In June of 2018, my older sister and I tied our shoes in the lowered tile genkan of my grandfather’s countryside home. “It’s just a couple blocks from here,” Emma said, looking up at me. “It’ll be quicker if we take a left where we entered the neighborhood.” I had no memory of my life in Japan. I had only lived there for eleven months before my family moved to America, so there wasn’t much to remember anyway. As we walked out, I slid the fusuma closed. My hands twitched and suddenly felt clammy.

It wasn’t a long walk, but the sun beat on our backs enough for us to break a sweat. Once we arrived at the boxy, unassuming building, Emma toggled with her camera’s settings. Hot air sizzled and crackled as it rose from the boiling blacktop to meet my face. I shielded my eyes from the sun and looked up at the hospital. It was closed for renovations.

“This is it?” I asked. “This is where we were born?” My sister must not have heard. She didn’t answer and kept toggling the settings. The windows were dark, and the automatic sliding doors looked like the ones at Wal-Mart. Considering I hadn’t been back in Japan for 15 years at the time, I was expecting to feel something more, the same something that I felt was missing the entire trip. The most positive emotion I could muster was that the brick pattern looked…neat.

I loved visiting Japan, but I had a sinking feeling that I was only a tourist. Out of the shame of being Japanese in a small Midwestern town, I spent years channeling my white half to fit in with the rest of my class. After feeling nothing upon my visit, a new shame rose in me, the shame of having denounced my culture. To this day, I wrestle with my identity and obligations as a Japanese American. Unfortunately, the question of my place in America is one that Asian Americans across the nation already frequently ask themselves. It is also often answered for us in confusing and contradictory ways. What are the intricacies and inconsistencies of anti-Asian racism that make life in America so conflicting, and how can we reconcile with them?

One prevalent source of shame for Asian Americans is the discrimination we face within our own ethnic groups. Karen Pyke and Tran Dang found in their interviews with second-generation Asian Americans that a spectrum of assimilation exists in Asian communities where both extremes are derogatory. On one end of the spectrum is the “FOB” label (fresh off the boat) which some Asian Americans use to describe their peers who interact strictly within their ethnic circles and lend to Asian stereotypes. On the other end are Asian Americans labeled as “whitewashed” who intentionally distance themselves from ethnic practices to assimilate to white norms (Pyke 156). Asian Americans who characterize the two extremes often feel disdain for each other, using the terms FOB and whitewashed to ridicule ethnic peers (Pyke 154). The rise of intraethnic discrimination led to the development of a bicultural middle that many second-generation Asian Americans try to populate. Unfortunately, navigating a balance between upholding Asian stereotypes and abandoning culture altogether is a challenging, hopeless task that reaps little reward. A participant of Pyke and Dang’s study highlighted this balancing act by saying, “Someone can see me out in the street and call me a FOB because I don’t [measure] up to their standard. And to others I can be whitewashed” (Pyke 157). Many Asian Americans feel shame and frustration trying to find stability in the bicultural middle, just to meet criticisms from coethnic peers of either excessive or insufficient assimilation.

However, this impossible dichotomy would not exist internally in Asian communities without an external pressure to assimilate. In my research, I found Pyke and Dang’s FOB/whitewashed binary to bear a striking resemblance to two other common Asian American labels: the perpetual foreigner and the honorary white. Regardless of birthplace, generation, and English fluency, Asian Americans will inevitably be “othered,” or perpetually treated as foreigners, and must repeatedly prove their American status. Beyond America’s general aversions to Asian culture, Asian Americans historically have not been trusted in the United States, even non-immigrants and U.S. citizens. With the signing of Order 9066 in 1942, the most extreme offense of the perpetual foreigner mentality forced 120,000 innocent Japanese Americans into internment camps, 62% of whom were already U.S. citizens (S. Lee 76). The “honorary white” has come to define an Asian American who through sufficient assimilation has gained enough trust and respect from white people to earn similar treatment (Y. Park 129). The key difference between the two dichotomies is that Pyke and Dang speak from the perspective of conflicted Asian Americans, while the terms perpetual foreigner and honorary white describe white American perceptions of Asian Americans. These terms and their subtly distinct connotations are helpful in clarifying and understanding the differences between Asian American and white American criteria for acceptance.

These two binaries leave conflicted Asian Americans with very few options regarding the pursuit of acceptance in America. Being too ethnic displeases both white Americans and a subset of our Asian American peers, while being too American displeases the other subset. An important distinction between these four terms is that while “honorary white” echoes the same sentiment as the term “whitewashed,” it is often used with a positive connotation. Some proudly labeled “whitewashed” young adults from Pyke and Dang’s interviews said that not being whitewashed would be a social step back, as perceived whiteness improves one’s social status in America (Pyke 166). This is essentially the “honorary white” mentality from the Asian American perspective. For Asian Americans, embracing American-ness becomes synonymous with embracing whiteness. In an analysis of the dangers of superficial high school ethnic celebrations, Professor Gilbert C. Park asked a Korean immigrant high school student if he considered himself American. The student observed that “real” Americans are characterized by white skin and English fluency (G. Park, 457). This feeling that only white people are “real” Americans has historical precedence, as Americanization efforts in the early 20th century sent clear messages about Asian culture by teaching “white middle-class hygiene, manners, diet and food preparation, home management, dress, aesthetic, recreation, and accentless English” (Olneck 384). Since Americanness is so defined by whiteness to this day, the pursuit of acceptance via honorary whiteness necessitates that we distance ourselves from our customs and the perpetual foreigner stereotype as much as possible. The desire to accept one part of ourselves becomes the renunciation of the other. This pressured erasure of our own cultural identities begets intraethnic discrimination and incites identity crises among Asian Americans. We must realize that much of the peer-to-peer criticism and peer discrimination experienced by Asian Americans who struggle to reconcile with their identities only exists because of the external pressure to conform to whiteness.

