It is difficult not to interact with other people through online technology. Our lives and jobs demand participation in e-mail and online communication websites, and for the most part, our experiences with other people online mirror our experiences with them in real life. People tend to be considerate and respectful of the fact that there is a real person at the other screen. However, this is only the behavior that we would expect from our friends and co-workers. It is completely normal. What about non-normal behavior? Are there online equivalents to cults or gangs? Are there online groups that seek nothing more than to harm other individuals? Perhaps. Many people’s reputations and states of mental health have been ruined by false online slander, and some state governments have even seen this as enough of an issue to try to pass legislation increasing online accountability (Gates).

Nevertheless, a more important question to ask is if these online non-normative groups and individuals act in the same way and according to the same psychological principles that their “real life” counterparts do. According to Kimberly Christopherson, a doctor of Experimental Psychology who investigated the related concept of Internet anonymity, experimental psychologists have received mixed results from studies that have tried to identify consistent similarities or differences between interactions that occurred over computers (computer-mediated-communications or CMC) and interactions that occurred in the real world (face-to-face or FtF) (Christopherson). Finding similarities between CMC and FtF communications would allow us to pass laws to regulate CMC that are simply based on our normal FtF laws. If there are distinct differences between CMC and FtF communications, we can avoid restricting Internet freedom and versatility by passing laws that are effective when enforced in the real world, but are misguided when applied to the Internet. The development of unique laws that are well suited to the Internet would avoid the controversy that has plagued current Internet-related legislation (Albanesius). If this issue is left unresolved, the freedom and utility of the Internet could be compromised by erroneous attempts at legislation, and the people whom the legislation is designed to protect could still be at risk. The idea of anonymity and its role in CMC interactions must be taken into account as well, as anonymity has been shown to have both positive and negative effects on interactions on the Internet (Christopherson).

My discussion is framed within the bounds of psychological studies and experiments that range from 1951 to 2013 in publication date. This allows me to tap into the origins of social psychology and recognize how those original theories that were outlined before the creation of the Internet affect modern researchers today. I also use empirical data presented to me from the experiments done that clearly display the results of tests of anonymity and deindividuation in reference to communication. This allows me to make objective comparisons while I also examine subjective opinions published in popular sources such as The Huffington Post that observe what the general public’s reaction to issues related to behavior on the Internet are. Looking at this wide range of sources, I am able to answer the question in a way that directs and inspires further research into the topic.

Anonymity is a crucial aspect of behavioral trends on the Internet due to the separation of the people who are interacting with each other. However, anonymity has been shown to have a significant role in our behavior in real life as well. It is important here to compare the ways that anonymity has been shown to affect people on the Internet and real life and answer the question “How does anonymity relate to non-normative behavior?” Anonymity is frequently associated with non-normative or bad behavior, yet anonymity itself is not inherently bad. By the end of this section, we will have a clearer picture of anonymity as an independent variable from non-normative behavior.

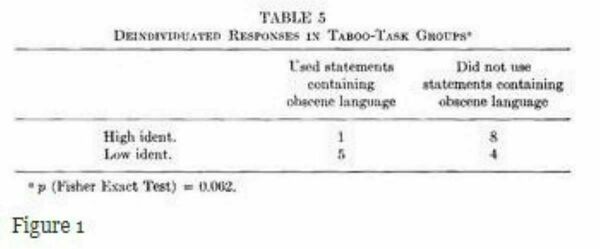

In one of the oldest studies in social psychology, Dr. Jerome Singer and his colleagues at Penn State University performed an experiment concerning the phenomena of “deindividuation” and created empirical data in support of the hypothesis that anonymity increases rates of non-normative behavior. Simply defined by Singer, deindividuation is “a subjective state in which people lose their self-consciousness,” and Singer’s 1965 experiment seeks to place one group of test subjects in a deindividuized state and observe if its behavior is different than another group of test subjects that will remain self-conscious (Singer 356-7). Because of the difficulty in inducing deindividuation, Singer decided to manipulate clothing as the independent variable. He did this because “a person’s choice of clothing seems to be a set of cues which affect his feelings of identifiability without affecting his actual identifiability” (Singer 357). Next, because deindividuation is a subjective mental state, Singer chose to measure levels of deindividuation by how often the subject engaged in a usually undesirable act (Singer 357). The following table displays the number of usually undesirable acts that occurred with both the high-identification or self-conscious group and low-identification or less self-conscious group.

