I remember very clearly opening up my Notre Dame decision, and being filled with so much excitement once I had seen that I had been accepted. After my initial enthusiasm, I proceeded to read the content of the acceptance letter regarding my next steps. I scrolled all the way to the bottom of the page only to find a small, bright red text stating that, while I had been accepted, I had not met all of the requirements for admission. My excitement quickly shifted into confusion. Immediately, I contacted my regional admissions counselor to discuss what I thought must have been a mistake. None of my other schools that had accepted me said that I had not met their requirements for admission, and I was about to graduate high school, so there was no reason for me to believe that I did something wrong. She then informed me that my foreign language requirement for admission was not met, which I could eventually make up by taking two levels (equivalent to two years of high school language courses) of a Notre Dame-approved language over the summer. I had taken advanced American Sign Language (ASL) courses in high school for my high school’s foreign language requirement, and growing up in a household with two Deaf parents, I thought that ASL was recognized everywhere as a legitimate foreign language. Clearly, I was wrong.

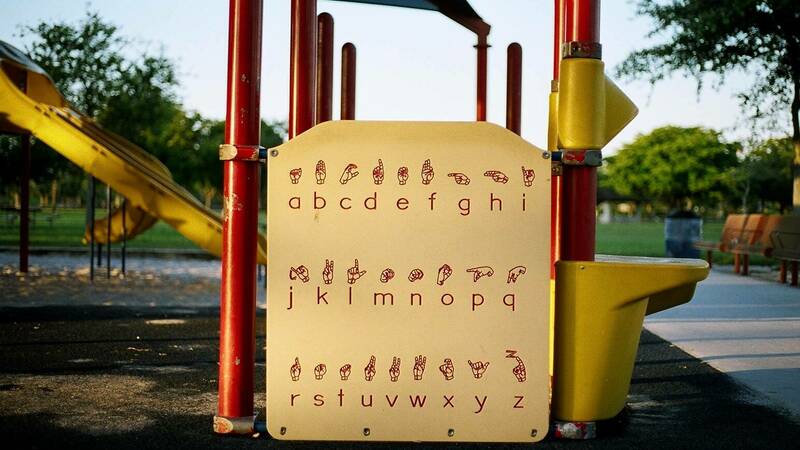

Even though I had taken ASL classes in high school, passed all of them with A’s, and am bilingual in both ASL and English, I had to take Spanish 1 and 2 over the summer because Notre Dame does not recognize ASL as sufficient to fulfill their foreign language requirements. In fact, Notre Dame is not alone. Though some universities in the United States have accepted ASL and have even created their own ASL programs to encourage students with interests in Deaf studies, many continue to disregard ASL by classifying it, as the University of Oregon does, as an illegitimate language (Pyne), arguing that it does not fit into the category of a classic foreign language and therefore is not worthy of study. Some would further argue that, because ASL is not verbally spoken, it should not be considered a language at all. But such arguments are unfounded, and ultimately demonstrate a failure of accessibility and disability rights. And, in reflecting on this issue, it is imperative to recognize that Notre Dame is not exempt from this critique. Although they have not explicitly stated their reasons for excluding ASL, the implications of this are, nevertheless, concerning. In this essay, I argue that Notre Dame should include ASL as a legitimate foreign language, both for admission and for the University’s own graduation requirements, not only because it meets all the criteria for a foreign language, but because it invites a more inclusive culture of greater accessibility at Notre Dame, which students can translate into life beyond campus perimeters.

