When Virginia Woolf wrote A Room of One's Own, the self-defined space symbolizes privacy, promotes equality and empowers women. Woolf may not have imagined that one hundred years later women around the world would waver over whether to demand their exclusive spaces in the public sphere. The women-only carriages have been implemented around the globe and their contested meanings are intensely discussed. They have or had been offered on some trains in Japan, India, Egypt, Iran, Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and the United Arab Emirates (Gekoski 44). The most recent case started in June 2017, when the government of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, two mega-cities in south China, created "women-only subway carriages" aimed at protecting pregnant women and young children, as well as lessening the threat of sexual assault" (Shanghaiist). This latest policy has ignited heated debates in China on whether it really protects the women or discriminates either gender. The policy met more surprising problems in practice-- just a week after being introduced, "priority carriages for women" set up on several Shenzhen subway lines have been taken over by the male commuters either ignoring or not noticing the signs. There were even more men than women in some women-only carriages, which turned out to be an irony. The lack of social consensus on this policy leads us to question: what does the women-only carriage mean in a gender culture?

Among the list of countries that have the carriages, some of them like Egypt and Iran have well-known problems with sexual assault and even violent aggression on women. Others, however, such as Japan, are not known for the obvious violence, yet strong support from either public or government is given to this special transport, which implies that it may have more to do with how people feel about sex segregation, public safety, and gender equality rather than with only the sexual risks. The public responses on this issue represent different perceptions of safety and gender as a unique cultural phenomenon worth exploring. Since the freedom of movement largely influences the employment and other activities, understanding potential meanings of this policy in a gender culture is also crucial to raising women's well-being in transportation, employment, and possibly the level of gender equality. Additionally, the case analysis of the women-only carriages in Japan can provide suggestions for the future management in China, based on the similarity between Japanese and Chinese societies.

In this research, I am studying the reality of women-only metro carriages in Japan. I will first discuss the theoretical significance of women-only carriages in combating sexual harassment, examine the history of women-only carriages in Japan, and analyze Japanese women's perceptions of those carriages in light of sociological research. Then I will focus on the particular notion of safety based on sexual segregation for Japanese women and explain the reasons behind it, with a brief reference to the contrasted case of Britain. Finally, I conclude that the contested meanings of the women-only carriages in Japanese people's perceptions as a "double-sided coin" reflect the society's gender culture.

Sexual Harassment and the Significance of Women-only Carriages

The women-only carriages are the railway or subway cars intended for women only, mostly voluntary rather than restricted. They are usually aimed to reduce sexual harassment, which is of great importance to women's freedom of movement in public spheres. The sexual assault or groping on public transport has proven damaging to women both physically and mentally. Research on sexual molestation on public transport shows that groping victimization is likely to damage victims' sense of self-control over their own environment and make them believe that they live in a dangerous world (Kirchhoff). This constructs women's fear of crime victimization greater than men's. Consequently, greater fear of crime discourages women from using public transport, therefore, restricting women's movement in this sector and also workspace. Women-only transport can not only give women a sense of safety but also empower them to travel in the public space and participate in public affairs, including work, school, and social activities (Horii and Burgess 43). This sense of safety will possibly result in improving women's internal locus of control, which means that they will feel that they have more control on the outcomes of the events in their lives (Rotter).

The present findings suggest that stranger harassment is a remarkably common occurrence for many women, and that common means of coping with it may lead to increased self-objectification. Since self-objectification has negative consequences for women (e.g., depression and eating disorders), stranger harassment is a serious form of discrimination (Fairchild, K. & Rudman 1). In contrast, the freedom of public transport mobility will possibly give women access to more economic and educational opportunities, while improving their mental health conditions.