The struggles of assimilation are so conflicting in part due to confusing expectations of either whiteness or ethnicity, but Asian Americans face additional harmful societal expectations regarding performance, like I did in high school. Our seventh-period teachers had just delivered us our winter break report cards. While my classmates reviewed their grades and checked for their class rank, I promptly shoved mine into my bag. My father taught at the school, so he was able to show me, before anyone else, that my run as valedictorian was over. I truly didn’t mind being demoted to salutatorian. The labels and formalities were superficial and unimportant, especially since I had already been accepted to my ideal university. The new valedictorian and I were good enough friends, so I waved to him on my way out of the building. “Congrats, man! Number one looks good on you!” He laughed and thanked me, but as I was walking away, something stopped me in my tracks. I clearly heard one of his friends say, “Whoa, that’s right! Congrats on finally takin’ down the Asian kid, mister valedictorian. Officially smarter than the Asians. Must feel good.” There’s a certain quota of race jokes that minorities in America will inevitably hear and have to brush off. That’s what they always say--they’re joking! Why should I get so upset over a joke? Maybe it’s because my secondary education prospects were living on prayers, or maybe it’s because he had reduced years of dedication and hard work to a biological quirk, but that comment sticks with me today.

It wasn’t until I began researching that I understood why that particular comment made my blood boil. It wasn’t pride or ungratefulness like I had come to believe, but instead was another contradictory expectation for Asian Americans, a stereotype I had been perpetuating my whole life: the myth of the “model minority.” The term model minority was first used in 1966 by a sociologist named William Petersen to praise Asian Americans for their cultural values that enabled them to “overcome racial barriers and achieve high academic and economic success” in American society (S. Lee 70). While the disproportionate appearances of Asian Americans as decathlon winners and Ivy League alumni may suggest it (Zhou 33), the model minority stereotype is simply not true.

Firstly, the term “Asian American” casts a wide net that unfairly lumps people of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indian, Filipino, Cambodian, Laotian, Hmong, and Pakistani descent with each other. In 2002 almost all Japanese Americans received education past elementary school, but over 60% of Hmong Americans did not (S. Lee 72). Asian Americans as an aggregate do not achieve inordinately high academic success, and of those who do, few actually do so in America. In 2003, over 60% of Indian and Taiwanese immigrants had college degrees before moving to America (S. Lee 73), rendering America’s Asian population more model immigrant than model minority. As far as racial barriers are concerned, while Asian Americans are the most highly paid minority group in the United States (“The Rise of Asian Americans”), a wage gap persists between Asian Americans and white Americans. For the same education, Filipino American men earned only 62% of their white counterparts’ salaries in 2004 (S. Lee 72). Not only does the model minority myth falsely imply Asian Americans have overcome racial barriers to educational and economic opportunities, but it also narrows the definition of success. In 2018, Asian Americans overrepresented high-paying professional occupations such as engineers and doctors, but to this day underrepresent artistic fields such as film (“Composition of the Labor Force”; J. Lee 1). The reality is that equality of opportunity does not exist for Asian Americans in the United States, regardless of our “cultural values” and “work ethic.”

Beyond misrepresenting Asian American “success” in America, the model minority myth ignores the mechanisms that make our lives difficult. While on a personal level the model minority stereotype was used to reduce my accomplishments to features of my biology, widespread acceptance of this stereotype leads to governmental neglect of the needs of Asian American communities. The myth that Asian Americans have “overcome racial barriers” allows the government to ignore the fact that Asian Americans as an aggregate experience a poverty rate higher than the general American population; more specific Asian communities experience poverty rates up to 38% (S. Lee 71). The myth that Asian Americans are excessively academically successful resulted in our exclusion from important legislation such as the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which made no mention of Asian Americans or Pacific Islanders as disadvantaged ethnic groups (S. Lee 73). More recently, a Washington school district excluded Asian Americans as people of color in new policies that aimed to eliminate the opportunity gaps between white students and students of color (Northwest Asian Weekly). The model minority stereotype also only enhances the shame of failure for Asian Americans since the expectation of effortless success is so tied to our identities. It was shocking and nauseating for me to learn that Asian American women are the most at-risk demographic in America for suicide while using mental health services almost the least (S. Lee 75). The model minority myth makes false claims about Asian American success that attach unrealistic standards to our identities and ignore our disadvantages.