One of the main reasons Notre Dame should accept ASL as a foreign language is the greater inclusivity it would bring to campus, benefiting both Deaf and Hearing students. In fact, the acceptance of ASL is a step that a significant number of other educational institutions have already taken. A survey conducted by Russell Rosen found that in 1991, 48 institutions of higher education accepted ASL credit for their admission requirements, which then increased to 148 universities in 2006, showcasing a growth rate of 208% (Rosen 11). There is also evidence of an exponentially increasing number of universities offering ASL classes. 1,602 students in 1990 were enrolled in at least one ASL class, and in 2002, 60,849 students were enrolled in an ASL class, a growth rate of 3,698% (Rosen 11). This apparent trend in universities accepting ASL seems to have a correlation with the growing number of high schools offering ASL courses and the resulting number of students in these courses, such that the recognition of ASL in schools is happening from the ground-up (Rosen 18). The data implies that it is inevitable that more and more high school students will take ASL to fulfill their high school’s foreign language requirement, since more schools are beginning to offer it and more colleges are beginning to accept ASL credit. By not accepting ASL for its admission or graduation requirements and failing to accommodate, Notre Dame risks excluding a growing number of prospective students, whether because they themselves are Deaf, or because, like me, they are Hearing but want to learn the ability to communicate with Deaf people.

In fact, although it is a common misconception that there are few speakers of ASL, it is one of the most commonly used languages in the United States. As Timothy Reagan notes, in 2006, to attempt to further develop ASL’s status and gain it more widespread recognition, some forty states passed legislation, using as evidence the fact that ASL is the fourth most-used language in the United States and Canada for those whose primary language is English (610). With this in mind, only a couple of the eighteen different languages that Notre Dame currently offers to meet the language requirement for graduation (“Starting Fall 2018”) are used more commonly than ASL among students whose primary language is English. This is not to propose that languages such as Russian, Swahili, and Greek should not count towards the graduation requirement, as they are completely legitimate languages and should be taught. However, evidence of ASL’s common usage and usefulness suggests that Notre Dame should be doing more in recognizing ASL’s validity as a widely used language, and it should therefore be legitimized within the institution. If state governments can recognize this, so can Notre Dame.

It is not entirely clear why Notre Dame does not accept ASL credit for its admissions and graduation foreign language requirements, but the implications of excluding ASL are still concerning. For example, on-campus institutions promoting language study, like the Center for the Study of Languages and Cultures (CSLC), provide some understanding into what the University perceives ASL to lack. It is important to acknowledge that Notre Dame seems to be open to accepting credit for languages they call “Less Commonly Taught Languages,” or LCTLs. The goal of LCTLs, as articulated on the CSLC website, is that offering LCTLs “strives to support all languages on campus, including those that do not have a home department or program” (“Less Commonly Taught Languages (LCTLs)” ). Languages in this category include Hindi, Swahili, and Quecha, which are referred to on this page as “critical languages.” “Critical languages,” as Notre Dame notes on this page, are defined as languages that can aid students who want to work in research, government positions, or “advance policies, education, or democracy” in a country that primarily speaks an LCTL. Offering LCTLs also provides students who either “grew up speaking an LCTL at home and wish to further develop their proficiency in it” or who “hope to expand their horizons by gaining proficiency in an LCTL” an opportunity to do so (“Less Commonly Taught Languages (LCTLs)”). In short, the study of an LCTL is valued as it helps students with their career goals, connect with a language that they speak at home, and broaden their intellectual “horizons.”

But ASL meets all of the above criteria. In fact, it seems like ASL could fit right in. For example, I speak ASL at home, and ASL classes have helped me and could continue to help me become more proficient in that language. In the way that the current LCTLs are approved and allow students to grow in their appreciation for the language they grew up speaking, ASL classes in high school have done the same for me, and therefore should be accepted. For example, even though I know the language, I decided to take advanced ASL classes in high school for the same reason that native Spanish speakers might take advanced levels of Spanish, or for the same reasons someone who is a native speaker of a LCTL might opt to take their language here: learning more about the roots and the conventions of a language allow you to have a deeper understanding of the language and the culture that it is associated with. Since I spoke ASL every day at home, I wanted to be able to get to know my native language in a more academically rigorous setting, rather than in a chill, home environment. I knew about the cultural customs at home, but I was unaware of the rich history that shaped ASL into the language that it is today. After taking ASL classes in high school, I learned more obscure signs that I would not use in my everyday language. And, since I use English grammar and conventions daily, I learned how to ensure that I was using ASL grammar and conventions while speaking ASL, because it can be easy to accidentally use English grammar while signing. ASL classes have refined my ASL, which is something that is not really done in a home environment, allowing me to have a greater understanding of my first language. Notre Dame could cultivate this type of academic development by authenticating the study of ASL, even if there are no specific classes or programs that support this, as with its other LCTLs.