This table displays how there is a statistically significant difference in instances of undesired behavior or “non-normative” behavior when the subjects are harder to identify, and probably experiencing deindividuation (Singer 371). This is strong empirical evidence for the hypothesis that feelings of anonymity can result in increased rates of non-normative behavior. However, this does not mean that non-normative behavior always occurs in the context of anonymity, nor does it mean that feelings of being anonymous always bring about non-normative behavior. The results of this study could be practically applied in order to decrease feelings of anonymity on the Internet without compromising actual anonymity. The application would be the opposite of what Singer did in his study, in which the students were not anonymous but they felt like they were. In order to decrease instances of non-normative behavior on the Internet, all that would be necessary would be to make the Internet user feel like they are not anonymous, even if they may be. Based on the findings of Singer’s study, this should greatly decrease instances of non-normative behavior.

Despite the evidence that anonymity and deindividuation result in higher rates of non-normative behavior, specifically the use of obscene language, it is important to consider that anonymity is not inherently bad and no causal relationship has been shown between the independent variables anonymity and non-normative behavior. Dr. Kimberly Christopherson’s research into this subject has found that anonymity is directly related to the concept of privacy, which is necessary to a person’s mental health (Christopherson 3040). Drawing on experiments performed by Darhl M. Pedersen, Christopherson notes that anonymity “provides three functions as related to privacy,” one of them being catharsis. She defines catharsis as “the unhindered expression of thoughts and feelings to others,” and notes that anonymity would provide an appropriate outlet to express one’s opinion without fear of being judged (Christopherson 3041). This type of anonymous and unrestricted free speech is very prevalent on the Internet, but has been historically sought after for hundreds of years. A good literary example is Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, in which the young girls in a behaviorally strict society seek an anonymous release from the Puritan moral code that has been placed on them. They turn to the slave Tibuta to bewitch the boys that they have crushes on by using magic in the woods. The girls experience signs of deindividuation seeing how they dance and run around naked, both of which would normally be considered undesirable behaviors (Miller 1). The girls in this historical piece of literature are an example of the negative or antisocial behavior that can result from a lack of freedom of expression, and they turn to anonymity and deindividuation as a way to attain that expression and improve their mental health. Some legislatures across the country, such as the New York State legislature, have seen the eradication of anonymity on the Internet as the solution to the problem of non-normative behavior on the Internet. In a bill called the “Internet Protection Act” the state proposed a ban on anonymous comments on New York based websites. The bill was heavily protested and quickly shut down (Gates), but it is a clear example of misguided legislatures attempting to restrict freedom on the Internet in hopes of stopping non-normative behavior. The attempt was misguided in light of the proven positive effects of anonymity, and the assumption that anonymity causes undesired behavior.

All of the examples of deindividuation that we have looked at so far have taken place in small groups. The presence of other people may be a variable that is being ignored in some of these studies, and it is important to recognize the possible influence that peers may have on the process of deindividuation. Social groups exist on the Internet as well as in real life, and social media sites such as Twitter or Facebook focus on communications that take place in larger group settings rather than private conversations between two individuals. Social psychology’s purpose has always been to analyze how people interact with each other, and the extension of this study to the Internet is a natural next step for the field.

