid droplet which further develops the horns as a human body part in movement. Azaceta uses this gory imagery to depict the pervasive violence of both his early and contemporary environment. He purposefully gives a plethora of human-like details to the monstrous horns in order to convey that all of humanity is capable of committing egregious acts of violence based on our innate primal instincts. The creation of a sense of movement was done to bring urgency towards the growing threat of violence and its increasing impact on the modern human condition.

In “The Scream,” Azaceta explores the need for compassion also through the development of religious symbolism. He uses Christian iconography, not to send an explicit religious message, but rather as a metaphorical conduit for defining the current “moral pulse” of the country (“Bio”). To start, the dark purple background of the piece can be attributed to the concept of purgatory because blue and red, colors often associated with heaven and hell respectively, combine to form purple. Azaceta believes American society is in a purgatorial state due to the growing prevalence of violence and a waning sense of compassion for those who are marginalized and who suffer from such violence. While purgatory is a place of limbo between heaven and hell, one can still ascend into heaven given time. Therefore, Azaceta uses purgatory to depict the concept that society has a chance to alter its current course and redeem itself. The blood dripping down from the hair on a severed human’s head is reminiscent of Jesus Christ wearing the Crown of Thorns. Compassion was one of the most valued virtues for Jesus, and he truly embodied it through his actions as described in the New Testament. While donning the Crown of Thorns, Jesus suffered immensely at his crucifixion. Jesus’s slow and painful death represents the inevitable fate of compassion, which is already withering away from the current human condition. In juxtaposition to this imagery are the sprouting horns, which are symbolic of Satan. The established outward movement of the horns indicates that the power of Satan is metastasizing. On the other hand, Jesus is symbolically shown in his most weakened state. Such visual analysis of “The Scream” may seem far-fetched. However, Azaceta recalled using similar religious references in a couple of large paintings he worked on from 1973 to 1974 (“Oral History Interview” 19). Azaceta’s examination of the current culture, in which he perceives a rise of mass violence with a simultaneous decline in compassion, is visually well-established through his incorporation of religious symbolism.

Further analysis of the subtle details within “The Scream” elucidates Azaceta’s urgency to confront violence. Profound signs of suffering can be found on the severed, compassionate face. The person’s mouth is agape and presumably letting out a scream, hence the title of the piece. Azaceta purposefully drew the cheek muscle contracting in towards the nose, which is a small yet profound detail indicating a painful scream. A blue tear streak, similar to the blue line under the horn, is found running down the middle of the person’s eye. The eye also has a red hue, further indicating the person has been crying out of suffering. Such suffering can be attributed to the rise of violence, which Azaceta further conveys by enveloping the person in violent imagery. It is as though the qualities of the demonic, violent half of the head are seeping into the heavenly, compassionate half. The vibrant yellow, possibly signifying a holy aura, and which makes up the remaining flesh, is being engulfed by red streaks of blood. Hair that starts from the cauterized half can be seen carrying over onto the other half. The light purple dashes following the direction of the hair brings outward movement to the object, which shows growth of the hair. Such odd placement for body hair suggests a primal, bestial quality. The jagged and subtly bloodstained teeth are additional primal attributes that indicate a violent nature. Within such detail, Azaceta shows the viewer that violence is encroaching upon the human condition from all fronts. “The Scream” visually depicts Azaceta’s tremendous urgency towards confronting the degradation of the current human condition, in which mass violence is taking precedence over the virtue of compassion.

Through his dynamic artwork, which was heavily influenced by his early experiences with violence and injustice, Azaceta strives to infuse his viewers with both a visceral awareness of the deterioration and ignominy of the human condition and compassion for human suffering. Through “The Scream,” a particularly unique piece which incorporates his varied artistic styles, Azaceta illuminates the human potential for compassion and redemption, and for violence and cruelty. With deliberate purpose inspired by his past, Azaceta uses “The Scream” and his other works as a “vehicle to convey something about the human condition” (“Oral History Interview” 10). However, Azaceta did not always believe in art’s ability to communicate truths about the human condition. As a youth, although his artistic talent was recognized, he never considered art as a profession, since he felt that art for art’s sake or for entertainment was not worth his time. When he moved to New York City as a young adult and felt a sense of isolation and absence of purpose, he used art as a tool to cope with his anxiety. Inadvertently, Azaceta discovered that art has the potential to convey profound meaning. The meaning he illustrated through his art was shaped by the torturing, oppression, and violence he witnessed as a boy in Cuba, which left an indelible imprint on his life and his work. Through his art, Azaceta created a visual lens through which the viewer can see his thoughts, experiences, and perspective in order to communicate certain truths about the state of society. In addition to expressing profound truths, Azaceta also strived to avoid stagnation in his artistic style. Early in his career, he used vibrant colors and grotesque imagery to draw attention to the injustices he witnessed in his current and past environment. In “The Scream,” Azaceta combined his two dominant artistic styles from the first couple decades of his career. Through this visually stunning blend, he intricately defined the current human condition in America through the contrasting human capacities for violence and compassion. While historical events such as Kennedy’s assassination are readily absorbed into the mainstream consciousness, ordinary victims of tyranny, displacement, and violence require the passion, concern, and dynamic creativity of an artist such as Luis Cruz Azaceta, who himself had been traumatized by violence and cruelty, to plant their suffering in the foreground of society

Works Cited

Azaceta, Luis Cruz. “Artist Statement.” Luis Cruz Azaceta, 2018, http://www.luiscruzazaceta-art.com/artist-statment.

--. “Bio.” Luis Cruz Azaceta, 2018, http://www.luiscruzazaceta-art.com/bio.

--. “Coney Island Local,” prismacolor pencil and ink, 1975, Luis Cruz Azaceta—Selected Drawings, 2018, https://luiscruzazaceta-art.com/selected-drawings/.

--. “Oral History Interview with Luis Cruz Azaceta.” Broome Library and CSU Channel Islands, by Denise Lugo, 30 June 1989, http://repository.library.csuci.edu/bitstream/handle/10139/5463/Azaceta_1.pdf?sequence=1.

--. “The Crossing,” lithograph, 1991, Luis Cruz Azaceta—Selected Prints, 2018, http://luiscruzazaceta-art.com/selected-prints.

--. “The Dictator,” acrylic on canvas, 1986, Luis Cruz Azaceta—Selected Early Works, 2018, http://luiscruzazaceta-art.com/selected-early-works.

--. “The Scream,” lithograph, 1987, Luis Cruz Azaceta—Selected Prints, 2018, http://luiscruzazaceta-art.com/selected-prints.

“Cuban Revolution.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuban_Revolution. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

“Luis Cruz Azaceta—Biography.” George Adams Gallery, www.georgeadamsgallery.com/artists/luis-cruz-azaceta. Accessed 30 Apr. 2022.

“Luis Cruz Azaceta—Rafter: Hell Act II.” YouTube, uploaded by Phoenix Art Museum, 9 Apr. 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8in8O7I-5SI.

Sumrall, Bradley. “What a Wonderful World.” Ogden Museum of Southern Art, 2022, http://www.ogdenmuseum.org/exhibition/what-a-wonderful-world/.

Sutton, Benjamin. “A Cuban-American Artist’s Scathing yet Loving Views of His Homeland.” Hyperallergic, 14 Dec. 2016, http://www.hyperallergic.com/343869/a-cuban-american-artists-scathing-yet-loving-views-of-his-homeland/.

Uddo, Kasey. “Q&A with Luis Cruz Azaceta.” Ogden Museum of Southern Art, 12 Jan. 2021, http://www.ogdenmuseum.org/qa-with-luis-cruz-azaceta/.