Perhaps more importantly, ASL, like foreign LCTLs, provides value for those wishing to work in the country in which it is used; it just happens to be that, as previously noted, ASL is most commonly used in the United States, rather than in a foreign country. The potential that ASL has in this area was especially noticeable this year with the inauguration of President Biden. Historically, certified ASL interpreters have been needed for every government news conference because of ASL’s “critical” nature in government. However, accessibility has become such a priority in recent years that the Biden administration now has its own official White House ASL interpreter, reinforcing ASL’s importance within the United States government. ASL is extremely useful in all government positions, just like LCTLs have the potential to be in their countries. If Notre Dame really wants to be a campus that supports all languages, and a university that promotes the learning of LCTLs, ASL would be included in fulfilling the foreign language admission and graduation requirement.

If ASL checks all of the boxes that Notre Dame’s accepted LCTLs do, yet the University still fails to recognize it as sufficient for admission and graduation requirements, there might be more reasons and potential arguments that fuel their thinking. Perhaps, for instance, the University follows the argument that focuses on ASL’s status as a foreign language, questioning how ASL could be seen as “foreign” if it is not from another country. Because of its American background, opponents of ASL in schools say that ASL should not be considered a legitimate foreign language because Deaf culture, to some, is not a distinctive culture. This was the thinking of the University of Oregon when it was faced with the decision to allow ASL to meet foreign language requirements. When they denied the request, they stated that Deaf culture is a “subculture of American culture, rather than a foreign culture distinct from that of the U.S. in general” (Pyne). In other words, their perspective is that ASL cannot be classified as a foreign language because the language did not originate in another country, and therefore, there is no real difference of culture that results from using ASL. They also argued that, since ASL is not orally spoken, accepting ASL credit would not “allow the student to gain linguistic skills,” which is one of the core requirements of a foreign language at the University of Oregon (Pyne). Notre Dame has never outright said that their reasons behind the exclusion of ASL includes the ideas that ASL is neither foreign nor allows students to gain “linguistic skills,” and though it might be unfair to ascribe these two ideas to Notre Dame specifically, the fact that the University has not articulated their reasons for excluding ASL means both are possible, and therefore, worthy of discussion.

However, both ideas perpetuate a flawed perspective of ASL, and I would argue that they stem from misunderstanding. It is true that ASL does not originate from another country–it is a distinctly “American” language. But, this makes ASL a completely distinct language from other forms of sign language (“American Sign Language”). ASL is only used in the United States and Canada, and Deaf communities within other countries utilize their own unique sign languages separate from ASL. Still, this notion provides a lacking definition of the word “foreign.” As other universities have begun to recognize, this word has a deeper, more truthful meaning. ASL is a foreign language despite its American origins because of its “community” of others, not because of the land in which it is used. In fact, when understood as a “community,” it can be said that, for any language, “individuals not using the language of the community are considered ‘foreign’ and their language is considered a ‘foreign language’” (Rosen 12). In other words, according to Rosen, with regards to ASL, this community of users would be the Deaf community, and to those not within the Deaf community, ASL would be considered a foreign language.

In fact, the University of Oregon’s view that Deaf culture is a “subculture” of a larger culture rather than a “distinct culture” of its own reveals an inadequate understanding of the uniqueness of Deaf culture. Richard Senghas and Leila Monaghan of the Department of Anthropology/Linguistics at Sonoma State University emphasize that there is a significant distinction between Deaf/deaf, one that “highlights cultural identity as distinct from physiological deafness” (Senghas 71). In other words, “Deaf” with a capital “D” denotes those who identify with Deaf culture and customs. Similarly, “Hearing” with a capital “H” represents the culture of physically hearing people, different from that of Deaf individuals. The power that the capital “D” holds is tremendous, showing that there is a difference between physical deafness and associating oneself with Deaf culture as a result of being deaf. For example, there are many deaf people who might rely solely on hearing devices and spoken language, and because they do not use ASL and the customs associated with it, they would not identify as “Deaf,” even though they might be physically deaf.