The History of Women-only Carriages in Japan

The history of women-only carriages in Japan has been studied in great detail by Horii and Burgess in Constructing sexual risk: 'Chikan', collapsing male authority and the emergence of women-only train carriages in Japan:

"In late 2000, women-only carriages (women-only train carriages) were introduced on late night services in Tokyo by the Keio Railway Company in response to men groping female passengers. Other train operators followed Keio's gender segregation initiative. In 2001, the West Japan Railway in Osaka became the first to offer them during the morning rush hour and the Hankyu Railway became the first to run them all day. Train operators in other major cities followed and by 2005 most Tokyo operators, including the subway system, followed suit. Women-only train carriages are typically located at the end of the train, which may require women to walk the length of the train, along a busy platform, in order to use them. Women-only train carriages are not available on all trains and at all times, however, and segregation remains ultimately voluntary. Women do not have to use them, while no legal sanction can be given to men who enter women-only carriages. (Horii and Burgess 42)"

As Horii and Burgess pointed out, the women-only carriages in Japan were introduced by some private railway companies concerning the problem of groping (or the Japanese translation of gropers, Chikan) which has been a notable phenomenon on Japanese commuter trains and subways since the 1990s, especially for young women. According to the Gender Equality Bureau's survey (2000), 48.7% of Japanese women over 20 years old had at least one experience of being groped. The intense debate over mass media resulted in the launch of the carriages by the railway and subway companies.

The practice received mixed responses from the public. Some women have reported feeling safer and men have welcomed not having to worry about false allegations of assault (Joyce). What a woman passenger told ABC News might be a representative opinion, "because it's just only girls, females, and we don't touch, you know, so … [it's] very safe!" (ABC) Statistics show that the number of reported cases of groping and other lewd behaviors including secretly taking photos of women declined in Tokyo from 2,201 cases in 2004 to 2,137 in 2005, a fall of 3 percent (Chockalingam and Vijaya 172). Since most groping cases occur in the trains or subway, this could be evidence that the introduction of this special carriage has helped to combat sexual assault. However, despite the advantages the carriages brought for many women, there were also voices against them. Some men protested that the system discriminated against men, since they paid the same fare but were packed as Sardines and even labeled as "evil people" while ladies rode in comfort (Emi Doi 1).

Women's perceptions of women-only carriages in Japan: A Double-Sided Coin

While the current quantitative study on this topic remains limited, the sociological research by Horii and Burgess mentioned above has major significance in analyzing the social trends revealed by Japanese women's attitudes towards women-only carriages. In this section, I will analyze their research as well as combine other evidence to illustrate women's perceptions of women-only carriages in Japan. According to my findings, the women's perceptions of them can be understood as a "double-sided coin": on one side, it ensures safety and hygiene, challenges the "salarymen masculinity" and liberates women from gazing; on the other side, it still symbolizes female vulnerability.

In August 2007, 155 young women in their 20s completed the survey at a variety of locations in central Tokyo. The survey involved face-to-face interviews of questions related to the issue of women-only carriages (Horii and Burgess 45-50). Notably, survey responses showed a wide discrepancy between high supports for the idea of women-only carriages but much more limited actual usage. Over half (54%) of the 155 Japanese women interviewed would like to see more women-only carriages, but only a minority of 7% women actually used women-only carriages "very often." This was often due to unavailability of services, and long walks to women-only carriages situated at the end of trains. The concerns over personal feelings of safety, not limited to groping, dominated the survey responses as well as newspaper reports on women's opinions, including the terms like "feeling safe," "feeling at ease" and "safety." Comments also highlighted female "cleanliness" and complaints about the physical unhygienic presence of oyaji (a term with multiple meanings, here referring to white-collar, middle-aged men, or "salarymen").

In the analysis, Horii and Burgess classified the respondents into four categories in relation to their approval and use of women-only train carriages: approving users (20.6%), approving nonusers (33.5%), disapproving nonusers (29.7%) and disapproving users (11.6%). For the approving users, sexual segregation from men provided a greater sense of safety and even empowerment. They commented that a further expansion of the service would provide women with a safer public transport environment. Other two supporting reasons include the pragmatism of more comfortable and spacious transport experiences, and the hygienic environment without men's sweaty smell and physical proximity to elder men. The "female cleanness" was felt to provide these approving users with a sense of security, while the presence of unhygienic men constructed a sense of vulnerability.