If we observe how people act in groups, and reflect on our own personal experience in life, we may assume that individuals belonging to large groups experience higher rates of deindividuation than individuals belonging to smaller groups. This inquiry into the question of group size in relation to individual deindividuation is directly examined in an experiment conducted by the social psychologist Dr. Ed Diener and his colleagues in 1980. Diener’s experiment put subjects in situations where they had to perform silly and potentially embarrassing acts while being observed by expressionless onlookers. The observers would rate the subjects on the intensity with which they performed the embarrassing acts, using the ratings as an estimate for how deindividuated the subject was. After each activity, the subjects filled out a questionnaire that asked them “During the last activity, how self-conscious or embarrassed were you?” and provided a rating system for them to self-asses their self-consciousness (Diener 451). Multiple experiments were performed in which different variables were manipulated. Interestingly, the results of the study provided evidence against the original theory of deindividuation. Diener notes “The lack of predictable behavioral differences between conditions in Experiments 1 and 2 raises questions about the theory of deindividuation. Since self-consciousness did vary between conditions, the theory would predict that disinhibited behavior should also vary, which did not occur” (Diener 457). This lack of correlation between self-consciousness and deindividuation points to a factor other than self-awareness as a cause of deindividuation. If this were true, then just making Internet users self-conscious of their actions would not be enough to stop the development of non-normative behaviors. Another factor must be addressed in the prevention of deindividuation.

A more modern theory of deindividuation, The Social Identity model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE) theory, is a reinterpretation of the original deindividuation theory that seeks to find the factor that was missing from Diener’s experiment. SIDE theory places emphasis on variables within social situations that affect deindividuation (Christopherson 3047), rather than focusing on the individual’s actions. Because social norms are at the center of SIDE theory, researchers have examined how social norms are formed on the Internet before applying SIDE to the Internet. In Professor Michael Rosander’s paper examining the issue of conformity on the Internet, he discusses an experiment in which “the members [of an Internet-based group] acted as part of a unit and favored the in-group even though the membership was built on a basis of no real importance and without a history or planned future” (1588). Rosander notes that the results of this experiment “were similar to what could be expected of ‘real’ groups (f-t-f groups)” (1588). Rosander’s established credibility for the idea that online groups operate similarly to FtF groups in the context of social norms is built on by Christopherson’s research on SIDE theory. Christopherson concludes that “social norms are more likely to be followed when the individual has a high sense of social identity and personal identity is lower” (3048).

Because online groups act in a similar manner to FtF groups, Christopherson’s conclusion can be extended to CMC as well. With CMC, personal identity is lowered by the lack of a physical presence that others can judge from and by the implication of a certain degree of anonymity. This forces Internet users to rely on group norms to define themselves when online, and Rosander argues that the anonymity of the Internet actually increases the strength of these group norms and the behavior that they cause (1588). This further demonstrates that anonymity itself is not the issue that causes non-normative behavior on the Internet, but rather the social norms of some anonymous websites that promote non-normative behavior. By this theory, a completely anonymous website that fosters an environment of positive communication would have a positive effect on its visitors. The existence of communities like this online could provide further evidence against the theory that anonymity is what is wrong with the Internet.

Now that we have shown that group norms are a key factor in the behavior of online individuals, the question remains as to how often people actually conform their beliefs to the group, both online and off. The examination of real-life examples of conformity gives a baseline example of conformity rates to which we can compare online findings. The conformity of people to non-normative behaviors can be seen throughout history with extreme examples in places such as Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia, showing that the phenomenon has a tangible impact on human interactions that is worth investigating in terms of the emerging social construct of the Internet.