Immersing oneself in Deaf culture comes with different customs and practices, just as in any other “distinct” culture. For instance, a common practice of Deaf people at the end of gatherings is known as the “Deaf goodbye.” Due to the tight-knit nature of the Deaf community, when an event is over and one says that they are planning to leave, it is customary for the “goodbye” to last one to two hours. Typically, a Deaf person will get up and say their goodbyes, and somehow, the goodbye turns into an extended period of socializing, conversing about something that they maybe forgot to talk about, which gradually turns into another conversation, and then another conversation, and so on. From personal experience, I have memories of going to Deaf events and dragging my parents away from their friends to the door to get them to leave. Simply put, the “Deaf goodbye” shows just one example of the “traits” and “social forms” of the Deaf community. With the knowledge that there is a completely distinct separation between the Deaf community and the Hearing community, Deaf culture cannot simply be classified as a “subculture” of American culture because that classification implies that Deaf culture does not have social behaviors, customs, and dynamics that are distinct and shared between a community of Deaf people.

Moreover, ASL is crucial for conveying many of the cultural customs that make up the Deaf community’s unique culture. As someone who was raised by two Deaf parents, and who thus speaks primarily ASL at home and grew up attending Deaf gatherings almost every month, I have seen just how different Deaf culture is from Hearing culture. There are things that are seen as acceptable in Deaf culture that are not in Hearing culture, and vice versa. For example, in Deaf culture, it is perfectly normal to be extremely blunt to the person you are talking to, whether it regards a change in their appearance or a comment of critique. As appalling as it might sound to some, my parents and their friends are extremely upfront with each other when they notice someone’s weight loss or weight gain, just to provide an example. But, ASL finds this kind of blunt expression absolutely necessary in a way that spoken language does not, as tone is conveyed in this way rather than vocally, as in spoken language. Expression is demanded in ASL, and Deaf people will not hide their feelings about someone or something through fake facial expressions or body language. In fact, my friends at Notre Dame always tell me that I am terrible at hiding how I really feel about something due to my facial expressions, simply because I was taught growing up that hiding my facial expressions was unnecessary, and, actually, counterproductive. In Hearing culture, people do not typically act as direct, and they might comment on something in an oblique way if they were to comment on something at all. Understanding ASL in the light of Deaf culture helps convey those cultural distinctions.

In these ways, then, the notion that ASL is a simple “subculture of American culture” is baseless; but so too is the notion that ASL has no linguistic foundation, and therefore cannot provide students, as the University of Oregon has argued, the opportunity to gain adequate linguistic skill. There has been significant research on signed languages to support the idea that ASL and other signed languages are “complex, grammatical system with all the core ingredients common to other human languages” (Senghas 74). The linguistic skills that a student might gain from taking Spanish or French is measurable to the skills that a student would gain from taking ASL. Grammar, specifically, is one of these skills. A common misconception is that ASL is just a signed form of English, and that ASL’s grammar is the exact same as the grammar used in English. However, this is not true. If an English speaker were to say, “I am going to the store,” the way that would be signed in ASL is “STORE I GO.” When state legislatures within the United States began to recognize ASL as a legitimate language, they took this into account, and backed up their reasoning with research done on the validity of ASL and its grammar, noting that ASL is not just a signed form of English. For example, when the Florida state legislature recognized the legitimacy of ASL in 2005, they included that ASL is a “fully developed” language with “distinct grammar, syntax, and symbols” (Reagan 610). Like other foreign languages, ASL has its own grammatical conventions; the only difference between it and other languages like French or Portuguese is that it does not require physical verbalization. ASL has a comparable grammatical complexity to that of the University’s other qualifying languages, and therefore, it should be seen by Notre Dame as sufficient for its foreign language requirements.