The approving nonusers were the largest of the four groups. Their supporting reasons are mainly the same as the approving users. A majority of them explain their non-use by complaining of a lack of availability of women-only carriages in time and space. The disapproving nonusers, in contrast, rejected the idea of women-only carriages based on their strong individualism and optimistic bias. They saw the problem of groping as something which each woman should deal with personally on the basis of "self-responsibility." Some questioned the effectiveness of the carriages because that might force women away from mixed-sex carriages. In general, they were against the notion of segregation based on the view that it undermines gender equality. This identifies with the dominating opinion of British women which will be discussed in the next section.

A significant finding of the survey was the symbolic rejection of "salarymen" masculinity in the supporters' responses. I summarize that the rejection is specifically against three symbolic meanings of salarymen (or oyaji): the sexual danger (Chikan), unhygienic features and traditional patriarchal authority in Japanese society. First, the discourse of hygiene and disgust against oyaji justified the existence and use of women-only carriages. Oyaji in this specific context refers to a derogatory term which denotes "unattractive, unhygienic middle-aged men" associated with "salarymen masculinity." Interestingly, the notion of "female cleanness" appeared so frequently in the responses that it became almost equal to the notion of safety. Among the respondents, a variety of negative associations are made with men, including drunkenness. Ten respondents even explicitly identified "oyaji" as the problem, claiming them as unhygienic, smelly, "dirty" and a source of "pollution." What's more, "the representation of oyaji as salarymen has also been established as the stereotypical image of Chikan, the groper" (Horii and Burgess 51). As statistics on one of the largest circulated newspapers, Yomiuri suggests, men in the 30s and 40s are the two largest groups of gropers between 1997 and 2008 (Yomiuri). Their images often constructed the sexual threats to the women, which incites the feelings of the anxiety and disgust. However, in the responses, the mention of "personal safety" is not limited to the practical physical safety away from groping. It is more properly understood as a sense of safety and relief to have one's own space away from the whole salarymen's "aura." The unhygienic impression, sexual dangers and their invisible oppression on women often intertwine in this undesirable aura. In this context, young women's expression of repulsion to their physical presence can be regarded as against the hegemonic masculinity and their objectification of women.

As Horii and Burgess illustrate, the targeting of salarymen, oyaji, as likely sexual criminals and undesirable presences may be associated with their dramatic decline in status and authority. When oyaji denotes salarymen, it embodies Japan's economic success of the 1950s and 1960s until 1980s. In those times, the white-collar salarymen were the backbone of economic growth and became the hegemonic model of masculinity (Steger). By 1989, however, Japan entered a recession that intensified into 1990s, turning the salarymen from the breadwinners of families and pillars of society to the symbols of economic recession and bankruptcy. Suicide rates have risen considerably since around 2000, particularly among middle-aged men, often because of job loss, financial problems, and the consequent threat to their identity as responsible members of society (Steger). Meanwhile, the Japanese women began to question the common sense of gendered division of social roles, and to seek more active social and economic positions. Many of them doubted if marriages were compatible with their preferred lifestyles, which resulted in a decreasing birth rate. Due to the salarymen's falling position and the rise of women's participation in economic and social life, the younger generation began to question oyaji's authority and challenge the patriarchal order. In the public discourse amongst some young women, the meaning of oyaji even changed without denoting ordinary white-collar, middle-aged salarymen. Instead, it means "dirty/unhygienic," "male-dominated," "disorganized," "overconfident" and so on (Sonoda). Overall, everything negative about the patriarchal order is oyaji. Obviously, it can be a kind of women's negative stereotype towards the men, which is not constructive for gender relations. However, it also symbolizes an implicit desire of the young women to resist Japanese patriarchy.