However, I found the worst and most shame-inducing aspect of the model minority myth to be its impact on other racial minorities. The model minority stereotype since its inception has been used as an excuse to deny government aid to black, Latinx, and Native Americans. Asian Americans were shown as an example of a race who had without complaint “pulled themselves up by their bootstraps,” which was directly contrasted with other racial minorities to accuse them of inadequacy (S. Lee 70). This false narrative has not only perpetuated injustice for all disadvantaged racial groups in America but has unfairly pitted them against each other. When I speak up about discrimination against Asians in America, I am often met with the argument from both white Americans and other minorities that what I experience, honorary white status and the model minority stereotype, is “good” racism. Good racism does not exist. Despite the socioeconomic struggles of Asian Americans, the comparison of Asian Americans as a “good minority” to other races as “bad minorities” has caused division for decades when it was key for all American racial minorities to stand in solidarity (S. Lee 74). The model minority stereotype has weaponized the perceived success of some Asian Americans to further oppress other racial minorities, which personally, has become another source of guilt.

The model minority stereotype paired with the pressures of white conformity paints an unnerving picture of what acceptance looks like in the United States. Acceptance is not true acceptance. I do not feel a sense of belonging when I am called an “honorary white.” I feel belonging when I am treated like a citizen and not a foreigner in my own country. Life as an Asian American requires navigating a sea of mixed signals, contradictions, and unwinnable scenarios where a commitment to any one identity brings shame for not inhabiting the others.

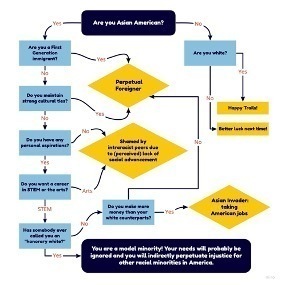

Reconciling with the shame and guilt that accompanies our pursuit of acceptance in America will always be difficult, but it doesn’t have to be an individual struggle. Through researching other Asian Americans’ experiences and the confusing and sometimes hidden mechanisms of anti-Asian discrimination allowed me to gain a grasp of my conflicts and emotions in ways I never have before. It has always been difficult for me to articulate my struggles, but from what I learned in my research I found a way to portray the intricacies and double binds of life as an Asian American in the flowchart below. I believe the only way for Asian Americans to combat our own perceived inadequacies, as well as conventional anti-Asian racism, is to seek the answers, to share our struggles and not allow our conflicted emotions to render us silent. When I visited Japan, I sought the belonging I couldn’t force myself to feel in America, but based on my research experience, maybe all I needed was to understand myself, and for others to understand me. I will ultimately have to answer my questions regarding my identity myself, but by being vocal with ourselves, other Asian Americans, and all Americans regardless of race, we can take the first steps toward breaking down mechanisms of racism, finding true acceptance, and eventually achieving equality. It all starts with opening up and raising our voices. It will not be easy, but it also doesn’t have to be as long as we do it together.

Works Cited

“Composition of the Labor Force.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1 Oct. 2019, www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2018/home.htm.

Lee, Joann. “Asian American Actors in Film, Television, and Theater, An Ethnographic Case Study.” Race, Gender, & Class, vol. 8, no. 4, 2001, pp. 176, http://proxy.library.nd.edu/lo....

***Lee, Stacey & Wong, Nga-Wing & Alvarez, Alvin. "The model minority and perpetual foreigner: Stereotypes of Asian Americans." Psychology Press 26, 69–84 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022...

Olneck, Michael. "Immigrants and Education in the U.S." Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, edited by James A. Banks & Cherry McGee, Jossey-Bass, 2004, pp. 381-404.

Park, Gilbert C. “‘Are We Real Americans?’: Cultural Production of Forever Foreigners at a Diversity Event.” Education and Urban Society, vol. 43, no. 4, July 2011, pp. 451–467, doi:10.1177/0013124510380714.

Park, Yoon Jung. “White, Honorary White, or Non-White: Apartheid Era Constructions of Chinese.” Afro-Hispanic Review, vol. 27, no. 1, 2008, pp. 123–138. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23055227.

Pyke, Karen and Tran Dang. “FOB” and “Whitewashed”: Identity and Internalized Racism Among Second Generation Asian Americans. Qualitative Sociology vol. 26, no. 2, 2003, 147–172, doi:10.1177/0013124510380714.

“The Rise of Asian Americans.” Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project, 30 May 2020, www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/.

von Werder, Joshua. My sister Emma and me visiting the hospital at which we were born. June 2018. JPEG file.

von Werder, Joshua. The Unfortunate Intricacies of Being an Asian American. January 2021. JPEG file.

“WA School District Apologizes for Excluding Asians as POC.” Northwest Asian Weekly, 25 Nov. 2020, nwasianweekly.com/2020/11/wa-school-district-apologizes-for-excluding-asians-as-poc/.

Zhou, Min. “Are Asian Americans Becoming ‘White?’” Contexts, vol. 3, no. 1, Feb. 2004, pp. 29-37, doi: 10.1525/ctx.2004.3.1.29.