Moreover, it might even provide students with linguistic skills not utilized in other languages, or at least with skills that are not valued as significantly. The articulators in ASL are visible rather than audible, and because of this, students can use “three-dimensional space in complex linguistic ways,” which “gives sign languages a unique quality not shared with other languages” (Senghas 74). This is seen through the use of expressive gestures and movements, of course, but this can also be seen in the ways ASL is used to initiate conversations. Thumping a foot on the floor, slamming a hand on the table, waving a hand where their eyes can see it, or tapping someone on the shoulder is the appropriate way to get someone’s attention in Deaf culture. When I go to my Hearing friends’ houses, it is second nature for me to wave my hands or tap someone on the shoulder when I need to get their attention, even though I fully know that they would be able to hear me if I were to just say their name. It’s a linguistic feature that is unique to ASL, illustrating the distinct cultural habits of Deaf culture separate from that of Hearing culture, a difference incredibly pronounced given the ways that Hearing culture is concerned with forms of social touching. ASL provides students with the same amount of knowledge of linguistics as other languages do; they just do so in a different manner. In all honesty, to treat ASL as incapable of providing and developing linguistic skills is not simply a flawed and narrow perspective, it is, in this regard, a disrespectful one.

Taking all of this into account, Notre Dame should recognize ASL’s credibility because ASL has all of the requisite characteristics of the other foreign languages that Notre Dame currently accepts, with a rich cultural background and a strong linguistic foundation. Viewing other languages as more legitimate than ASL as if there were a ranking system of languages hinders growth as a university and, ultimately, it invalidates my first language. Other schools have begun to accept and offer ASL, and this number will continue to grow. At this point, if Notre Dame truly wants to be an inclusive university and promote being a force for the “common good,” they would acknowledge ASL as not inferior to other languages, but equal. Notre Dame must begin to accept ASL credit for all of their foreign language requirements, both admissions and graduation; eventually, though, I propose that the University should create their own ASL program with the advice of the greater Indiana Deaf community to allow students to explore their interests in this area and to encourage accessibility. This action would help the University be more inclusive and would allow students who graduate from the ASL program to enact change well beyond campus, as well as provide students the opportunity to learn about such a beautiful language and culture.

Works Cited

“American Sign Language.” National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 14 Dec. 2020, www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/american-sign-language. Accessed 31 Mar. 2021.

Andrews, Jean F., et al. Deaf Culture: Exploring Deaf Communities in the United States. United States, Plural Publishing, Incorporated, 2020.

“Evaluation Criteria.” Undergraduate Admissions, University of Notre Dame, admissions.nd.edu/apply/evaluation-criteria/. Accessed 4 Apr. 2021.

“Less Commonly Taught Languages (LCTLs).” The Center for the Study of Languages and Cultures, University of Notre Dame, cslc.nd.edu/services/lctl/. Accessed 4 Apr. 2021.

Pyne, Jessica. "Silent Language: Squabble Continues Over Sign Language at UO." Eugene Weekly, Jan 24, 2002, pp. 12. ProQuest, http://proxy.library.nd.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.library.nd.edu/newspapers/silent-language-squabble-continues-over-sign-at/docview/362761166/se-2?accountid=12874.

Reagan, Timothy. "Ideological Barriers to American Sign Language: Unpacking Linguistic Resistance." Sign Language Studies, vol. 11, no. 4, 2011, pp. 606-636,661. ProQuest, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/sls.2011.0006.

Rosen, Russell S. “American Sign Language as a Foreign Language in U.S. High Schools: State of the Art.” The Modern Language Journal, vol. 92, no. 1, 2008, pp. 10-38, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229610966_American_Sign_Language_as_a_Foreign_Language_in_US_High_Schools_State_of_the_Art.

Senghas, Richard J., and Leila Monaghan. "Signs of their Times: Deaf Communities and the Culture of Language." Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 31, 2002, pp. 69-97. ProQuest, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.020402.101302.

“Starting Fall 2018 Foreign Language Requirement.” College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame, https://al.nd.edu/advising/degree-requirements/foreign-language-requirement-students-entering-2018-or-after/.

“The History of Sign Language.” GoReact ASL Blog, 17 Nov. 2020, aslblog.goreact.com/2017/04/19/the-history-of-sign-language/. Accessed 31 Mar. 2021.