Another sociological research Negotiating Gendered Space on Japanese Commuter Trains by Cambridge scholar Steger confirmed this contested gender relation by focusing on a particular phenomenon: "gazing." According to the research, "an important way in which public space is managed is through the gaze, which can invade other people's space but can also protect one's space from the gaze of others (Steger)." The "territories of the self" (Goffman) can be invaded by touch, gaze, sound, and smell (Horii). In the context of mixed commuter train carriages, men are usually the "looking subject", whereas women are the "object of the gaze." The demands on women, especially young women, for decency and decorum are much higher than for men. For example, gazing happens with napping, another widely noted phenomenon on Japanese commuter trains. While so many people fall asleep on the trains, the observed objects are often women rather than men. "Women, as the gender that is looked at, are required to display appropriate conduct—that is why they are expected to keep their legs neatly together and their hair well-groomed. (Steger)" A vast majority of mass media criticized the sleeping women passengers with "hair loose and legs wide apart," because those are not decent postures according to traditional etiquette, even considered signs of sexual energy. Therefore, most women have to take care to sleep with their legs together and in a relatively stable upright position. In contrast, men have few inhibitions and do not need to fear criticism if they keep their legs open, snore or have any unmannerly postures.

In fact, "gazing" is directed towards not only the napping women passengers, but almost all of them. In the early twentieth century, secretly watching young women during their commute became a popular topic in the predominantly male literature (Steger). Nowadays, women still need to keep their postures in control not to signal the "disorderness" or "indecency" which are defined by the onlooker: usually male. Protest to women putting makeup on trains is another example of the restraining effect of gazing on female passengers. Remarkably, after noisy and pushy people, observing a woman doing her make-up ranks second highest among things that make people feel uncomfortable on trains. Tokyo Corporation, a private railway company, even produced a highly controversial advertisement calling women putting makeup on trains "ugly". Most young women who did makeup could not understand why they are criticized, while the protesters expressed the feeling of being ignored or disturbed. According to Steger's interpretation, when women put on makeup on the trains, some men around will feel that there is no one making herself look attractive for them; they were simply irrelevant fellow passengers. At the same time women are made the objects of gazing, by ignoring criticisms, they take the power to define the tertiary space. "Hatene," one of the bloggers, supports this view by stating the girls putting on makeup as conquering the space and challenging the male's social authority. I also had an alternative interpretation: according to the sociologist Goffman's symbolic interaction theory, interactions are divided into front stage and backstage (Goffman). Since men are used to viewing women's makeup as backstage preparation, they cannot accept it as a front stage performance that almost treats them as non-persons. However, criticizing or banning this autonomous act of women seems an excessive intervention which invades their spaces by gazing and judging.

Drawing from Horii and Steger's research, I conclude that women's repulsion to "gazing" probably contributes to the rise of women-only carriages. A number of women say that they feel safe and more comfortable away from the male gaze in women-only carriages, suggesting that the "male presence demands behavioral regulation and control, and its absence is experienced as liberating (Steger)." Respondents also complain about the oyaji smell brought by the physical presence of men (Horii 49). In contrast, reports show that women are pleasant to have the freedom of doing makeup, napping or knitting as they like in women-only carriages. One woman recounts the camaraderie of the women-only car, where make-up can be applied without concern for one's neighbors, saying that "I'd rather have this choice. It's better than having my face in the armpit of some smelly man all the way into work (Financial Times)." As we think of Michael Foucault's findings "the constraining, almost compulsive gaze men cast at female bodies is always bound up in a complex of power and knowledge (quoted in Löw 2006:127)," the constraints on female behaviors following gazing on commuter trains subtly mirror the existing gender inequality. The desire to define one's space freely without gazing and male presence can be identified as an important reason for supporting women-only carriages.