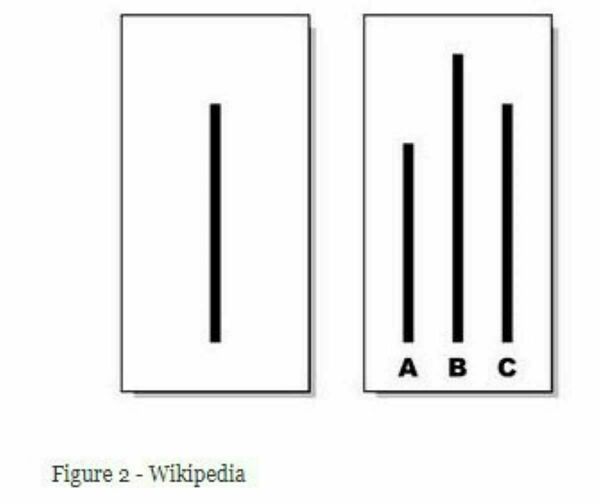

Because people’s tendencies to conform to groups are at the heart of deindividuation on the Internet, it is important to identify the rate of conformity on the Internet and observe how it compares with a normal rate of conformity in real life. Research performed by psychologist Solomon Asch in the 1950s was the first aimed at examining how often people conform their actions to the group norm. Asch gathered groups of students in a room for what he told the subjects was a “visual test.” The subjects were then asked to complete simple visual tasks such as matching the lines in the below figure and announcing their answer out loud.

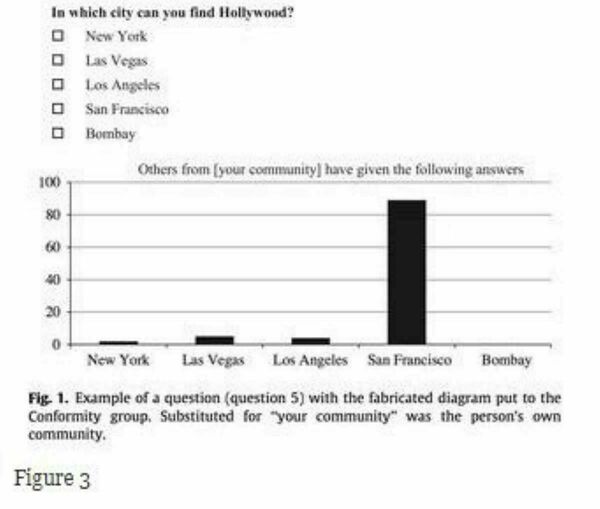

In fact, all of the students were actors except one, and the actors were instructed to deliberately and unanimously choose a line other than the real line as the match for the first line. In the above example, the actors would either all choose A or B. The purpose of the study was to observe whether or not the one real student would say the obviously wrong answer just because everyone around him was saying it. Asch found that the average conformity rate of the real students to obviously wrong answers was 36.8% of the time, and that 75% of the students conformed to the group for at least one answer (Cherry 1; Rosander 1587). These statistics give us a picture of how often we are likely to change our opinions in order to conform to the group in real life, in a simple survey situation. This experiment has been replicated and affirmed many times, and even adapted to fit different contexts such as CMC contexts. When psychologist Michael Rosander and his colleagues replicated Asch’s experiment in a CMC context, they received a different result. Rosander gathered participants from 10 websites with varying demographics and asked them to participate in a quiz-like survey that contained questions on subjects varying from geography to science and questions that tested the user’s logical capabilities. Below each question would be a fabricated graph that claimed to contain the answers of other participants of the quiz. An example is shown below:

(Rosander 1590). The mean conformity rate to the false answer was 13% for this online quiz, less than half of Asch’s test, and 52.6% of subjects conformed once, also lower than Asch’s 75%. The results of the experiment seem to suggest that people feel less pressured to conform to the group norm if there are not physical people around them to pressure them. (Rosander 1592). However, Rosander’s experiment had questions that varied in difficulty, and the experimenters specifically tracked levels of conformity based on the difficulty of the question. The researchers measured question difficulty in two ways: subjective and objective. Objective difficulty was measured by administering the quiz to a control group and observing how many of them got the answers right, and the subjective difficulty was measured by the subjects own feelings as to how difficult a question was. The results of the experiment concluded that average conformity rates greatly increased as both the objective and subjective difficulty increased (Rosander 1592). This is much more relevant to conformity to Internet groups because a new user to an Internet social group or website could be ignorant of the social norms of that website and find it difficult to choose how to act. They would most likely then observe the group for social cues, and mimic the group’s actions due to uncertainty about how they are supposed to act. In those times of uncertainty, Internet users would be especially vulnerable to deindividuation due to group norms.