In conclusion, the perception of the women-only carriage among women passengers can be interpreted as a "double-sided coin." On one side, it provides a sense of safety and even empowerment for women in multiple ways. It protects them from the sexual threats of groping and ensures an environment of "female cleanness". More subtly, the support for women-only carriages symbolizes a rejection specifically against the masculine power and social authority represented by salarymen (or oyaji). While salarymen are favored long in the Japanese history as the pillars of economic stability, now the young women are demanding more public space to act freely. The liberation from gazing, especially for young women napping or doing makeup, may be an approving reason for the women-only carriages. On the other side, the existence of the carriages still symbolizes the female vulnerability. "When female vulnerability is perceived as a norm, sex segregation can be regarded positively (Horii and Burgess 52)." Some women, in the sense of self-control and individualism, rejected this choice because they feel that women can and should feel safe in the mixed carriages. After all, men and women inevitably interact in public spaces. It is still doubtful whether the temporary absence of masculinity can be a kind of female empowerment. The intertwining of the two perceptions possibly accounts for the increasing trend of "approval but non-use" among women passengers.

The Notion of Safety for Japanese Women

A notable notion in Japanese women supporters' perceptions of women-only carriages is that sexual segregation from men can provide a sense of safety and even empowerment (Horii and Burgess 46). This notion draws a sharp contrast with the ideas of British women who were once offered the similar option. In August 2015, the British Labour leadership candidate Jeremy Corbyn claimed that he would consult on the option of introducing women-only carriages to help reduce sexual harassment, which received intense criticisms in the public forum, especially from the women. Women critics considered this proposal insulting to both men and women, arguing that it put the onus on the latter to avoid predators, while also exaggerating the threat that men pose (Independent). There is even an analogy that "we don't try to tackle rising racial hate crime by segregating black people" (The Guardian). Concerning safety in particular, British women feel that they do not necessarily trust all the women, and a segregated section could positively attract attention to women travelling alone (Lynch and Atkins); men can actually be comrades and offer help when they meet dangers (Times). As a result, August 2017, Corbyn dismissed his own suggestion by saying that "people do not want it." (The Telegraph) Both economically developed countries with very similar rates of women participation in the labor force (Brinton 433), Japanese and British women showed considerably different attitudes towards the proposal which were partly based on different values of safety. The history, the lack of positive solutions and the low level of self-efficacy are three possible reasons that account for the Japanese women's tendency for segregated carriages.

Historically, Japanese society has a Confucian tradition that embraces the patriarchal values. It is only after the 19th Century Meiji Restoration that women began to acquire active positions in the society other than daughters and wives. After World War II the Americans brought many reforms to Japan. MacArthur spoke of the "essential equality" of the sexes, giving impetus to women's suffrage which came in 1946. All inequalities in laws were ended, and more and more colleges became open to women. However, the current generation is still inevitably trapped by the past values that emphasize men as the supreme sex. While women in Japan are now among the highest in the health, survival and education globally, there is still a wide gap in political empowerment and economic working authority. In the 2012 Global Gender Gap Report, Britain ranks 18 in the global gender equality while Japan ranks 101 (Global Gender Gap Report). In addition, several contemporary critics on the major newspaper Japan Times identified the female objectification as a domestic problem, including the stereotypical images of women as cute and vulnerable (The Japan Times). That may contribute to the notion of segregation as protection.

The second reason is that Japan lacks other positive solutions to the groping problem in replacement of the women-only carriage, including the long-time sexual assault reporting system and education. In comparison, Britain has two significant programs that encouraged the women's reports of sexual assaults: Project Guardian and Everyday Sexism Project. Project guardian is a joint initiative among London's public transport systems and the city police. The police created a confidential hotline and text-messaging service, used social media to raise awareness and encourage reporting, and collaborated with researchers in evaluating the effectiveness of global measures to combat sexual assault. They also staged several "weeks of action", involving increased patrolling of public transport by both uniformed and plain-clothed police officers, several of which resulted in multiple arrests (Bates). In August 2014, the BTP recorded a 21% increase in sex offence reports, a rise which was attributed partially to increasing reporting as result of Project Guardian (BBC). Everyday Sexism Project, a website that documents everyday examples of sexism experienced by contributors all over the world is founded in April 2012 by English journalist Laura Bates after being sexually harassed on London public transport. It has spread to 25 countries, raised awareness globally and advised the Project Guardian police officers in how to respond to women's reports of sexual offences (The Guardian). Since increased reports may help the police handle and reduce sexual assault, the collaboration between the police department and the NGO is a praiseworthy effort to improve the safety environment of women.