In the previously described conformity experiments, the subjects only had to decide whether or not to conform to an arbitrary choice in a survey that was not important to them. Information about this type of decision-making would be useless if it did not extend to non-normative behavior or harmful behavior. There have been no studies so far specifically on the frequency of conforming to non-normative behavior on the Internet, but evidence that we have already examined in addition to experiments that address this issue in real life give us a good idea of what may be the case if focused experiments on the subject were to be conducted. The infamous obedience experiment performed by psychologist Stanley Milgram of Yale University in 1963 examined how often the average adult American would conform to the will of an authority figure, despite that will involving hurting another person. Milgram’s subjects were 40 males ranging from 20-50 years old and of varying occupational backgrounds. They were told that they would be participating in a study that would examine the effects of punishment on learning, and they were assigned the role of the “Teacher” who shocked the “Learner” every time the Learner got a question wrong. As the Learner got more questions wrong, the Teacher would administer larger and larger voltages of shocks, with the maximum shock possible at 450 volts. At 375 volts, the fake volt-generating machine read “Danger: Extreme Intensity Shock” and at 435 the machine simply read “XXX.” By the end of the experiment, 26 of the 40 subjects shocked the Learner with to 450 volts of electricity simply because the experimenter told them it was necessary for the experiment, even though the Learner stopped responding after the 300 volt shock (Milgram 2-3,6). This demonstrates how, if we perceive someone to be an authority figure on some subject, we are likely to follow orders from that authority figure to extreme measures. Milgram admits that the setting of the experiment may have added to the sense of authority that the experimenter possessed, as the experiment took place on the campus of Yale University, a highly respected university (Milgram 8), but this does not change the fact that more than half of the subjects obeyed the command to administer a potentially lethal dose of electricity to another human being just because a researcher at a university told them it was important to the experiment. These results astounded Milgram and his contemporaries, but studies involving harming other people have not been done in relation to the Internet, partly due to the ethical controversy that surrounded this experiment.

Research about obedience to authority has been done since Milgram’s experiment, specifically in a CMC context. Rosander’s research references studies in which the social status of members of online groups greatly affect the way in which those members interact with other members. It was found that “low status members more often conformed (changed their public view), agreed (explicit statement) and requested information than high status members” (Rosander 1588). This agrees with the findings of Milgram’s experiment, which showed that people were willing to change their actions to conflict with their opinions when they were a lower status than the person who told them to perform an action. In the context of Milgram’s experiment, the subject has a lower social status than the experimenter, and the subject is typically expected to obey the experimenter, emphasizing both a status differential and an expected social norm. With the presence of two of the most common causes of deindividuation and non-normative behavior, it is not at all surprising that the subjects conformed to what they saw as the group norm. However, further experiments must be performed in which subjects are pressured into making the choice to harm another individual.

All of this information gathered from many existing psychological studies and cultural viewpoints has greatly narrowed our focus as to what we are looking for in order to identify non-normative behavior and the factors that cause it. Because we found that anonymity is not inherently bad, we recognized the need to reduce non-normative behavior without restricting anonymity. This distinction helped prevent the possibility of laws that do not solve the problem of potentially harmful non-normative behavior and yet serve to lessen our online freedom. The identification of social norms as the largest cause of non-normative behavior confirms that the sources of non-normative behavior are an observable entity that can be researched further, and the existing research about how often people conform to harmful or non-normative group norms in real life shows us that there exists a gap in the knowledge about the same behavior online. This points to a two-fold approach toward the issue of regulating potentially harmful non-normative behavior on the Internet. This approach includes further research into the prevalence of obviously harmful non-normative behavior and the regulation of the specific causes of those factors as revealed by research. This is the only possible way to acutely determine the cause of such behavior and address it objectively.