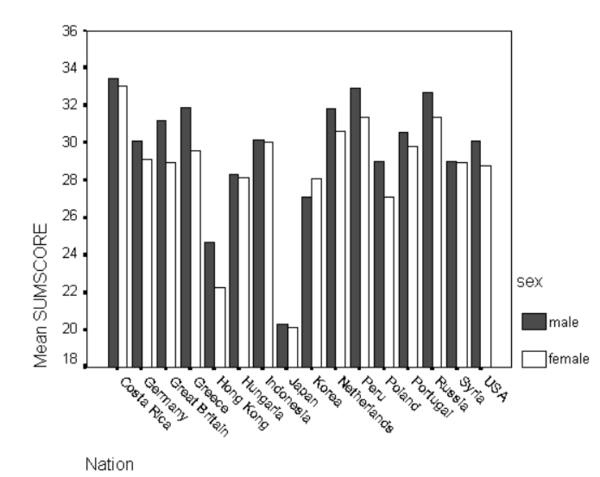

The third hypothetical reason stems from a socio-psychological perspective. Low level of national self-efficacy among Japanese people may lead to their dependence on institutional structures like segregated carriages when dealing with sexual assault problems. The term "self-efficacy" refers to personal action control or agency. It reflects the belief of being able to control challenging environmental demands by means of taking adaptive action. General self-efficacy aims at a broad and stable sense of personal competence to deal effectively with a variety of stressful situations. As shown in figure 1 below, a cross-cultural sociological research on self-efficacy among 22 countries demonstrates that Japanese male and female have the lowest score (Schwarzer). In this context, lower self-efficacy may make Japanese people prefer institutional forces like the segregated carriages to individual challenges to the underlying problem. Consequently, the effectiveness of the women-only carriages would probably perpetuate women's reliance on them and prevent them from seeking other solutions, which may become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Conclusion

As the research investigated, groping on public transportation leads to serious mental problems for victims, and increasing fear will discourage women from participating in public affairs. The women-only carriages, implemented in Japan as a solution to groping, however, have complicated implications in gender culture. Women's perceptions of the carriages can be understood as a "double-sided coin": on one side, it ensures safety and hygiene, challenges salarymen's masculinity and liberates women from gazing; on the other side, it still symbolizes female vulnerability. Women's notion of safety based on sexual segregation possibly results from the historical gender gap, the lack of positive solutions like effective crime reporting systems and the low level of self-efficacy in their national culture. Interestingly, according to a recent survey, the majority of men and women in Japan both supported the proposal of men-only carriages, which embodied a similar notion of segregation prevalent among Japanese men.

While there is evidence that women-only carriages do lead to the reduction of sexual assault, in societies with more progressive values on gender equality like Britain, where feminism originated, the segregated transport would probably be regarded as a retrograde step which lacks imaginative thinking in solving the problem. Overall, my research has implications for the management of women-only carriages in certain cultures. Further quantitative sociological research on women-only transports needs to be done to evaluate their effects accurately and provide suggestions for other countries. Meanwhile, currently, this policy still seems a short-term fix that will not address the underlying deeper problems of sexual harassment and public security. It can even convey the negative message that women have to be segregated in order to be protected from sexual threats. In other words, "a carriage of women's own" draws a spatial boundary that may reinforce the mental inequality of genders. Even if women-only carriages are a positive temporary step in some regions, it is essential for society as a whole to make joint efforts to improve gender equality and public security environments, so that all genders can feel empowered to travel freely beyond limits.

Works Cited

Berry, J.W., Poortinga, Y.H., Segall, M.H., Dasen, P.R. (1992). Cross-cultural Psychology: Research and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521- 37761-7.

Bates, Laura (1 October 2013). "Project Guardian: making public transport safer for women". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

Brinton, Mary C. Women and the economic miracle: gender and work in postwar Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Berry, J.W., Poortinga, Y.H., Segall, M.H., Dasen, P.R. (1992). Cross-cultural Psychology: Research and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521- 37761-7.

Emi Doi, Women-Only Cars on Commuter Trains Cause Controversy in Japan, web.archive.org/web/20071218143817/www.truthout.org/cgi- bin/artman/exec/view.cgi/35/11500#.

Fairchild, K. & Rudman, L.A. Everyday Stranger Harassment and Women's Objectification. Soc Just Res (2008) 21: 338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0073-0.

"Female objectification and gender gap in Japan." The Japan Times, www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2016/07/24/commentary/japan-commentary/female- objectification-gender-gap-japan/#.WfiC0NWnHIV.

Goffman, Erving, 1971. Relations in Public. Microstudies of the Public Order. New York: Basic Books.

Gekoski, A., Gray, J.M., Horvath, M.A.H., Edwards, S., Emirali, A. & Adler, J. R. (2015). "'What Works' in Reducing Sexual Harassment and Sexual Offences on Public Transport Nationally and Internationally: A Rapid Evidence Assessment." London: British Transport Police and Department for Transport.

Horii, Mitsutoshi; Burgess, Adam. "Constructing sexual risk: 'Chikan', collapsing male authority and the emergence of women-only train carriages in Japan." Health, Risk & Society. 14, 1, 41-55, Feb. 2012. ISSN: 13698575.

Horii Mitsutoshi. 2009. Josei senyō sharyō no shakaigaku [Sociology of the women-only train]. Tōkyō: Shūmei Shuppankai.

Joyce, C. (2005, May 15). Persistent gropers force Japan to introduce women-only carriages.

The Telegraph [online]. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/japan/1490059/Persistentgropers-force-Japan-to-introduce-women-only-carriages.html

K. Chockalingam & Annie Vijaya, 2008, Sexual Harassment of Women in Public Transport in

Chennai City - A Victimology Perspective, THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY & CRIMINALISTICS, NO. 3, SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER, 2008.

Kirchhoff, C.F., et al., 2007. The Asian passengers' safety study of sexual molestation on trainand buses: The Indonesian study. Acta Criminologica, 20 (4), 1–13.

Löw, Martina. The Social Construction of Space and Gender. European Journal of Women's Studies Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi), 1350-5068 Vol. 13(2): 119–133; http://ejw.sagepub.com DOI: 10.1177/1350506806062751

News, ABC. "Japan Tries Women-Only Train Cars to Stop Groping." ABC News, ABC News Network, 10 June 2005, abcnews.go.com/GMA/International/story?id=803965.

Reporters, Telegraph. "Jeremy Corbyn says no to women-Only carriages on trains because people don't want them." The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 25 Aug. 2017, www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/08/24/jeremy-corbyn-says-no-women-only-carriages- trains-people-dont/.

"Railways sex offences rise by 21%". BBC News. BBC. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014

Shanghaiist in News on Jun 27, 2017 5:55 pm. "Shenzhen rolls out new 'women-Only' subway carriages, igniting debate over gender segregation." Shanghaiist, 27 June 2017, shanghaiist.com/2017/06/27/women-only-metro.php.

Steger, Brigitte, "Negotiating Gendered Space on Japanese Commuter Trains," University of Cambridge, Volume 13, Issue 3 (Article 19 in 2013). First published in ejcjs on 6 October 2013.

Schwarzer, Ralf & Scholz, Urte, 2000, CROSS-CULTURAL ASSESSMENT OF COPING RESOURCES: THE GENERAL PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY SCALE, userpage.fu- berlin.de/gesund/publicat/world_data.htm.

"The Global Gender Gap Report 2017." World Economic Forum, www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2017.

"Women-only carriages: the global view." 2016, Financial Times, www.ft.com/content/8cd1a9d4- 4bf0-11e5-b558-8a9722977189.

Yomiuri, reported ages of men accused of 'chikan' in Yomiouri Shinbun newspaper between 1998 and 2007. Source: Yomiuri Database (http://www.nifty.com/yomidas/)