The concepts of anonymity, conformity, obedience, and deindividuation are fully intertwined with each other, and only a full examination of all of these factors in the proper context would allow a comprehensive conclusion about non-normative behavior. This paper scratched the surface of each concept, and by scratching the surface, identified areas that were in need for improvement. While the question addressed in this paper is the important question of what laws need to be passed on the Internet in order to protect us effectively, the question was not necessarily answered so much as it was made progress on. New factors, such as obedience and social status on websites, were discovered as the subject of non-normative behavior was examined more thoroughly, and the research question should be re-shaped in order to specifically address these two factors in more detail when further research is done in the future.

These gaps in knowledge must be filled, for a greater understanding in this field leads to the further development of astounding social and cultural influences on the Internet. The Internet has grown and flourished the way it has because of the lack of restrictions on it, and people have experienced both the overwhelming rewards and crushing defeats this type of free system allows. However, in an age where children’s first online experiences are occurring younger and younger, the responsibility falls on the current Internet-using generations to both protect them from the worst of this free system and preserve it for their unhindered use as adults. If we do not, we may rob the next generation of a beautiful system for the transfer of information that we have only begun to discover the potential of.

Works Cited

Albanesius, Chloe. "Internet Groups Launch Anti-CISPA Protest." PC Magazine. Ziff

Davis Inc., 16 Apr. 2012. Web. 9 Nov. 2013.

Cherry, Kendra. "The Asch Conformity Experiments." About.com Psychology. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2013.

Christopherson, Kimberly M. "The Positive and Negative Implications of Anonymity in Internet Social Interactions: “On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog”."Computers in Human Behavior 23.6 (2007): 3038-056. Web.

Diener, Ed, Rob Lusk, Darlene DeFour, and Robert Flax. "Deindividuation: Effects of

Group Size, Density, Number of Observers, and Group Member Similarity on Self-

consciousness and Disinhibited Behavior." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39.3 (1980): 449-59. EBSCOhost. EBSCO. Web. 4 Nov. 2013.

Gates, Sara. "Anonymous Comment Ban: Internet Protection Act Threatens Online

Anonymity For New York-Based Websites." The Huffington Post. N.p., 24 May 2012. Web. 18 Oct. 2013.

Milgram, Stanley. "Behavioral Study of Obedience." The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67.4 (1963): 371-78. Print.

Rosander, Michael, and Oskar Eriksson. "Conformity on the Internet – The Role of Task Difficulty and Gender Differences." Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012): 1587-595. Science Direct. 21 Apr. 2012. Web. 4 Nov. 2013.

Singer, Jerome E., Claudia A. Brush, and Shirley C. Lublin. "Some Aspects of Deindividuation: Identification and Conformity." Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology 1.4 (1965): 356-78. Science Direct. Web. 13 Oct. 2013.

Discussion Questions

- Creedon concludes that "anonymity is not inherently bad" and argues against creating laws that restrict online activities. Do you think that Creedon gives sufficient attention to the many abuses--and even violent crimes--that have been associated with online activities in the past few years? Based on what we see of his research, is it ethical for Creedon to argue in favor of greater anonymity and personal freedom on the Internet? Why or why not?

- Research papers appeal to specific audiences. Who do you imagine Creedon's ideal readers would be? One way of finding an answer to this question is to ask yourself a question about readers' interests and knowledge: What would a reader have to be interested in already, and what would a reader have to know already, in order to appreciate Creedon's paper and want to respond to it?

- What would you say are some of the clearest parts of Creedon's argument? What are some of the least clear parts? Reflecting on your own aims as a research writer, what aspects of Creedon's writing style would you want to imitate in your research writing, and what aspects would you want to avoid?